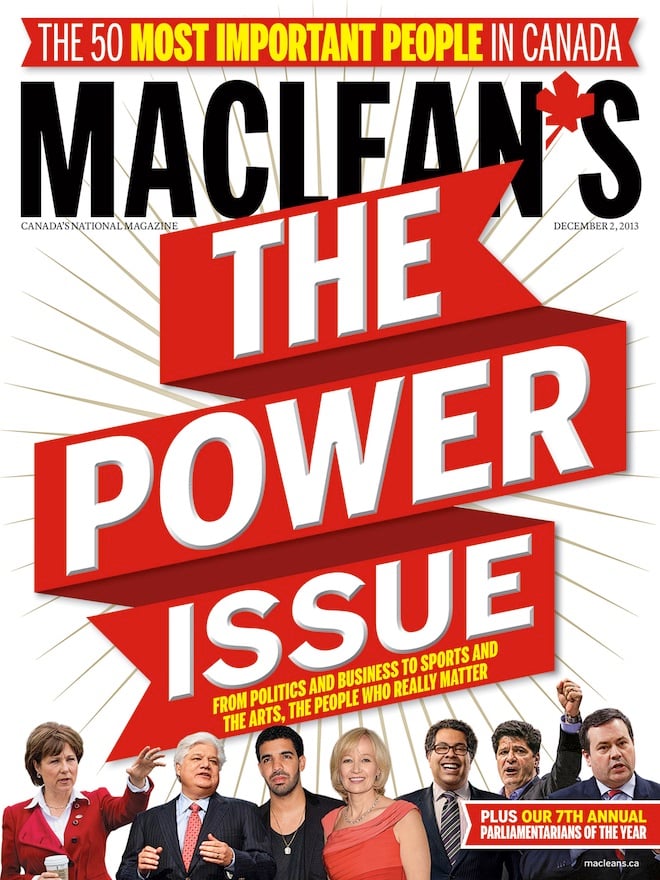

Defining power is almost as hard as acquiring and keeping it. Being able to command the spotlight is often an attribute of the powerful, but so too is a knack for operating from the shadows. We tend to closely associate wealth and power, but it would be foolish—and boring—to ignore the clout of those whose paycheques wouldn’t be all that impressive, whether public servant or priest, creative thinker or cultural arbiter. Presiding over the pinnacle of a hierarchy might seem like the common condition of the powerful, until someone inevitably mentions one of those intriguingly influential loners, iconoclasts or introverts.

Keeping all these intriguing contradictions and counterbalances in mind, writers and editors at Maclean’s who cover the Canadian scene compiled the Power List with three broad concepts in mind: institutional clout, capacity for innovation and timeliness. Viewing the 50 fascinating individuals who made our final cut through these three lenses is the best way to impose some order in what might appear to be a dizzyingly diverse bunch. Beside each name, you’ll see three icons.

This symbol indicates our assessment of the individual’s institutional standing. For instance, the Prime Minister scores the maximum five because he runs the whole federal government. On the other hand, we were intrigued by a certain creative marketing mind. But, hey, an ad agency isn’t an establishment corporation or a sprawling public sector institution, so he ranks just one blue pillar icon.

This tells you how much weight we assign to a given individual based on the inescapable fact that were compiling this list in late 2013 with a weather eye to 2014. Power must have events through which to express itself. Thus, individuals associated with the upcoming Winter Olympics in Russia rank five clocks—and probably wouldn’t make next year’s list at all. By contrast, a banking watchdog rates just two, although we’ll wish we’d assigned more if, heaven forbid, another financial crisis hits anytime soon.

Power, in the broadest and perhaps best sense, often flows from ideas. The guy who’s taking a serious shot at making quantum physics make money? We assign him the full five. But a prime-ministerial aide whose undeniable power comes from loyalty to the boss and longevity in high places? Just one.

You disagree? We also claim there’s power in the ability to start an argument. JOHN GEDDES

2013’s Power List

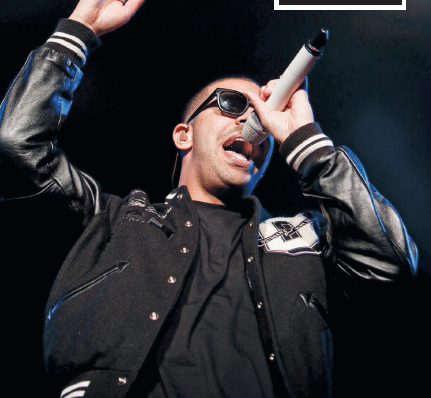

| 01. Stephen Harper 02. Nenshi 03. Dias 04. Wiseman 05. Charbonneau 06. Novak 07. Weston Jr. 08. Trudeau 09. Dickson 10. Laziridis | 11. Butts 12. McLachlin 13. Mulcair 14. Moore 15. Clark 16. Peladeau 17. Laureen Harper 18. Kenney 19. Pourbaix 20. Byrne | 21. Caira 22. Yzerman 23. Conway 24. Merklinger 25. McCartney 26. Fortier 27. Flaherty 28. Poilievre 29. Manning 30. Lisée | 31. Redford 32. Poloz 33. Ferguson 34. Blais 35. Oliver 36. Jenkins 37. Lawson 38. Ouellet 39. Atleo 40. Keller | 41. Keesmaat 42. Ghomeshi 43. Drake 44. Brabant 45. Southern 46. Gomes 47. Chow 48. McCaughey 49. Edwards 50. Bronfman |

01: Stephen Harper

Power under pressure

Even wheeling his arms like a cartoon character executing an endless pratfall, Stephen Harper still controls the fates of so many other figures in Ottawa that he remains kingpin. He shuffled his cabinet, ending the ministerial careers of Vic Toews, Ted Menzies, Diane Ablonczy and Peter Kent. He flew to Brussels the day after the Throne Speech and clinched a trade deal with Europe. In Calgary, meeting wary delegates at the Conservative party convention, he said little about the Senate expense scandal that has all but ruined his 2013 and cost him a trusted confidant, his former chief of staff Nigel Wright. What he did say sounded for all the world like a decision to abandon any ambition for serious Senate reform. Instead he listed his government’s accomplishments—the end of the long-gun registry and the Wheat Board monopoly; a plan for free choice in cable-TV channel selection—that should ensure his base stays loyal.

Even wheeling his arms like a cartoon character executing an endless pratfall, Stephen Harper still controls the fates of so many other figures in Ottawa that he remains kingpin. He shuffled his cabinet, ending the ministerial careers of Vic Toews, Ted Menzies, Diane Ablonczy and Peter Kent. He flew to Brussels the day after the Throne Speech and clinched a trade deal with Europe. In Calgary, meeting wary delegates at the Conservative party convention, he said little about the Senate expense scandal that has all but ruined his 2013 and cost him a trusted confidant, his former chief of staff Nigel Wright. What he did say sounded for all the world like a decision to abandon any ambition for serious Senate reform. Instead he listed his government’s accomplishments—the end of the long-gun registry and the Wheat Board monopoly; a plan for free choice in cable-TV channel selection—that should ensure his base stays loyal.

Sure, the Senate scandals and his inability to get a Keystone XL decision out of Barack Obama robbed his post-2011 majority mandate of grace. In front of him in the House he faces Tom Mulcair and Justin Trudeau, two different kinds of formidable competition. But he has assets, foremost being a relatively strong economy. His finance minister, Jim Flaherty, promises a balanced budget by 2015. That would allow Harper to promise billions in tax cuts. Trudeau and Mulcair will argue for a busier federal government; Harper will run on the price of his rivals’ ambitions. Fronting a saloon band in Calgary after his convention speech, Harper sang a string of old hits. One of them was Takin’ Care of Business by BTO. Harper’s business is winning, and he does not intend to stop doing that just yet. PAUL WELLS

02: Naheed Nenshi

Like he can walk on water

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

|

When Naheed Nenshi’s name comes up, Torontonians have only one question: When is he coming to save us? When Calgary’s charming, straight-shooting progressive mayor visits Toronto now, he is greeted with an affection that borders on the riotous. Even fairly conservative Torontonians seem to feel that the Toronto-born Nenshi somehow must have been misplaced or distracted on his natural path to leadership of their city. “We don’t need him full-time,” pleads Kelly McParland on the National Post’s website. “One week a month should do it.”

