The way we talk about opioid addiction hasn’t really changed

On ‘Janey Canuck,’ and what history tells us about dealing with the opioid crisis plaguing places like British Columbia

Share

Christine Sismondo’s Canadian Moments column looks at what history can teach us about a current moment in Canadian news, politics, or culture. Read more of her columns here.

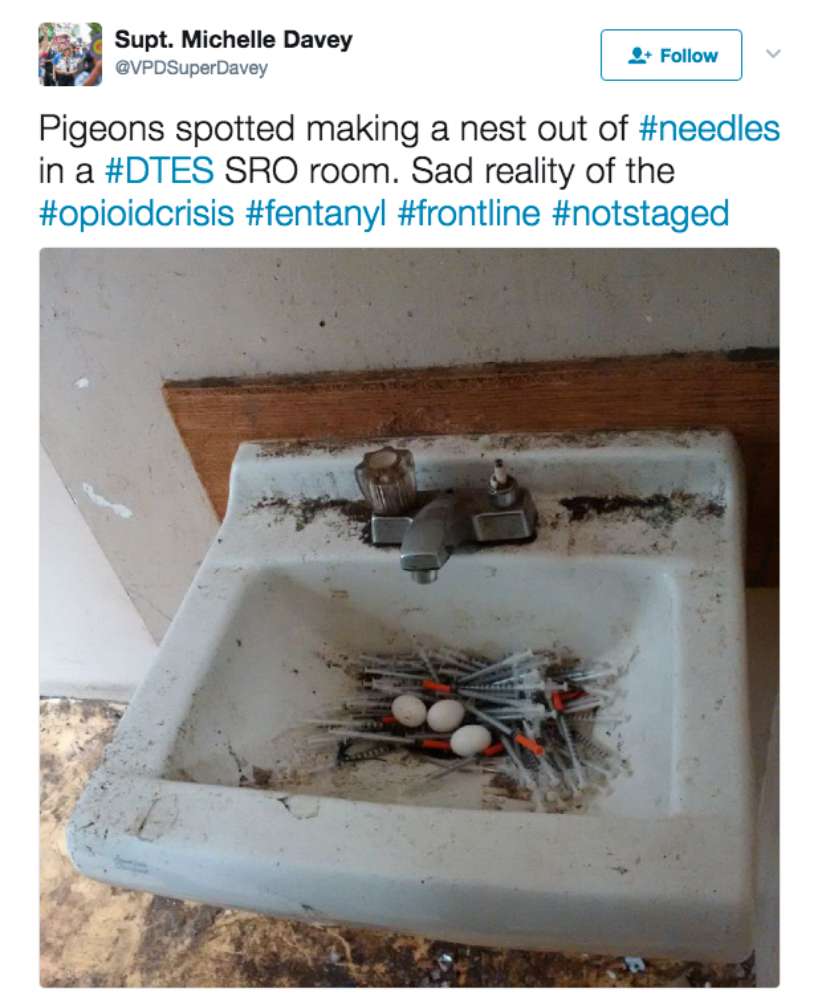

Last week, a photo of a pigeon’s nest in a filthy sink of a Vancouver single-room occupancy hotel became international news, picked up by Buzzfeed, the Independent and the South China Morning News. The nest, three eggs included, was made entirely of discarded drug needles. It was a potent image, for sure, since it evoked ideas of nature corrupted within a dystopian urban hellscape where the building blocks of nature had been replaced with old hypodermics.

It was also more than a little suspicious-looking. Ornithologists were quick to jump in and say that, even aside from the needles in the place of twigs, it didn’t look like any pigeon’s nest they’d ever seen. True or not, it managed to capture the public’s attention in a way that other news has not. Vancouver experienced 15 opioid deaths that same week, for example, and things are expected to degenerate further, since there are reports of a new, even more potent and dangerous “heroin” on the streets, this one spiked with fentanyl, carfentanil and a new synthetic opioid, U-47700; it is responsible for even more overdoses.

But images and sordid stories have long moved people more than stats—even as of the first major opiate drug panic in Canada, circa early 20th century. Reformer Emily Murphy, a.k.a. “Janey Canuck,” published many tales of sorrow and degradation—especially the ones involving white women from “good families”—in her 1922 book, The Black Candle. Since Murphy was the first woman magistrate in the entire British Empire, it’s reasonable to assume many of the stories were related faithfully as they were told to her, either in her role on the bench or in working with police. But some of her sources sound less solid than others. Like this one: “In Vancouver, it is related recently that a woman who was an inveterate drug-user injected morphine into her baby whenever it cried or was troublesome. When the infant died, its body was found to be terribly punctured by the hypodermic needle.”

