Not your usual War of 1812 at the Canadian War Museum

Eschewing triumphalism, the exhibit is a narrative of four wars — or rather, four perspectives of the same war

Share

For a sneak peak of the exhibit, check out our photo gallery at the bottom of the page.

The easiest course of action for the Canadian War Museum to take when planning its War of 1812 exhibition would have been to create a grand and triumphalist narrative about the struggle to save Canada. This is how the conflict is widely understood, and how it will be celebrated in numerous government-funded commemorations.

Instead, a visitor entering the exhibition is introduced not to one war, but four—or rather four perspectives on the same war. There is a central hub, and from there, like spokes on a wheel, are four mini-exhibitions that show how the war was viewed by its major combatants: the Canadians (including Aboriginal Canadians), the British, the Americans, and the Native Americans who sided with the Canadians and British.

“If you’re a Canadian, the Americans invaded, and we pushed them back, and we evolved into an independent country. So as far as we’re concerned, it’s hardly worth saying that Canada won,” says exhibition curator Peter MacLeod, the museum’s pre-Confederation historian. “But the Americans have their own take on it. They went to war with the British Empire, the most powerful empire in the world. And they fought them to a draw. They forced them to respect American independence and American sovereignty. So as far as the Americans are concerned, it’s just as obvious that they won.”

To the British, says MacLeod, the conflict in North America was a sideshow to the more important war against Napoleon in Europe. They invested the weapons and men they could spare, and the Royal Navy blockaded American ports, but defending Canada was of secondary importance.

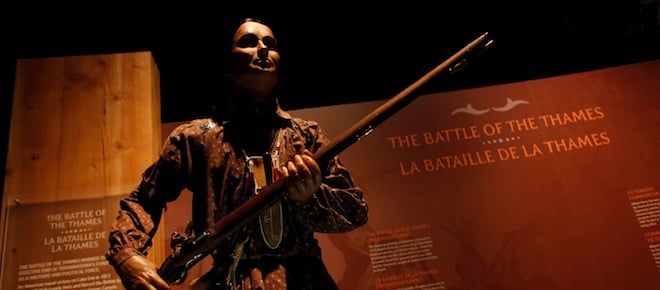

For Native Americans, it was an existential fight. “Here is a chance presented to us,” the Shawnee leader Tecumseh said, “a chance such as will never occur again, for us Indians of North America to form ourselves into a great combination and cast our lot with the British in this war.”

Tecumseh’s coalition of Native American tribes believed that by aligning themselves with the British, they might stop American expansionism. “This is the last war where they have a serious chance to roll back the American frontier,” says MacLeod. “And it’s the last war where they have a European ally on their side. After this they’re facing the United States on their own, and the Americans basically roll straight to the Pacific.”

Though the Native Americans on the British side failed to stop American colonization of their homeland, they established an enduring relationship with the British Crown. Five decades later, Dakota Indians fleeing the United States sought refuge in Canada. Some carried medals that had been awarded to them by the British for service during the War of 1812 as evidence of friendship and mutual obligation. Their descendants are the Whitecap Dakota First Nation in Saskatchewan.

About half the artifacts come from the war museum’s collection or from the Canadian Museum of Civilization. There is Sir Isaac Brock’s red tunic, complete with a bullet hole from the shot that killed him during the battle of Queenston Heights, a British and Canadian victory against an attempted American invasion across the Niagara River.

A statue of a British imperial lion, looted by American raiders from the legislative assembly at York before they torched the place in 1813, stands—appropriately enough—opposite a charred piece of wood from the American White House, which the British burned the following year. These are on loan from the United States Naval Academy and the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. One of the most interesting displays is a model canoe with six paddlers made by an Odawa veteran of the War of 1812. Each paddler is made in the image of a native warrior or chief who fought on the British and Canadian side of the conflict. It seems today a touching testament to the bonds formed from war.

Other artifacts reflect its pathos. There is an ornamental metal marker that members of American patriotic societies placed on the graves of American 1812 veterans in the middle of the 19th century. “It speaks,” says MacLeod, “to the universal experience of death and suffering in war.”

[gallery2 exclude=”266024″]