Albertans laugh about this—even the ones who do not like Nenshi have to laugh. But there is a certain validity to Torontonians’ feelings that they could have had Nenshi to themselves if history had panned out just a little differently. “I spent most of my 20s based in Toronto,” the newly re-elected mayor notes as he prepares to dart back briefly into the city of his birth for a conference.

After Nenshi finished his master’s degree from Harvard in public policy, he worked for McKinsey, the somewhat cult-like international business consultancy that recruits high-IQ graduates to visit institutions, study them for a few weeks, and tell them what they’re doing wrong. Being at McKinsey is a bit like special-forces training for business leadership—but you can also learn a lot about non-profits and government agencies, if that is where your heart lies. Pretty soon Nenshi had graduated from the cult, as its young associates are expected to, and was doing his own consulting work for retailers and bankers.

But the gravitational effects of family kept pulling Nenshi back to Calgary, where he had grown up and where his parents and his sister were still entrenched. He moved back into Cowtown almost on a whim in the autumn of 2001, turning his Toronto apartment over to a cousin and having his personal effects shipped to his parents’ basement. He quickly became embroiled in a controversy over the proposed privatization of the city’s power interests, and he spent the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, in an extremely awkward public hearing at City Hall, choosing to attend because no one seemed to know whether it ought to be cancelled. “The news on TV was too terrifying to contemplate anyway,” he recalls. “Everybody was so shell-shocked.”

Sept. 11 brought on “a period of underemployment” for Nenshi as his jet-setting consulting work dwindled temporarily. Before long he was back in the game, at one point working for the UN and spending three weeks out of every four in New York City. “Eventually my father got really sick and I got one of those ‘You’d better come home right now’ phone calls,” Nenshi says. “And I decided it was better to be actually rooted in a place—that I wanted to be part of Calgary for good. That’s when it really stuck.”

That’s not good news for anyone hoping for Nenshi to burst out of Calgary onto the national scene. The government of Calgary has just switched to four-year terms for its mayor and council, and Nenshi’s re-election campaign was dogged by rumours that he may turn his sights elsewhere before he completes a second stint. He has always denied them flatly. Such denials don’t normally carry much weight, but Nenshi speaks with surprising passion of municipal government, just as Peter Lougheed, another much-solicited national saviour figure from Calgary, once praised provincial government as the most fulfilling field of political activity.

“I always say that if the federal government just disappeared while we were talking, it would probably take you a couple of weeks to really notice,” Nenshi observes. “If the provincial government disappeared, you would need a few hours, maybe a day, to become aware of it unless you were in school or in a hospital. But if the municipal government disappeared, there go the traffic lights, the water, the electricity, the gas . . . you would, frankly, notice pretty quickly because you might be dead.”

Maybe Nenshi’s innermost ambitions do run higher than Calgary City Hall. It’s worth remembering, though, that he is keen on making City Hall itself much more powerful. Along with the city of Edmonton, Calgary is close to a deal with the province on a pair of “city charters” that would devolve more responsibilities explicitly onto the municipal governments along with a slice of tax revenue. Both cities have ambitious multi-decade transit plans and have pretty much tapped out their own property tax base covering operating costs.

Nenshi and others have spitballed giving the big cities their own earmarked taxes. He is downplaying that concept for now, but there is an urban consciousness-raising under way in Alberta. Demographic change is threatening the great tradition of hinterland Alberta playing the cities against one another, keeping them in a state of constant uproar over which one is daddy’s favourite. Albertans who live and pay their taxes downtown are starting to realize that having municipal governments for both small towns and counties is one of history’s greatest jobs-for-the-boys scams. There is an awareness that Alberta cities have been abused for a long time on highway spending, industrial taxation and health budgets.

Rebalancing the Alberta treasury is worthy of Naheed Nenshi’s attention, and it requires the kind of public-policy training he has, but if he were to depart for a different scene too early it might all come to naught.

Moreover, it is surprisingly hard to specify a concrete scenario for a next political step. Nenshi’s chief of staff and close confidant Chima Nkemdirim helped found the Alberta Party as a vaguely progressive alternative in provincial politics, but so far it has been a flop. Nkemdirim is rumoured to be eyeing one of the downtown federal Liberal nominations, but it is hard to imagine Nenshi personally giving up the comfortable mayor’s chair to carry a battle standard for Justin Trudeau. The previous two Calgary mayors were both popular Liberals who were constantly rumoured to be on the verge of bolting, but when they tired of the gig, well, it turned out there were much easier ways to have a nice life in Calgary than running against Conservatives there.

Anyway, he is still having enormous fun as a mayor, or at least that is the overwhelming impression he gives in conversation. Asked about frontline services, he goes on a gleeful 10-minute tangent about putting GPS units on the city’s snowplows. “We created a website that shows in real time, after a snowstorm, which streets have been plowed and which ones are being plowed,” he says. “It sounds like feel-good window dressing, but it became the most-visited page on the city’s website awfully quickly. The ability to check road conditions before you leave the house turns out to have a discernible safety impact, and there’s a cost saving in phone calls and complaints. If you’re mad and you want to know where the snowplows are, you can literally go look.” He does this a lot himself, he adds.

Nenshi’s re-election campaign turned a bit ugly when it became public knowledge that real estate developers were organizing against him. He has been berated as a “socialist” because he is reluctant to let new insta-neighbourhoods keep hooking up to Calgary’s service grid—at Calgary’s expense—until they stretch to the outskirts of Butte, Mont. Note, however, that his long-standing position on the eternal “secondary suites” fight that sometimes dominates Calgary headlines is the libertarian one. He wants to relax zoning rules so homeowners with spare room can rent to new-arriving workers who don’t need much; this would, as a side effect, bring thousands of existing illegal suites back under landlord-tenant law. If this is socialism, it’s a curiously Cato Institute-friendly species of it.

Nenshi may or may not be the most popular individual politician in Canada right now—is there another candidate?—but the developers’ campaign against Nenshi-friendly councillors was not totally ineffective, and the balance of power on council remains about as even as it was before October’s vote. The mayor has explicitly put his secondary-suite crusade in abeyance while the new council continues to deal with the aftermath of the spring floods. Calgary columnists gave Nenshi the stink eye when he broke with tradition and endorsed all the incumbent councillors, without distinction, in the election—even the ones identified as anti-Nenshi good guys by the developer cabal.

The feeling seemed to be that it was a stunt designed to prop up Nenshi’s beleaguered friends on council. But what was stopping him from just doing that explicitly and letting the developer-certified councillors take their chances? Far be it from us to accuse a politician of telling the simple truth, but Occam’s razor suggests Nenshi may actually appreciate some give-and-take in the makeup of his council.

“I think I’m unusual in that when I bang the gavel to start a meeting, I actually have no idea what’s going to happen,” he says. “Sure, by noon most days I regret that the council doesn’t just do what I told them to. Our meetings go on forever because people are actually listening to one another and changing their opinions. It’s a bunch of good-natured people arriving at a decision, and as mayor I go before the cameras and defend that decision even if I didn’t agree with it.” Among his staff, Nenshi jokes, the firm rule is that the mayor is always right; but that rule is law only as far as the door of his office. Beyond that threshold, he’s just another Calgarian. COLBY COSH

03: Jerry Dias

|

As the president of Unifor, the mega-union created this year by the merger of the Canadian Auto Workers and the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers, Dias is expected to halt, or even reverse, the decline in Big Labour’s clout. He’s promised to organize workers not usually brought under the umbrella of industrial unions. For now, he leads an impressive 300,000-plus membership across two dozen economic sectors, mainly in manufacturing, communications and transportation. A native of Burlington, Ont., Dias follows in the footsteps of his father, a union local leader at de Havilland, now owned by Bombardier. The junior Dias’s first job was delivering parts around that plant. He soon became a shop steward. His ascent to the top of the union hierarchy is now complete. The question is: What will Dias do with a position that is, arguably, unprecedented in Canadian union history? JG

As the president of Unifor, the mega-union created this year by the merger of the Canadian Auto Workers and the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers, Dias is expected to halt, or even reverse, the decline in Big Labour’s clout. He’s promised to organize workers not usually brought under the umbrella of industrial unions. For now, he leads an impressive 300,000-plus membership across two dozen economic sectors, mainly in manufacturing, communications and transportation. A native of Burlington, Ont., Dias follows in the footsteps of his father, a union local leader at de Havilland, now owned by Bombardier. The junior Dias’s first job was delivering parts around that plant. He soon became a shop steward. His ascent to the top of the union hierarchy is now complete. The question is: What will Dias do with a position that is, arguably, unprecedented in Canadian union history? JG

