The powerful legacy of Canadian running legend Tom Longboat

He was accused of being lazy and troublesome. Yet the young runner overcame racism to win the Boston Marathon

Share

As he pushed through the final two miles of the Boston Marathon, Will Winnie heard a voice in the crowd cheer out the name that he’d written in big letters down his arm.

“Longboat!”

To that point Winnie’s mind had been set on simply finishing the gruelling run. But the mention of his great-grandfather’s name filled him with emotion, and tears joined the sweat streaming down his face.

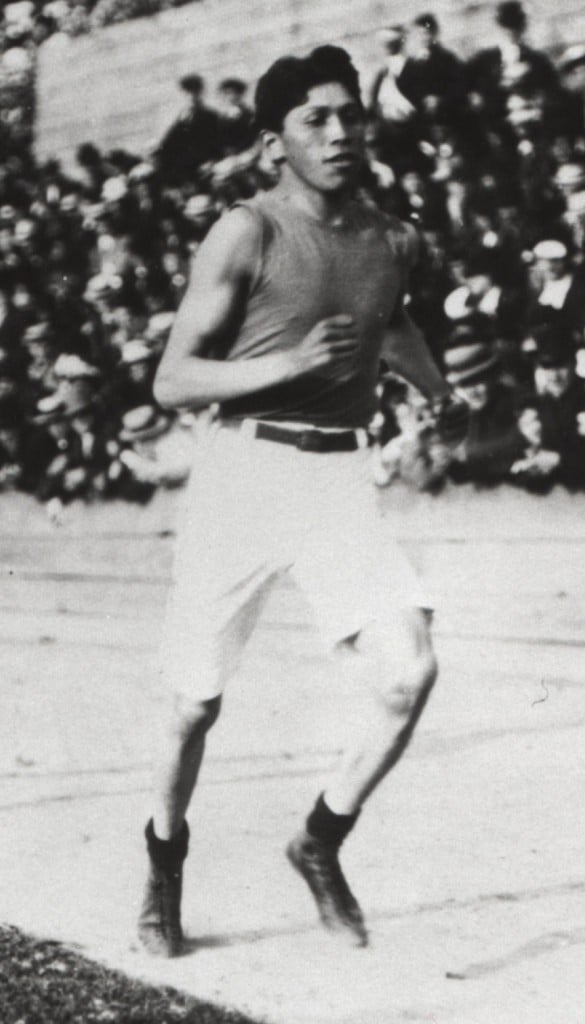

Winnie thought about 19-year-old Tom Longboat on the last stretch of his record-breaking Boston Marathon run in 1907. He wondered what it must have felt like to hear the crowd shout his name as he made history.

“I broke down and had myself a good cry,” Winnie says. “It was overwhelming.”

Winnie was invited to run in 2015 as part of a celebration of great Indigenous runners in Boston Marathon history, such as Longboat, Andrew Sockalexis and Ellison Brown. He’d started training back home in Buffalo only a few months earlier, but those runs took him by the house of his grandmother and Longboat’s first child, Phyllis Winnie, who is now 97 years old. She’d come outside to cheer her grandson on as he passed by.

[widgets_on_pages id=98]

Growing up, there wasn’t much table talk in his family home about Longboat’s experience as a world-famous runner, Winnie says. When his grandmother told him stories about her father, they were always about the man, not the legend. And when there was talk of his accomplishments, they often carried sadness for the mistreatment he faced despite his achievements. Longboat had accomplished remarkable things, but the world he lived in wasn’t prepared to properly honour him for it.