That was from her chapter on the hypodermic needle and the damage done, some of which was excerpted in a Maclean’s article, “‘Joy Shots’ That Lead to Hell,” in which she argued that needle technology had upped the stakes. The opium dens, full of smokers and their pipes, were practically quaint relics compared with the new generation of “prodders” or “rats,” who used needles to administer a more potent version of opium, morphine, making the addiction yet more dangerous. “If the Chinese introduced opium to this continent, America has paid them back a thousand-fold in very evil coin by teaching them the use of the hypodermic needle,” Murphy wrote.

Of course, Janey Canuck wasn’t going to let the Chinese off the hook entirely. Her book is saturated with xenophobia and racist views on South Asians, East Asians and African-Canadians, the kind that were in line with her general white supremacist views, supported by scientific racism. She was concerned about feeble-minded girls and, in her own sentencing as a judge, would demonstrate a penchant for harsh penalties.

Because of her law-and-order mentality, some people have argued that Murphy’s writings led to the criminalization of marijuana in 1923 and paved the way for the 1929 Narcotic and Opium Act, which threw the book at the prodders and their suppliers and, simultaneously, gave police more power and freedom to enforce the drug laws. Neither argument, though, holds up to scrutiny. Sure, Murphy had a hand in shaping public opinion, but the idea that a woman reformer’s urgent polemics led to widespread societal change is wildly optimistic about the powers of both the pen and individual actors—especially when those actors are women. Opium had been the source of public debate and concern for almost 50 years before Murphy was appointed to the bench and the subject of a restrictive law in 1908 that was firmly connected to anxieties over contagion, moral decay and racial degradation. It was, in fact, an arm of the anti-Asian “yellow peril” of that era.

Before we write off Janey Canuck though (for any of the many reasons she should never appear on a $10 bill), it’s worthwhile to note that she had a more nuanced understanding of the problem than is often remembered. On top of the fact that her analysis of the problem went beyond individual morality and included technological advances, she also wrote about the era’s social upheaval following the Great War and was especially sympathetic to veterans addicted to drugs they had used to endure mental and physical trauma.

Murphy saw it as more than a moral failure, spreading blame around to systemic problems, including the medical community, which Murphy accused of being reckless with prescriptions, and failing in its role as primary steward of the opium trade since 1908, when the law restricted opium to medicinal use. Prior to that, it had been left to business interests, which were considerable, given that Victoria had been the biggest opium processing plant in North America. As Brock University history professor Dan Malleck points out in his book, When Good Drugs Go Bad: Opium, Medicine and Canada’s Drug Laws, it was a complicated situation, mainly because opioids aren’t just bad drugs—they’re also really good drugs, essential for humane medical treatment.

Medical and legal solutions, then, are there to help us negotiate this tension. They have recently failed us—in remarkably similar ways to the ones that failed in the early twentieth century—since the fentanyl crisis can be traced back to a lucrative patent and the rampant over-prescription of new opioids by doctors, egged on by reps from the pharmaceutical industry. Most people became addicted because of legitimately prescribed pills and, now that the ink has run dry, seek illegal sources, which are far more potent and dangerous.

Going forward, these legal and medical mechanisms will need reform and, in the meantime, many people will advocate for some form of safe, legal opioid, which sounds like a good first step, given the dangers of synthetic versions now on the market. The recent Canada-wide Good Samaritan Overdose Act, which encourages people to call 911 in the case of an overdose without fear of legal repercussions, is a step in the right direction.

As we make these changes though, it’ll be prudent to pay closer attention to the human side of Janey Canuck’s writings, in which she sympathized with mothers and veterans and acknowledged that people were drawn to opium and morphine to deal with real pain, much of it resulting from social upheaval. We’ll make no dent in the problem if we don’t.

And judging from the reaction to the viral photograph of the alleged pigeon’s nest in the sink, we’re not exactly on track to do that, since, surely, one of the worst aspects of that image was that the photo was taken by the police department’s homeless outreach co-ordinator in an (admittedly abandoned) room in a Single Room Occupancy facility.

What does the rest of that facility look like? Even tough-on-crime, xenophobic, eugenics-proponent Judge Janey Canuck would want to know that. And she would also know that no serious progress can be made on drug reform without addressing inequality, pain and hopelessness, too.