04: Mark Wiseman

|

As president and CEO of the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, Wiseman presides over a $183-billion portfolio that amounts to the national nest egg: 18 million Canadians need him not to screw up. That doesn’t mean his investment decisions are always dull. He’s cut a deal, for example, with Formula One racing. And he fought Barrick Gold over what he saw as an excessive signing bonus for a corporate executive. At just 43, Wiseman stands to be a major figure in Canadian business for decades to come. JG

As president and CEO of the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, Wiseman presides over a $183-billion portfolio that amounts to the national nest egg: 18 million Canadians need him not to screw up. That doesn’t mean his investment decisions are always dull. He’s cut a deal, for example, with Formula One racing. And he fought Barrick Gold over what he saw as an excessive signing bonus for a corporate executive. At just 43, Wiseman stands to be a major figure in Canadian business for decades to come. JG

05: France Charbonneau

|

For several days this past spring, Frank Zampino was the picture of sour-faced indignation. An accountant by trade and elbows-first politician by instinct, Zampino spent 22 years in Montreal politics, including seven as president of the city’s executive committee. Since retiring in 2008, Zampino has been charged with fraud, conspiracy and breach of trust for an alleged lowball sale of city land to a favoured contractor.

This wasn’t the source of Zampino’s ire. Rather, it was being compelled to answer questions as a witness of Quebec’s commission into the province’s construction industry, chaired by Superior Court Judge France Charbonneau. Faced with damning evidence from his City of Montreal agenda, which listed meetings with allegedly mobbed up construction magnates, Zampino questioned the authenticity of the documents.

France Charbonneau clicked on her microphone angrily. “Are you suggesting the documents were falsified?”

Zampino, flustered, said something about the entries “not reflecting reality.”

“Oh really?” Charbonneau said, chuckling. When Zampino blubbered something else, she cut him off. “I’m going to assure you right now, Mr. Zampino, there was no falsification or crookedness on the part of the commission,” she said, clicking off her microphone with a stab of her finger.

For a raft of Quebec politicians, fundraisers, bureaucrats, construction company owners, union leaders, alleged mobsters and the occasional lawyer, an indignant Charbonneau has become a familiar, frightful sight. Officially known as the“commission of inquiry into the granting and management of public contracts in the construction industry,” the Charbonneau commission—and, especially, Charbonneau herself—has come to represent Quebec’s collective disgust with corrupt elements within it.

Having a judge—a woman, no less—dress down the alleged pillars of Quebec’s corruption-laden status quo on live TV has had a cathartic effect, and enthralled much of Quebec’s male commentariat. “She is a sphinx who devours the victims in front of her,” communications specialist Bernard Motulski said in a radio interview in June.

In short, Charbonneau has immense power, through both the wide mandate of the commission and her crusader status. On leave from the Superior Court, Charbonneau has all the legal powers of her former day job, including the right to compel testimony from uncooperative types like Zampino. At the same time, though, some wonder whether Charbonneau’s attack on Quebec’s government and construction industry has convicted individuals before their day in court—that her pursuit of justice is fuelled in part by a desire to satisfy the public’s lust for blood. “She convicts people with her eyebrows,” says one political organizer.

To be sure, the commission was formed in the crucible of widespread public outrage at the then-governing Liberals. For years, allegations surrounding the party’s fundraising apparatus, and its ties to construction and engineering firms, trickled out. Premier Jean Charest rebuffed calls for an inquiry into the construction industry, claiming it would imperil police investigations. For the opposition and a large swath of the public, it was proof the Liberals had something to hide.

Bowing to pressure, Charest called an inquiry in October 2011, naming Charbonneau as its head at the suggestion of Superior Court Chief Justice François Rolland. Originally Charest didn’t plan to give her the power to subpoena witnesses, but after two weeks of criticism he relented.

These powers put Charbonneau, a crown lawyer for 25 years before becoming a judge in 2004, in her element. She filled the commission with like-minded prosecutors and began pursuing the biggest players in the industry, and the bureaucrats and politicians who allegedly worked with them. “What became clear was her experience and understanding of how organized crime establishes itself and spreads,” says a former Charest adviser. “Because there were so many police investigations, we needed someone who wouldn’t infringe on the work of police.”

Charbonneau certainly had a keen understanding of how law enforcement worked. As a prosecutor she’d overseen 80 trials, including some of Quebec’s most high-profile cases. She successfully prosecuted Patrick Moïse for the 1989 murder of a gay CEGEP student, one of Canada’s first documented cases of sexuality-based hate crimes. She was also prosecutor in the murder trial of Robert Leblanc, accused of killing 22-year-old Chantal Brochu in 1992. Charbonneau knew Leblanc was guilty—he’d admitted as much to a judge in pretrial testimony—yet had to convince an unknowing jury of his guilt. It worked: Leblanc remains in jail.

Charbonneau’s reputation as a steely prosecutor was cemented with her conviction of Maurice “Mom” Boucher, one of Quebec’s most notorious criminals. Boucher, a leader of Quebec’s “Nomad” chapter of the Hells Angels biker gang, was arrested on charges stemming from the murder of two prison guards in 1997. Charbonneau, who wasn’t the lead prosecutor in the case, could only watch as a smirking Boucher was found not guilty the following year. Charbonneau pushed for and secured an appeal on the condition she be the lead prosecutor. It was a difficult case, and not only because she was the subject of death threats. Boucher wasn’t at the scene of the crime, but had ordered underlings to do the deed. Charbonneau argued Boucher demanded absolute loyalty from his charges—including Stéphane Gagné, a Hells Angels hanger-on turned police informant who testified he received orders from Boucher to kill the guards.

Her gambit worked: Boucher looked stunned as he was found guilty in May 2002. “People can have confidence in their justice system,” Charbonneau told reporters.

She won that case in part by attacking the credibility of Boucher’s lawyer, Jacques Larochelle—a man filled with “scorn, disgust and condescension,” Charbonneau told the jury. She also admonished presiding judge Pierre Béliveau for chuckling during arguments, insinuating he favoured the defence.

Shades of prosecutor-era Charbonneau are on offer in her current role. “Are you an imbecile and incompetent?” she asked witness Robert Marcil last February, after the former public works director uttered his umpteenth “I can’t remember.” She reminded reluctant witness Nicolo Milioto he didn’t “get to determine the pertinence of the questions” when the construction executive balked at commenting on his ties to the Rizzuto crime family. As with Zampino, her admonishments were delivered with sang-froid—and, yes, often with an incredulous arched eyebrow.

It has led some in the legal community to wonder whether Charbonneau and the commission lawyers are playing for the camera. “This kind of thing would not be allowed in a courtroom,” says one lawyer representing a commission witness. The lawyer related how two investigators showed up at the client’s law offices. “One, trying to encourage the client to testify before the commission, said, ‘Your client has every interest in testifying before the television.’ I asked him if he meant commission, which was, of course, what he had intended to say. It was hard to know if it was a slip of the tongue, or if, for him, the words had become interchangeable.”

The commission’s roughly 20 inspectors make pains to verify and cross-check witnesses. But mistakes have slipped through. Martin Dumont, an organizer with former Montreal mayor Gérald Tremblay’s Union Montréal, testified about a secretary having to count $850,000 in cash donations to the party—a story he later admitted was false. Dumont also testified he was in a room when a union representative made reference to Tremblay while discussing the party’s “unofficial” donor lists. Though Dumont maintained the story was true, he only remembered Tremblay’s presence after meeting with commission investigators. Tremblay denied the allegations; nevertheless, he resigned within days.? By and large Montrealers didn’t spare a thought for their long-suffering mayor. Mostly they were just happy to see him go, and gave the credit to Charbonneau herself. “Charbonneau benefits from the cynicism people have toward the political and business class,” says Pierre Tremblay, a professor of political science at Université de Québec à Montreal. “She has incredible powers as well as a very favourable climate in which to use them.”