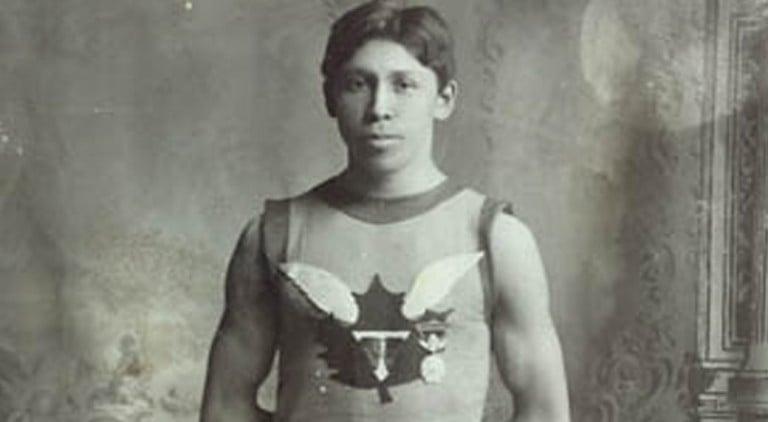

The Onondaga runner grew up on Six Nations of the Grand River reserve near Brantford, Ont., where he was made to attend a residential school when he was 12. Just before his 18th birthday, in 1905, he ran his first long-distance race in Caledonia and never looked back. He won the Boston Marathon just two years later and went on to become one of the most accomplished professional runners of his era.

But Longboat’s individual successes were presented by media at the time as having happened despite his character, not because of it. His work ethic was criticized. His preferred training regimen, which involved taking exceptionally long walks, was viewed as lazy despite being well ahead of its time. Disagreements with his trainers were framed as insubordination to white authority. Later in his career, he was even accused of being a troublesome drunk.

The media repeated these narratives through the years while simultaneously ignoring the voice of the person they were about. As a result, there isn’t much of Longboat’s experience that we know today from his own point of view, says Dr. Janice Forsyth, an associate professor of kinesiology at Western University and a member of the board of directors for the Aboriginal Sport Circle, which seeks to create accessible and equitable sport and recreation opportunities for Indigenous peoples.

“It’s not so much that Tom Longboat didn’t have the opportunity. He probably talked to [reporters] at some level about what was going on,” says Forsyth. “But they chose not to [write it] because they didn’t think it was important.”

Despite the negative framing that surrounded newspaper stories about Longboat, his legacy endured as an inspiration to countless other Indigenous athletes. Alwyn Morris, who won gold and silver medals as a kayaker at the Los Angeles Olympics in 1984, learned about Longboat while growing up in Kahnawake, a Mohawk First Nation near Montreal.

“He was a trailblazer,” says Morris, now the president of the Aboriginal Sport Circle. “In his day, there weren’t very many Indigenous athletes competing at any level [in] what would be called mainstream [sports]. He made incredible inroads.”

When Morris was 12 years old he found a bronze medallion in a drawer at his grandparents’ house. It was the Tom Longboat Award, which honours Indigenous athletes across Canada. It belonged to his uncle, Marvin Morris, a renowned lacrosse player. Morris set out to follow in his uncle’s footsteps, and went on to win the Longboat award twice — to go along with his two Olympic medals.

Today, Longboat’s story continues to inspire a new generation of Indigenous athletes. The annual Tom Longboat Run takes place every June 4 — Tom Longboat Day — on Six Nations land near Brantford, Ont. Each year hundreds of people of all ages run, walk and bike in the event intended to promote athletics and healthy living. At the event, Longboat’s story and legacy are proudly shared. His perseverance in the face of oppression and racism remains an important message for Indigenous youth, says Cindy Martin, the Traditional Wellness Coordinator for Six Nations Health Services.

“There’s been a tremendous effort to keep people in mind of our heroes and to look at the legacies that have been pathways for other athletes to follow behind,” says Martin, who is Longboat’s great-niece. “And not just for people in Six Nations, but for Native people across the country.”

Over the years, Will Winnie says he had lost touch with his great-grandfather’s legacy. But running in the Boston Marathon rekindled his desire to connect with his past. He embraced his wife and kids after he crossed the finish line, and then he called his grandmother.

“It was really emotional,” he says. “She thanked me for running. It was a nice moment.”

Winnie clocked in three hours slower than the record 2:24:24 time his great-grandfather set on the old 24.5-mile course back in 1907. But he felt that much closer to the footsteps laid before him as Longboat’s legacy continues its long run through history.