The unsettling case of Dr. Ngola, the RCMP and the New Brunswick government

Craig Offman: Fifty pages of emails, memos and handwritten notes offer details into a troubled investigation into a COVID-19 outbreak

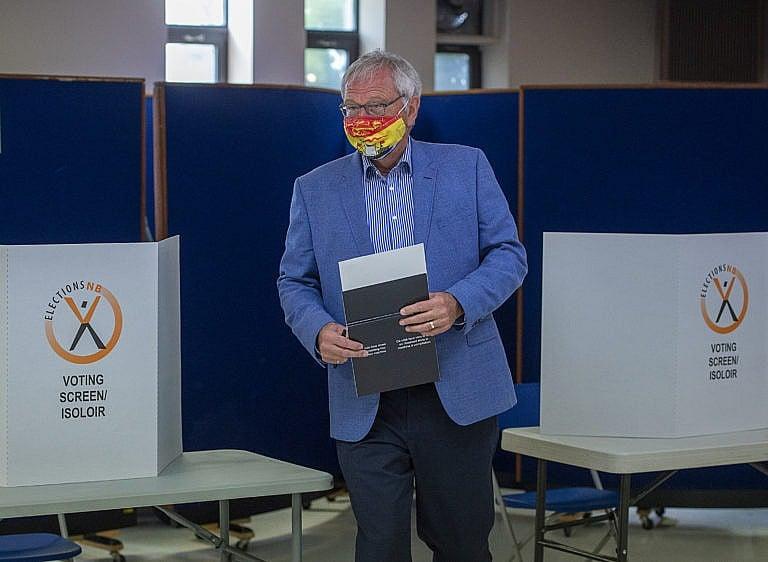

Premier Blaine Higgs heads to cast his vote in the New Brunswick provincial election in Quispamsis, N.B. on Sept. 14, 2020 (CP/Andrew Vaughan)

Share

Last spring, Jean Robert Ngola Monzinga was arguably Canada’s most infamous COVID spreader, a small-town doctor whom authorities singled out as patient zero during an outbreak that infected 41 people and took two lives in northern New Brunswick.

The initial suspicion, it seemed, was based on Dr. Ngola’s failure to self-isolate after a brief trip from his hometown at the time, Campbellton, a town on the Quebec border. In May, the RCMP opened a criminal investigation against him, but in July, it emerged that the force had quietly dropped the case. By then, however, the accusation had turned the physician’s life upside down. Fearing for his safety after death threats and racist abuse, Ngola (the surname he goes by) moved across the Restigouche River to Pointe-á-la-Croix, Que. Now, only one legal hurdle remains. Rather than facing criminal charges for negligence, the 51-year-old physician will go on trial this June for violating the province’s Emergency Measures Act for his failure to quarantine.

His lawyers have insisted that Dr. Ngola was following the same protocol as other doctors travelling back and forth over the provincial borders, and that he only wanted to get back to work. They previously have pointed out that of all the medical workers going in and out of New Brunswick at the time—some of whom also tested positive—only the racialized one was singled out. (They would not provide comment for this story.)

But a key question remains: on what basis did the authorities suspect him of infecting others? Crown disclosures provided to Ngola’s defence lawyers and filed in provincial court—50 pages of emails, memos and handwritten notes from the RCMP and government officials, among others—offer unsettling revelations.

Namely, when Dr. Ngola was singled out, documents indicate there was no official complaint against him. Instead, provincial officials and the RCMP worked together to find a complainant after New Brunswick Premier Blaine Higgs identified a man fitting Dr. Ngola’s description as patient zero at a press conference.

“It was the Premier’s Office and the RCMP who took proactive and highly unorthodox means in a concerted effort to lay blame on the Applicant after his name had been smeared through social media and eventually through traditional media outlets,” Dr. Ngola’s lawyers allege in their notice of application.

The RCMP and the Premier’s Office declined comment.

Roger J. Ouellette, a public policy professor at the Université de Moncton, finds the alleged cooperation between the provincial government and the police troubling. “It’s really important to have some separation,” said Ouellette, who said he pored through the defence’s findings.

In Ouellette’s view, the June trial will be as much about Dr. Ngola as it will be about Premier Higgs and his government.

The trouble began for Dr. Ngola in mid-May. A physician trained in Congo, Belgium, and at Laval University, he has said he drove across the provincial border to suburban Montreal to pick up his four-year-old daughter. She needed care while her mother—his ex-wife—flew to Africa for a funeral. On the way back, he met with medical colleagues near Trois-Rivières before crossing into Campbellton.

Emergency regulations forced most travellers to self-isolate after returning to the province. Doctors, however, operated in a foggier realm. His lawyers have insisted there weren’t a lot of them, and the few who were practicing in that borderline area of New Brunswick travelled frequently back and forth across the border. If all medical workers quarantined, there would be a consequential shortage. Working within these vague constraints, Dr. Ngola said that he checked in with provincial health officials, who told him that as an essential worker, he could return to his practice—provided he didn’t believe he had come into contact with the virus. (Dr. Ngola has previously said he doesn’t have recordings but has mobile-phone logs to verify his claim.)

Dr. Ngola wasn’t the only front-line worker to opt against self-isolation. The CEO of the company that once employed Dr. Ngola, Vitalité Health Network, told the CBC in an interview that 22 doctors from outside New Brunswick also hadn’t fully self-isolated for 14 days after travelling during the pandemic.