Charbonneau is expected to table her report in early 2015. For good or ill, it’s perhaps her most powerful achievement: from mobsters to politicians, she has just about everybody worried. MARTIN PATRIQUIN

06: Ray Novak

|

When Nigel Wright revealed his role in the repayment of Mike Duffy’s expenses—a scheme the Prime Minister recently described as a deception—Stephen Harper turned to the one person he should be able to trust: the aide who has been by his side for a dozen years, the one who, famously, lived in the loft above the garage at Stornoway when Harper was leader of the opposition. Once Harper’s executive assistant, Novak had risen to the position of principal secretary and carried a reputation as a discreet and loyal operator who could get things done. Other than Laureen, nobody knows the Prime Minister better than the loyalist who’s now his chief of staff. AARON WHERRY

When Nigel Wright revealed his role in the repayment of Mike Duffy’s expenses—a scheme the Prime Minister recently described as a deception—Stephen Harper turned to the one person he should be able to trust: the aide who has been by his side for a dozen years, the one who, famously, lived in the loft above the garage at Stornoway when Harper was leader of the opposition. Once Harper’s executive assistant, Novak had risen to the position of principal secretary and carried a reputation as a discreet and loyal operator who could get things done. Other than Laureen, nobody knows the Prime Minister better than the loyalist who’s now his chief of staff. AARON WHERRY

07: Galen Weston Jr.

|

With his $12.4-billion bid for Shoppers Drug Mart Corp., the boss of Loblaw Companies Ltd. and scion of one of Canada’s biggest family fortunes served notice he wouldn’t be a stand-pat heir and President’s Choice TV shill. The deal, if it goes through, gives Canada a homegrown, credibly scaled rival to the likes of Target Corp., which plans to open 124 stores in Canada this year, and Wal-Mart, which continues to rapidly expand its Canadian operation, not to mention the next wave of entrants, such as Nordstrom, the American department store that’s coming soon. Weston has his work cut out for him, but his audacious deal with the country’s largest drug retailer, plus the success of his Joe Fresh clothing line and the lasting appeal of PC products, gives the bespectacled billionaire a fighting chance. JG

With his $12.4-billion bid for Shoppers Drug Mart Corp., the boss of Loblaw Companies Ltd. and scion of one of Canada’s biggest family fortunes served notice he wouldn’t be a stand-pat heir and President’s Choice TV shill. The deal, if it goes through, gives Canada a homegrown, credibly scaled rival to the likes of Target Corp., which plans to open 124 stores in Canada this year, and Wal-Mart, which continues to rapidly expand its Canadian operation, not to mention the next wave of entrants, such as Nordstrom, the American department store that’s coming soon. Weston has his work cut out for him, but his audacious deal with the country’s largest drug retailer, plus the success of his Joe Fresh clothing line and the lasting appeal of PC products, gives the bespectacled billionaire a fighting chance. JG

08: Justin Trudeau

|

Last time, we put Trudeau on the list primarily on the strength of his social media presence, especially his Twitter following. Now, as Liberal leader, he’s keeping his party near the top of opinion polls. His ability to dictate the public debate—as he did over the summer by talking about marijuana, both having smoked it and wanting to legalize it—is currently unrivalled. But as his showing during the Senate scandal demonstrates, he faces a steep learning curve on the floor of the Commons. JG

Last time, we put Trudeau on the list primarily on the strength of his social media presence, especially his Twitter following. Now, as Liberal leader, he’s keeping his party near the top of opinion polls. His ability to dictate the public debate—as he did over the summer by talking about marijuana, both having smoked it and wanting to legalize it—is currently unrivalled. But as his showing during the Senate scandal demonstrates, he faces a steep learning curve on the floor of the Commons. JG

09: Julie Dickson

|

While heading the federal Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions, Dickson has emerged as a star among international advocates of tougher banking regulation in the wake of the 2008 global credit meltdown. She’s due to end her seven-year term at OSFI next year, but that leaves plenty of time for Dickson to stare down financial-institution bosses who’d like to be a bit more freewheeling. She wields power over Canadian mortgage markets and bank capital requirements, and her voice is heard far beyond Canada’s borders—wherever debate rages about how to prevent another global banking crisis. JG

While heading the federal Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions, Dickson has emerged as a star among international advocates of tougher banking regulation in the wake of the 2008 global credit meltdown. She’s due to end her seven-year term at OSFI next year, but that leaves plenty of time for Dickson to stare down financial-institution bosses who’d like to be a bit more freewheeling. She wields power over Canadian mortgage markets and bank capital requirements, and her voice is heard far beyond Canada’s borders—wherever debate rages about how to prevent another global banking crisis. JG

10: Mike Lazaridis

|

|

These days Mike Lazaridis keeps an office in a three-storey building in the University of Waterloo’s sprawling and non-descript industrial research park. The deposed BlackBerry founder’s business card carries the name of his holding company: “Infinite Potential Group.” The name sounds designed to be meaningless until you realize Lazaridis means it at face value. The group he is assembling really does have infinite potential.

To get an interview with Lazaridis I pestered him for three months through intermediaries who made me promise I would ask no question about BlackBerry, the company he co-founded, lost and is, reportedly, trying to buy back. I didn’t mind. BlackBerry is hardly the only thing on his plate now. Lazaridis is on the hunt for vastly bigger game than smartphones.

“What a few of us are saying is, there’s a potential here for a new paradigm, the next quantum revolution,” Lazaridis said.

Around Waterloo, Ont., Lazaridis and a few associates have started calling the region west of Toronto the “Quantum Valley,” a conscious echo of Silicon Valley in northern California. There, beginning in 1957, a few refugees from Bell Labs launched the global semiconductor industry, whose total value half a century later is measured in trillions of dollars. Lazaridis has been moving aggressively to launch and lead a comparable revolution: the era of quantum technology.

In March, with BlackBerry co-founder Doug Fregin, Lazaridis announced the creation of Quantum Valley Investments (QVI), a $100-million venture capital firm that will invest only in businesses that want to exploit quantum technology. There is only one other like it in the world, Quantum Wave, launched last year in Atlanta with Russian money. But QVI builds on more than a decade of expertise Lazaridis has been gathering in Waterloo.

His first move was the creation of the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in 1999 to explore fundamental questions in physics, such as the nature of space and gravity, the composition of the atom, and so forth. Perimeter makes nothing but theories. Its standard work tool is chalk on chalkboards. In 2002, Lazaridis launched his project’s experimental phase, the Institute for Quantum Computing (IQC). Spilling across three buildings including the year-old, state-of-the-art 280,000-sq.-foot Quantum Nano Centre, IQC is home to 200 scientists trying to turn theory into working prototypes for a new technology.

And that’s where Lazaridis originally planned to leave things, because he didn’t think there would be workable quantum technology in his lifetime. “I was going to leave it to other people to do.”

Quantum technology depends on the peculiar properties of matter at the smallest scale, the scale of atoms. Classical information technology, the stuff we use every day, is built from tiny switches, or “bits,” that can either be on or off. But at the atomic scale, things get so weird it is a challenge even to describe them. An individual atom in its new role as a quantum bit can be on, off—or both at the same time. Quantum particles can become “entangled” so that a change in one particle is reflected by an identical change in the other—instantly, across any distance. These properties are so close to magic that it’s perhaps appropriate that they only happen out of sight: as soon as humans attempt to measure what’s going on in a quantum system, it loses its “quantum-ness.”

But the potential payoff from this strangeness is vast. The “superposition” of quantum bits—their ability to be on, off and both at the same time—means that quantum computing power increases geometrically. Two quantum bits, or “qubits,” can hold as much information as four classical bits, three as much as eight—and 500 could hold and process far more information than the largest computer yet built.

The trick is to make them. The state of the art is rudimentary. When Lazaridis hired a soft-spoken, Quebec-born student of Stephen Hawking’s named Raymond Laflamme to be the director of the Institute for Quantum Computing in 2002, Laflamme had built a five-qubit “computer,” an incredibly finicky tinker toy. Laflamme is up to a dozen qubits now; he hopes to have machines with 50 to 100 qubits in the next five years. To get this far, Lazaridis has paid $200 million of his own money, an amount roughly matched by a series of investments over 13 years by the Ontario and federal governments.

But four or five years ago, Laflamme started to report to Lazaridis that progress toward quantum computers is faster than expected, and the road is not empty of landmarks. It will take an unimaginable string of breakthroughs to get to workable quantum computers—but because the field is so new, every single breakthrough along the way has an immediate practical application. Each discovery Laflamme and his colleagues makes has provided something that could go on the market for profit.

Laflamme showed me sheets of factory-made diamond with precisely inserted impurities, individual atoms poked into the carbon lattice with microscopic accuracy. The resulting material has quantum properties. He showed me a sensor made of silicon and etched aluminum. An IQC researcher, Adrian Lupascu, had an insight: If quantum states are incredibly delicate and prone to break down, their very fragility can make them useful for sensors. “These are the best magnetometers there are, the size of microns . . . an order of magnitude more sensitive than anything else.” They’ll have applications in medical imaging, manufacturing and microscopy.

Laflamme has been recruiting world-class scientists at an accelerating pace: materials scientists, engineers, theorists. His biggest catch by far is David Cory, a nuclear engineer the University of Waterloo poached from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2010 with a $10-million federal grant. Nobody in the world is better at understanding the odd language of quantum particles or in spotting their real-world applications. He came to Canada with three 18-wheelers full of lab equipment. That posed the sort of challenge Lazaridis likes to solve.

When the federal grant competition was announced, Laflamme said, “David was obviously a target. This building was not ready. The question was, how do you bring him here, but leave him with no room for a year or two?”

Lazaridis was at the table when Laflamme explained his dilemma: For the next two years he would have only temporary digs, and he needed Cory right now. “So Mike looked up and said, ‘Would another building like this work?’ I said yeah. He said, ‘I’ll get back to you.’ That was around 10 a.m. At around noon he said, ‘We have a deal. I talked to the president of the university, I have a partner.’ ” The IQC expanded to fill the building next door, and when the new building opened in 2012, the two other buildings stayed in service.

Cory, wild-haired and bearded like an aging California surfer, showed me room after room of laboratories, moving at a speed just short of a run. “Here we have NMR systems, so they’re big superconducting magnets,” he said at one point. “A 10 millikelvin vacuum can,” able to produce temperatures a fraction of a degree above absolute zero. “X-ray diffraction.”

Pieces of equipment the size of household refrigerators were connected in long chains, in a hodgepodge as cheerfully improvised as a high-school chemistry lab but with equipment thousands of times more delicate and powerful. “Every room should be a lab, in my view,” Cory said, peering into a cubicle the size of a graduate student’s office. “Here we grow diamonds,” he said in another room across the hall. “We can grow about a micron of diamond an hour.”

Cory has an unusually large team of graduate students and post-doctoral assistants from a wide variety of disciplines. The entire team meets every morning. Nobody is allowed to work on individual projects. They have found applications for their work in medical imaging and in deep-sea oil exploration. “We’ve started exploring with the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre” in Toronto, Cory said. “Just an open-ended discussion. How can quantum sensors make a difference? And there’ll be many ways. It’ll build on old work we did at the Dana-Farber cancer centre in Boston, using quantum sensors to set the edges of soft-tissue sarcomas.”

In September, IQC named its two latest recruits. Amir Yacoby comes from Harvard University and is a world leader in developing these exotic materials that can hang onto quantum characteristics. Steve MacLean is an astronaut: he served on the International Space Station in 2006 and was the president of the Canadian Space Agency from 2008-13. But MacLean is also a physicist who was setting up an elaborate experiment in his garage—he won’t discuss details—when he bumped into Lazaridis a few years ago at Cape Canaveral before a space shuttle launch. “We ended up talking for two hours about everything and nothing.” Soon MacLean had offices at Perimeter and at IQC. He also serves on the advisory board of the new venture-capital firm.

What are they doing? MacLean won’t say. “Um. I mean, I know the answer to that,” he said, when I asked him how many business plans QVI is adjudicating. “There are many non-disclosure agreements.”

All the research at Perimeter and IQC is public, as at any university. Just about everything to do with QVI is private. This is what happens when science moves into the fiercely competitive world of business.

“You know what I’m doing by doing that?” MacLean said in an attempt to explain his silence. “I’m protecting Canada in a way. I mean, this is a community effort that we’re doing here and we have certain leads in certain areas and I just would like you to focus on the fact that it’s unique.”

Only Lazaridis can talk about what goes on at QVI. He doesn’t say much either. But he reveals that the fund has made its first investment. “Actually, we only went public after we did our first investment.”

What’s the investment?

“I can’t tell you that.”

What’s the scale of the investment?

“It’s big.”

What field is it in? Is it in sensors? Cryptography?

“Those were already announced before we made our investment. Our investment is different.”

Will it lead to products on the market? Yes, Lazaridis said, perhaps in two or three years. Products for consumers? “I can’t really tell you.”

He finally said that the entrepreneur QVI just funded is “a guy from around here” and that when he wrote an equation on a blackboard, “I said, ‘We have to invest in this.’ This is not just an improvement, this is not just a new way of doing a classical thing that we’re all used to. This is something new.”

He is being coy. But he is not just being coy. Quantum technology is not just a new method of making computers, it is a vast new field of technologies that have never existed before. If Quantum Valley is the new Silicon Valley, this year may be the equivalent of 1957, and decades more work may lie ahead. When the founders of Fairchild Semiconductor were asked back then to explain what a transistor is for, one of them said it might make a better hearing aid. There was no way to imagine iPhones and GPS navigation and the trillion-dollar economy that followed.

A half-dozen countries are financing major quantum technology efforts, including China, the U.S. and the United Kingdom. It is easy for venture-capital firms to bet big on companies that flop. QVI may be just the latest in Mike Lazaridis’s 14-year-old, very expensive fascination with weird science. Or it may launch a new century of innovation. Of all the people in this Power List, Lazaridis’s potential clout will be felt, if at all, over the longest time span, with the highest risk of failure. But if it pans out, he and his associates will change the world.

“This is a new technology. How do you predict where you’re going to wind up? There is no classical counterpart. You can’t just go back and say, ‘This is a better version of that.’ And that’s the part that gets me excited.” PW

11: Gerald Butts

|

Trudeau’s top adviser is as close as can be imagined to the potential next prime minister. He has guided every step of the Liberal leader’s rise so far, and is positioned to remain, to borrow an old phrase, close to the charisma for years to come. They have been close since meeting as McGill University students. Butts went on to be principal secretary to then-Ontario premier Dalton McGuinty before becoming president and CEO of World Wildlife Canada. From his Ontario government years, Butts brings front-line, hard-earned political experience that Trudeau lacks. As well, Butts is the son of a Cape Breton coal miner, possibly a useful corrective to the experience and instincts of the son of an iconic Liberal prime minister. JG

12: Beverley McLachlin

|

At 70, she’s already the longest-serving chief justice of the Supreme Court of Canada (having passed the previous record-holder, Sir William Ritchie—1879 to 1892). Handling the Senate reference this fall will remind us that McLachlan is a central figure, as she has been since taking over the helm of the top court in 2000. And there will be many more big decisions to come from the McLachlin Court if she makes good on her recent comments about her intention to remain the country’s top judge until her mandatory retirement at 75. JG

13: Thomas Mulcair

|

Mulcair’s power is undeniably diminished by Trudeau’s ascent. Before Trudeau, Mulcair was the guy on the Opposition benches everybody was watching. Now, he has to compete with Trudeau for attention—and more often than not, so far, has come up short. However, Mulcair still heads the official Opposition,which means he gets to lead question period anyway. That matters. Mulcair proved it last spring with a prosecutorial assault on Harper over the Senate, and showed the same tough form often this fall. He might not have Trudeau’s celebrity, but political opportunism allows him to score when the news of the day calls for his particular combative skill set. JG

14: James Moore

|

|

In the late summer of 2000, a recent political science graduate at the University of Northern British Columbia sat on the floor of his basement apartment in Prince George, B.C. A fall federal election was in the wind, and he used a Sharpie to draw the outlines of his home riding, a suburban Vancouver constituency held by a Liberal MP, on a Frommer’s map. Also arrayed around him were his old high school and junior high yearbooks. If he could identify just 250 friends and acquaintances back home who would support him, he figured that might be enough to get himself nominated as the Canadian Alliance candidate, and then try to capture the seat.

Unlike many dream-job schemes, it worked. At just 24, James Moore won Port Moody-Coquitlam-Port Coquitlam under Stockwell Day’s Alliance leadership, making him B.C.’s youngest MP ever. He has held the riding easily through four elections since then. During that stretch, he saw Day falter and fade, and the Alliance merge with the old Tories to form a new Conservative party under Stephen Harper. Along the way, Moore evolved from an unusually young and vocal opposition backbencher, to one of Harper’s designated question period scrappers, to one of his most prominent cabinet ministers and regional chieftains. He’s still only 37. Promoted to the Industry Canada portfolio in last summer’s cabinet shuffle, after a fairly high-profile stint as heritage minister, Moore’s rise from student striver to key economic minister happened fast.