Asymptomatic, Dr. Ngola returned to his patients.

Around that time, New Brunswick was relatively successful at containing the spread of COVID-19, a key part of the Atlantic Bubble: it had two active cases and several transmissions. But two weeks later, this particular bubble burst. Premier Higgs and the province’s chief medical officer, Jennifer Russell, announced an outbreak, the so-called Campbellton Cluster. Contract-tracing, she said, determined that the infection was carried in from another province.

On May 27, Dr. Ngola became a marked man. At around 11 a.m., he learned that he had tested positive for the virus, and within an hour, details about his health were leaked on social media. At a 2:30 p.m. press conference, the province’s premier blamed the COVID-19 cases on an irresponsible medical worker who failed to quarantine after travelling out of the province. With confidential information about Dr. Ngola mysteriously leaked and posted on the internet, it wasn’t difficult to piece together who the premier was pointing the finger at. (Premier Higgs has said he never identified Dr. Ngola).

By the end of the day, Vitalité Health Network suspended Dr. Ngola without pay. Death threats and racist taunts piled up. He said he had to disconnect his phone: people were stalking him, calling him a refugee, telling him to go back to Africa. His home address was also publicly made available. The following day, the premier informed journalists that the RCMP was investigating the unnamed—yet identifiable—medical worker.

So what triggered the investigation against Ngola, specifically? A complaint? Or the contract tracing Russell had referenced? If there really was a patient zero, no one in authority ever publicly identified them.

RCMP memos supplied to Dr. Ngola’s defence team suggest that on May 28, when Premier Higgs announced that Dr. Ngola was the subject of a criminal investigation, no such inquiry was underway. Nor was there a complainant that would have triggered it. Notes instead indicate that Mounties and the provincial government worked in tandem to bring a complainant onboard.

Internal RCMP documents indicate that Jean-Marc Paré, acting officer in charge of the serious crime section at the RCMP’s “J” Division in Fredericton, seemed taken aback by the announcement. It was his team, after all, that would have had to initiate the case.

“I noticed the Premier mentioned in the media that the RCMP was taking over the investigation, at that time none of us were aware we were getting involved,” wrote Staff Sgt. Paré at 9:43 a.m. “There are already a couple of issues…the first thing being we don’t know who our complainant is.”

Another Mountie out of Bathurst working on the case, Cpl. Jonathan Simard, shared the same concern around the same time. “Who is the complainant… we must find a complainant ..we must verify with upper management,” he said in his notes, written in French.

According to the documents submitted by Dr. Ngola’s defence team, one candidate was Dr. Mariane Pâquet, a medical officer in charge of health in the Campbellton region. But Dr. Pâquet repeatedly refused to engage with the RCMP. “Last night I spoke with the Chief Regional medical officer for that area, Marianne [sic] Paquet, and she wouldn’t talk to me due to privacy issues,” Paré wrote in an email.

Documents show that Pâquet continued to stonewall the police throughout their quest for a complainant, saying that the police needed a warrant and that Dr. Ngola’s safety was at risk.

At 10 a.m., “J” Division notified the RCMP’s Ottawa headquarters that it was actively involved in the case, looking for possible charges of criminal negligence. Ultimately, the force assigned 21 members to the case.

In the meantime, though, Paré’s quandary remained. There was no complainant.

Toward the end of the day, Cpl. Simard’s notes indicate that RCMP was still searching for one. At 4:05 p.m., Simard noted in French that he called Jacques Babin, Chief and Executive Director of the province’s Department of Justice and Public Safety. Babin told Simard that he had met with his deputy, Mike Comeau, and Premier Higgs. During that meeting, Babin said, the group decided to involve the RCMP formally. They also decided that Babin should be the official complainant, a proposal that was soon dropped. The notes don’t say why.

(The Department of of Justice and Public Safety declined a request to comment.)

At 5:28 p.m., Andrew Easton, director of security and emergencies in Babin’s department, contacted Gilles Lanteigne, the outgoing CEO of Vitalité, the health company that two days earlier suspended Ngola. (Lanteigne would retire in October.) “Police services need a complaint before they can begin an investigation,” Easton wrote in an email in French. “As you have personal knowledge of the issue that affect our health care system, you may want to advise the RCMP members who are copied on this email of your concerns.”

Nine minutes later, Constable Martin Primeau of the Major Crimes Unit also reached Lanteigne. “The premier was angry and demanded an inquest because of the grave consequences of the doctor’s actions,” he wrote in French. “As discussed today, an official letter requesting an RCMP investigation would be required in order to continue this delicate matter.”

The RCMP’s Simard subsequently emailed Easton, informing him that Lanteigne would file a complaint.

Even still, the RCMP had to square the backdating issue: How to reconcile the Premier’s May 28 announcement of an investigation with the complaint’s timing, which came two days later?

On June 2, RCMP Cpl and spokesperson Jullie Rogers-Marsh wrote to Jean-Marc Paré, “ I think we go with the date we got the complaint [,] so May 30,” she suggested.

In his response, however, Paré sounded hesitant. “This sounds good, the complaint was officially received on May 30th by Vitalité,” he wrote. “However I believe Premier Higgs announced the RCMP were investigating on Thursday May 28…..not sure how we deal with that.”

That, and maybe a few other things.