Yet he is not entirely content. He worries that the public sees politicians only when they’re behaving badly, especially in question period—and even then some of the worst stuff isn’t captured on camera. And he doesn’t exclude himself from criticism. “Look, I’ve had my moments that I’m not proud of,” he says of the 45 minutes of daily sparring in the House. “The public sees people losing their cool on camera. What they don’t hear are some of the pretty boorish, aggressive and personal heckles, and people being teased for their weight”—he’s a big man—“their hair, their gender, their tie. It can be really awful at times.”

Moore adds that he’s frustrated to turn on the TV news at the end of day when he might have attended two cabinet committees, met with a top CEO, and grappled with a departmental policy file—only to hear that the Senate controversy alone rates a story. Still, he didn’t arrive exactly unprepared for the bruising side of politics. In fact, Moore’s apprenticeship was in perhaps the only forum less decorous than QP—talk radio. As well, he’s conscious of how politics in his home province, more than most places, traditionally lines up along bitter, ideological divides.

He grew up in Coquitlam, just outside Vancouver, son of a dentist father and a teacher-turned-homemaker mother. A serene suburban upbringing was broken by his mother’s sudden death from cancer in 1993, when he was 17. It changed his priorities. “After my mom died,” he says, “I decided to do more than save money for a Jeep.” Politics seemed a way to make life matter. He volunteered for Preston Manning’s Reform insurgency in that year’s federal election. Tilting right wasn’t an act of rebellion; his dad had raised money and put up signs for B.C.’s Social Credit party. But Moore also says Let the Trumpet Sound, Stephen B. Oates’s then newly published biography of Martin Luther King, Jr., had impressed him deeply, and he drew a line from civil rights idealism to Manning’s arguments for individual and provincial equality before the law.

The 1993 election was a watershed. Jean Chrétien’s Liberals won, but Manning’s Reformers and Lucien Bouchard’s separatist Bloc Québécois burst into prominence as the Tories were nearly wiped out. Working on the campaign, Moore met a right-wing Vancouver talk radio host, and ended up guesting on her show. Soon he was a fixture on the city’s airwaves. After the 1997 election, he moved to Ottawa to work briefly as a communications assistant to Manning, whose influence remains powerful. Moore describes Manning as providing, even now, a rare “generational perspective” on policy and politics, and he contrasts the elder statesman’s long view with the reality of governing, where “everything is a three-year cycle, a two-year pilot project, a five-year economic plan.”

Getting a taste of Ottawa with Manning, Moore realized his lack of higher education mattered. He went home to enrol in the University of Northern B.C. One of his professors, John Young, remembers his new student coming up after his first American politics class to mention that he was running his own website on B.C. politics. “I checked out the website and thought, ‘Okay, this young man is already a good notch above many,’ ” Young recalls. Moore not only dominated in-class debates (“Other students were a bit reluctant to go up against him,” Young says), he also hosted a show on a Prince George radio station.

In 2000, Moore vaulted pretty much from a seat in a classroom to one in the House of Commons, and yet says a long career in federal politics didn’t seem likely to him then. Day had fared well in B.C., but his failure to break through in Ontario, where Chrétien’s Liberals continued their dominance, left him vulnerable. Revolt broke out in the Alliance caucus. As well, Chrétien was likely to be succeeded by Paul Martin, whose “Blue Liberal” credentials, Moore says, were expected to play well in the West. So the B.C. rookie saw himself as a likely “one-term wonder.”

He says two unrelated developments changed that. The first was the terrorist attack on New York and Washington on Sept. 11, 2001. The Alliance’s internal squabbling faded quickly to irrelevance that day. Moore and other opposition MPs threw themselves into parliamentary work, as the Liberals forged new security and anti-terrorism policies. “We said, whether our political party will survive, all that is secondary,” Moore says. The following year, Day called a leadership race in a bid to solidify his hold on the Alliance, but was instead beaten by Harper, who came back to politics after a hiatus as head of the National Citizens Coalition. His return, and his success in reuniting the Canadian right, is the second factor that Moore credits with prolonging his federal political life.

When Harper won the 2006 election, he didn’t elevate Moore to cabinet right away. But as a parliamentary secretary, Moore was handed plum responsibilities for the upcoming Vancouver 2010 Olympics. In the 2008 campaign, Harper’s remark that cutting arts funding “isn’t something that resonates with ordinary people” hurt him. In Quebec, those cuts were an unexpectedly big issue. After the election, Moore was named heritage minister and assigned to repair the damage. A product of immersion education through elementary and high school, he speaks French well. Money also talks, though, and he points to Canada Council funding increases and the creation of the Canada Media Fund, which supports production of TV and digital programs, as having helped the Tories with the skeptical arts and entertainment sectors.

Perhaps his most delicate Heritage file was the CBC. In last year’s federal budget, the Harper government cut the public broadcaster’s funding 10 per cent, from $1.1 billion, over three years. Moore suggests the CBC must now secure its own future. “It’s for them to find their relevance, present it to Canadians, and if Canadians support it, they’ll continue funding it. If not, it will disappear,” he says, Moore also left his mark on national identity issues, pushing history projects like the 200th anniversary of the War of 1812 and launching plans for Canada’s 150th birthday in 2017.

Moving to Industry last summer gave him a chance to prove himself in an economic post. Jason Kenney made a similar transition, to Employment from Citizenship and Immigration. Tory insiders see both as likely future leadership aspirants. Moore is striking a pro-consumer stance, talking about how cable companies should give viewers better options to “pick and pay” for only the channels they want and promoting more competition among cellphone companies. Still, exactly how he hopes to accomplish either goal remains largely a mystery. On more cell choice, Verizon’s decision not to enter the Canadian market was a serious setback. Opposition MPs see Moore creating high expectations without obvious policy solutions in hand. “He’s one of the better ministers,” says NDP consumer protection critic Glenn Thibeault. “However, he’s got no plan in place.”

Perhaps even more than his demanding policy file, though, Moore is identified with his province. He says B.C. has only lately moved from its traditional position on the periphery of national affairs to the centre. Fierce debate about pipelines to the Pacific has made talk of B.C.’s proximity to Asian markets feel far more important. Environmental issues carry huge national consequences. Aboriginal policy is being cast in a new light by developments like B.C.’s Nisga’a Nation’s moving recently to let its members privately own tribal land, a first for a Canadian Native community. With all this in play, the old B.C. politics of polarized, left-right extremes feels to Moore outmoded. “There’s a maturation because now we matter,” he says. “It’s time for B.C. to step up and step forward.” And an auspicious moment to emerge as province’s leading figure on the federal stage. JG

15: Christy Clark

|

Her astounding comeback in the last British Columbia provincial election left professional pollsters sheepish and the B.C. premier in a position of power. But energy development as a path to economic successes poses big challenges. Clark is banking on up to 10 liquefied natural gas projects to create thousands of jobs. This month she secured a framework agreement with Alberta that would provide unspecified economic benefits to B.C. if a proposed pipeline to bring Alberta oil-sands crude to a Pacific port ultimately goes ahead. JG

Her astounding comeback in the last British Columbia provincial election left professional pollsters sheepish and the B.C. premier in a position of power. But energy development as a path to economic successes poses big challenges. Clark is banking on up to 10 liquefied natural gas projects to create thousands of jobs. This month she secured a framework agreement with Alberta that would provide unspecified economic benefits to B.C. if a proposed pipeline to bring Alberta oil-sands crude to a Pacific port ultimately goes ahead. JG

16: Pierre Karl Peladeau

|

Even though he stepped down as CEO of Quebecor in May, Peladeau is still its largest shareholder and chairman of its media and television branches. PKP, as he’s known, controls everything from TV news and talent shows, to Montreal’s leading tabloid newspaper and supermarket checkout-line magazines, to the Canada-wide Sun News TV and print brand. Last April, Quebec Premier Pauline Marois made him chairman of Hydro-Québec, the province’s electricity transmitter. He’s after an NHL franchise for Quebec City. And he’s a tireless promoter of entrepreneurship in Quebec. JG

Even though he stepped down as CEO of Quebecor in May, Peladeau is still its largest shareholder and chairman of its media and television branches. PKP, as he’s known, controls everything from TV news and talent shows, to Montreal’s leading tabloid newspaper and supermarket checkout-line magazines, to the Canada-wide Sun News TV and print brand. Last April, Quebec Premier Pauline Marois made him chairman of Hydro-Québec, the province’s electricity transmitter. He’s after an NHL franchise for Quebec City. And he’s a tireless promoter of entrepreneurship in Quebec. JG

17: Laureen Harper

|

|

Stephen Harper’s parents put him in the Royal Conservatory of Music program and, growing up, he regularly played classical pieces. After he married and moved in with Laureen Harper, the piano followed them from house to house. Laureen knew he was a big Beatles fan, so she started to leave the band’s sheet music on the piano. It was her subtle way of nudging him to bring out another side of his personality.

So it’s not surprising she was behind Harper’s performance at the Conservative convention in Calgary last month when he took the stage at Cowboys Dance Hall to play with the Ottawa band Herringbone, belting out Stompin’ Tom Connors’s The Hockey Song, followed by some Johnny Cash and BTO. “She would have orchestrated something like that,” says Laura Peck, vice-president of McLoughlin Media and a friend to Laureen. The performance, coming amid a convention dominated by the Senate scandal, made all of the major news networks and national and local papers, despite being a delegates-only event. For good measure she tweeted the video link to her 6,000 followers.

It was signature Laureen Harper, employing a tried-and-true tactic to soften her husband’s image. In 2009 she was the architect behind the Prime Minister’s surprise appearance at the National Arts Centre where he got on stage with Yo-Yo Ma and sang the Beatles’ With a Little Help from My Friends. Harper got a standing ovation, and the event drew national coverage for the NAC event, of which Laureen was the honorary gala chair. Even the Toronto Star ran the headline, “Stephen Harper rocks out.”

She does these things because they are fun but, at the same time, she is not oblivious to the benefits. Laureen Harper’s brand of power, while highly effective, is not always obvious. It comes in part from who she is—personable and passionate, skilled in subtle, quiet persuasion. She is able to draw people to step out of their comfort zone, and not just her husband.

These abilities dovetail with her charity work. She fosters cats for the Humane Society and has placed many felines in the homes of senior politicians, lobbyists, journalists and friends. She attracts large donations to her favourite charities and is sought after by organizations to help raise their fundraising profiles. Over time Laureen has expanded beyond her earliest cause, animals, to helping a long list of other groups, including the anti-bullying movement and several arts organizations. “She takes on things she can be most effective at and runs the distance,” says Peck.

When the Harpers first arrived in the nation’s capital from Calgary, they did not fit into the Ottawa crowd. “They didn’t care because they just wanted to be themselves,” says someone who has spent time around the couple. Laureen helped them integrate.

Those who know her well say she should not be underestimated. She is strategic about politics too—she speaks off the record to certain Ottawa journalists, reads the media coverage closely and is social-media savvy. She does not speak publicly about policy but has very strong views. And while she looks after the philanthropic and entertainment side of life at 24 Sussex, hosting musicians like Jann Arden and Nickelback, she is also skilled at forming alliances, something her husband shies away from.

She has “great influence with and over different cabinet ministers,” says one source who is politically connected. Laureen is close to two cabinet ministers in particular—John Baird and Rona Ambrose—and they are genuine friends. But she also knows her strengths and her husband’s weaknesses, says the source. “She is more social than the Prime Minister and this helps strengthen the bonds and fidelity these ministers have with the PM. She is able to do some of the relationship nurturing that he is not known for. That is very valuable.”

It is why Conservatives call her Harper’s secret weapon. JULIE SMYTH

18: Jason Kenney

|

As Harper’s Citizenship and Immigration minister, he redefined citizenship in Conservative-friendly ways and sought new Conservative votes among immigrants. In the summer shuffle, Kenney became minister of employment and kept his responsibility for ethnic outreach. The new role gives him experience in an economic portfolio he may need if he ever runs to replace Harper as Conservative leader. And since his job has always been to advance Conservative electoral chances, there’s no reason to believe that’s changed with his new role. JG

As Harper’s Citizenship and Immigration minister, he redefined citizenship in Conservative-friendly ways and sought new Conservative votes among immigrants. In the summer shuffle, Kenney became minister of employment and kept his responsibility for ethnic outreach. The new role gives him experience in an economic portfolio he may need if he ever runs to replace Harper as Conservative leader. And since his job has always been to advance Conservative electoral chances, there’s no reason to believe that’s changed with his new role. JG

19: Alex Pourbaix

|

The protests and political turmoil that have delayed Washington’s approval of TransCanada Corp.’s proposed Keystone XL pipeline served as a tough lesson for the Calgary company’s president of energy and oil pipelines. And Keystone isn’t dead yet— President Barack Obama is now expected to make a decision by late winter or early spring. But TransCanada exec Pourbaix might have a better bet with his proposed $12-billion Energy East TransCanada pipeline, which Prime Minister Stephen Harper says he approves “in principle,” though the project must still get regulatory approval. If it does get the go-ahead, the new outlet for Alberta oil would see 3,000 km of existing natural gas pipeline converted to carry crude oil, as well as the construction of another 1,400 km of fresh pipe. The pipeline would terminate at a new marine terminal at Saint John, N.B. The project has its critics, but it will be a debate fought here in Canada. JG

20: Jenni Byrne

|

Shortly after Ray Novak took over as chief of staff, Jenni Byrne was tabbed as a deputy chief of staff—returning to the PMO from the Conservative party, where she was director of political operations. Byrne has a reputation as a tough partisan, but she also has history with the party (she joined the Reform party at 16) and a record of success (she directed the Conservative campaign in 2011). She might be the Prime Minister’s best political organizer, but she now has her work cut out for her. Byrne remains in her volunteer position as the Conservative party national campaign chair—a sign campaign preparations will be a priority for Harper. If the Tories are to revive themselves this year and be re-elected in 2015, she’ll have to succeed at both her PMO and party tasks. AW

21: Marc Caira

|

Taking over as Tim Hortons CEO this summer makes Caira not just a business figure but a cultural curator. The iconic purveyor of caffeine, sugar and carbs must fend off McDonald’s and Starbucks to maintain its Canadian market lead, while trying to boost its U.S. presence. Caira says he wants to bring speedier service and new food options—some of them healthier—while retaining that Tim’s Canadiana feel. JG

22: Steve Yzerman

|

The legendary former captain of the Detroit Red Wings was appointed as the executive director of the Canadian men’s Olympic hockey team in 2008. Two years later, the team won a hard-fought gold in Vancouver. Everybody likes to remember that one, and the 2002 gold in Salt Lake City. But the 2006 seventh place finish in Turin, Italy, and the 1998 fourth place in Nagano, Japan, were outright disasters for the team and national pride. More than anyone—other than, perhaps, team leader and NHL superstar Sidney Crosby—it is Yzerman who carries the burden of making sure the team succeeds in Sochi, Russia. JG

23: Heather Conway

|

Just chosen as the new executive vice-president of English-language services of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Conway will oversee a cultural empire—TV, radio and online services in the public broadcaster’s English services. Her path to the CBC’s most-watched job was unconventional; she was most recently chief business officer at the Art Gallery of Ontario, before that the head of Canadian operations for the international public relations firm Edelman’s. But she has broadcasting experience, from her six years as executive vice-president of marketing at Alliance Atlantis. Prior to that she was executive vice-president of corporate and public affairs for TD Bank Financial Group. All in, it’s a Toronto establishment resumé that marks her as a top executive, but still something of a wild card inside CBC’s often insular corporate culture. JG

24: Anne Merklinger

|

As head of Own the Podium, the former swimmer and curler is the executive responsible for making sure Canadians feel good about how athletes wearing the Maple Leaf perform at the world’s biggest sports showcases. Currently, Merklinger’s federal strategic fund is investing $33.8 million in summer Olympic sports for 2013-14 and $23.8 million for winter sports. At the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, Canada won 26 medals, including 14 golds, placing third overall in the medal count. That’s the target for the upcoming 2014 winter games in Sochi. Merklinger was among Canada’s best curlers in the ’90s. She went on to become a respected manager with national sports organizations like CanoeKayak Canada. Which is nice. But this is the Olympics. It’s the athletes we’ll be watching come February, but it’s Merklinger whose program will be put to the test. JG

As head of Own the Podium, the former swimmer and curler is the executive responsible for making sure Canadians feel good about how athletes wearing the Maple Leaf perform at the world’s biggest sports showcases. Currently, Merklinger’s federal strategic fund is investing $33.8 million in summer Olympic sports for 2013-14 and $23.8 million for winter sports. At the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, Canada won 26 medals, including 14 golds, placing third overall in the medal count. That’s the target for the upcoming 2014 winter games in Sochi. Merklinger was among Canada’s best curlers in the ’90s. She went on to become a respected manager with national sports organizations like CanoeKayak Canada. Which is nice. But this is the Olympics. It’s the athletes we’ll be watching come February, but it’s Merklinger whose program will be put to the test. JG

25: Andrew McCartney

|

As managing director at Tribal DDB Toronto, McCartney is one of the marketing minds behind the McDonald’s advertising campaign “Our Food. Your Questions.” The widely discussed campaign was built around a McDonald’s webpage where consumers ask thousands of questions on everything from whether the shakes are fake to how McNuggets are processed. McDonald’s answers. The digital campaign tried, and largely succeeded, to convey frank transparency through a production style far less glossy and jingly than a typical McDonald’s spot. Print and TV ads carried the same just-the-facts tone. Tribal won silver in the social media marketing category at prestigious Cannes Lions awards for advertising and related commercial promotions work. McCartney’s next moves are being closely watched. JG

26: Suzanne Fortier

|

The new president of McGill University comes to the prestigious post from a stint as head of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council. There, Fortier pushed the federal granting agency to focus on supporting research with direct commercial potential, and on using the federal fund to foster relationships between universities and companies. She’s been a vocal proponent of attracting women to science and engineering. Her return to McGill—she studied there after growing up in a village on the south shore of the St. Lawrence—comes at a tense time for higher education in Quebec. She’s expected to lead on many levels—campus, province and country. JG

The new president of McGill University comes to the prestigious post from a stint as head of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council. There, Fortier pushed the federal granting agency to focus on supporting research with direct commercial potential, and on using the federal fund to foster relationships between universities and companies. She’s been a vocal proponent of attracting women to science and engineering. Her return to McGill—she studied there after growing up in a village on the south shore of the St. Lawrence—comes at a tense time for higher education in Quebec. She’s expected to lead on many levels—campus, province and country. JG

27: Jim Flaherty

|

Having survived the Great Recession, the only finance minister Stephen Harper has ever had is also his cabinet’s most durable figure. Early this year he revealed that he’s battling a rare skin disease that has, at times, left him looking bloated and blotchy. Still he perseveres. His declared aim is to remain the government’s senior economic minister until the federal budget, which he plunged into deficit in 2009, is again balanced. He says red ink will dry up by 2015. That’s also, as it happens, the year of the next scheduled election. Will Flaherty run again? He’s been the MP for the Ontario riding of Whitby-Oshawa since 2006. He’s also the minister responsible for the Greater Toronto Area, which is shaping up as the key battleground for the next campaign. JG

Having survived the Great Recession, the only finance minister Stephen Harper has ever had is also his cabinet’s most durable figure. Early this year he revealed that he’s battling a rare skin disease that has, at times, left him looking bloated and blotchy. Still he perseveres. His declared aim is to remain the government’s senior economic minister until the federal budget, which he plunged into deficit in 2009, is again balanced. He says red ink will dry up by 2015. That’s also, as it happens, the year of the next scheduled election. Will Flaherty run again? He’s been the MP for the Ontario riding of Whitby-Oshawa since 2006. He’s also the minister responsible for the Greater Toronto Area, which is shaping up as the key battleground for the next campaign. JG

28: Pierre Poilievre

|

His ascension to cabinet might have turned the stomachs of his critics, but if politics is war, Poilievre had proven himself on the battlefield of question period as a capable and eager combatant. And so, who better to handle the fraught and perilous file of democratic reform? Harper’s Senate reform agenda is now in the hands of the Supreme Court, and a verdict that is unfavourable to the government will only complicate matters. Meanwhile, promised reforms to Canada’s election laws are long overdue. Someone well-practised in fending off criticism and doubt is perhaps exactly what the Prime Minister needed here. AW

His ascension to cabinet might have turned the stomachs of his critics, but if politics is war, Poilievre had proven himself on the battlefield of question period as a capable and eager combatant. And so, who better to handle the fraught and perilous file of democratic reform? Harper’s Senate reform agenda is now in the hands of the Supreme Court, and a verdict that is unfavourable to the government will only complicate matters. Meanwhile, promised reforms to Canada’s election laws are long overdue. Someone well-practised in fending off criticism and doubt is perhaps exactly what the Prime Minister needed here. AW

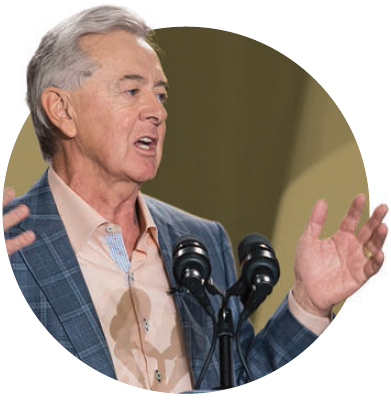

29: Preston Manning

|

In U.S. Republican circles, insiders have long differentiated between the “party,” which seeks to win elections, and the “movement,” which promotes an ideology. When it has come to Canadian conservatism, drawing that line has always been somewhat tricky. But the founder and former leader of the Reform party has made it easier through his Calgary-based Manning Centre for Building Democracy. The centre’s annual networking conference in Ottawa has become a rallying point for true believers—and the Conservative politicians who seek their support. Manning’s own speeches and op-eds about democratic reform and free markets make him a sort of activist elder statesman. He’s held in awe by next-generation power figures like Industry Minister James Moore. JG

In U.S. Republican circles, insiders have long differentiated between the “party,” which seeks to win elections, and the “movement,” which promotes an ideology. When it has come to Canadian conservatism, drawing that line has always been somewhat tricky. But the founder and former leader of the Reform party has made it easier through his Calgary-based Manning Centre for Building Democracy. The centre’s annual networking conference in Ottawa has become a rallying point for true believers—and the Conservative politicians who seek their support. Manning’s own speeches and op-eds about democratic reform and free markets make him a sort of activist elder statesman. He’s held in awe by next-generation power figures like Industry Minister James Moore. JG

30: Jean-François Lisée

|

Back in the dark days of the 1995 referendum Lisée was a speechwriter for Jacques Parizeau, but was quick to distance himself from the then-PQ premier’s “money and the ethnic vote” rant on the evening of defeat. But time has brought Lisée around to at least part of what Parizeau was getting at. Premier Pauline Marois’s bid to stop public servants from wearing obvious religious symbols flows from ideas Lisée hatched about the necessity of the PQ positioning itself as the ultimate defender of Québécois identity. And beyond the polarizing charter, Lisée’s view might just be the most powerful defining set of ideas in the latest variation on separatist doctrine. JG

31: Alison Redford

|

| The Alberta premier made peace (sort of) with B.C.’s Christy Clark; they jointly appointed officials to try to settle their pipeline differences at July’s Council of the Federation meeting. Then in November the two premiers reached a framework agreement moving them a small step closer to a deal on the Northern Gateway pipeline from the oil sands to B.C.’s coast. Redford has taken her pro-Keystone position to Washington several times, making the case for the pipeline to think tanks, State Department officials and politicians. JG |

32: Stephen Poloz

|

The Bank of Canada’s new governor takes over from the biggest star the central bank has ever created, or is ever likely to—Mark Carney, who hopped the Atlantic to take over the Bank of England. But if Poloz can’t hope to match Carney’s star power, economic events might well conspire to force him to take more controversial action. Carney ushered in a prolonged period of holding pat with rock-bottom interest rates, but private sector economists expect that to end sometime next year. If those predictions prove true, Poloz might have the thankless task of reminding Canadian consumers and businesses that rates must sometime rise. Carney’s power rested largely on his charisma. Poloz’s could end up being a function of tough action. JG

33: Michael Ferguson

|

The proposed purchase of the F-35 fighter jet was already a heavily contested file for the government—its price tag the subject of doubt for the opposition and strident rhetoric from the Conservative side—but it didn’t become a fully realized problem until the new auditor general rendered his verdict. Ferguson’s report in April 2012 compelled the Conservatives to completely reposition themselves on the issue of replacing Canada’s aging fleet of CF-18s, and re-evaluate their options. Now Ferguson has turned his attention to the government’s shipbuilding procurement, and sometime after that will come the results of an audit of Senate expenses. He might still be living in the shadow of his predecessor, Sheila Fraser, but Ferguson has already left one mark on Parliament Hill and he might be about to leave a few more. And not only must the government be conscious of what his Senate review might find, so, too, must the entire upper chamber, at a time when the Senate’s existence is already hanging in the balance. AW