Unplugged: Remembering the blackout, 10 years later

From the Maclean’s archives

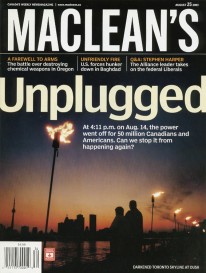

The CN Tower is silhouetted against the setting sun, as Toronto faced a massive power outage, August 14, 2003. (Andrew Wallace/Reuters)

Share

Today marks the ten-year anniversary of a massive blackout that left parts of Canada and the eastern United States in darkness. As officials ponder the security of North America’s power grid a decade after the power failure, here’s our cover story on how the blackout unfolded: ‘Unplugged,’ first published in Maclean’s August 25, 2003.

IT TOOK just nine seconds to turn the clock back a century. A voltage fluctuation in some Ohio transmission lines. Then, at 4:11 p.m. on a muggy August Thursday, a faster-than-you-can-blink reversal in the flow of current, suddenly sucking away a city’s worth of power from the eastern half of the continent. Computerized safety systems kicked in and 100 generating stations across Ontario and seven U.S. states were knocked off-line like tumbling dominoes. The lights went out, air conditioners stopped humming, television and radio stations fell silent, subways, streetcars, and elevators shuddered to a halt. Fifty million people looked at their watches, flipped suddenly useless power switches, and began a long, hot wait for someone to restore the natural order.

Not a surprise, exactly. We’ve all experienced blackouts before. And in power-starved Ontario, where 10 million citizens found themselves unplugged, the experts had long been predicting summer shortages. But as the minutes ticked by and the scope of the problem became clear — no electricity from Ottawa to Windsor, major American cities like New York, Detroit and Cleveland also at a standstill — there was a kernel of dread. In Manhattan, with the second anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks looming, that fear quickly came to the surface. “The first thing I thought was, ‘Oh my God, this is another terrorist attack,’ ” says Henry Flesh, who works in the 30th-floor offices of a large publishing company. “We looked out on the streets, saw a lot of people outside, and couldn’t figure out what was going on. We didn’t have a radio with batteries, and some people got pretty scared. Some were joking and I was trying to joke, too, but underneath it all I thought, ‘Geez, we could be about to be blown up in a few minutes.’ ”

In Toronto, thousands found themselves trapped in elevators and the city’s subway. It took fire and transit officials hours to free them all. “The car became pretty sweaty, and after about 20 minutes it got really hot and very hard to breathe. There were people who were running back and forth between the cars — I think they might have been claustrophobic,” says Adam Durbin, a 22-year-old student, who was heading home when the blackout hit. “I just wanted to get the hell off the train. Nobody on board was really talking about what had happened because nobody knew anything. We were all just concentrating on not passing out because it was so hot down there.”

Above the surface, the scene was no less chaotic. Sidewalks overflowed with transit users forced to take to shank’s pony. With all of the city’s 1,773 traffic lights out of service, and streetcars stopped dead in the tracks, vehicles gridlocked within minutes, despite the best efforts of good Samaritan citizens directing traffic. TTC worker Malcolm MacPherson donned a reflective vest and leapt into action at one busy intersection. “Amazingly, the drivers were obeying me,” he says. “They’d beep their horns and some of them handed me bottles of water.”

Above the surface, the scene was no less chaotic. Sidewalks overflowed with transit users forced to take to shank’s pony. With all of the city’s 1,773 traffic lights out of service, and streetcars stopped dead in the tracks, vehicles gridlocked within minutes, despite the best efforts of good Samaritan citizens directing traffic. TTC worker Malcolm MacPherson donned a reflective vest and leapt into action at one busy intersection. “Amazingly, the drivers were obeying me,” he says. “They’d beep their horns and some of them handed me bottles of water.”

As the afternoon turned to evening, emergency officials across the blackout zone braced for the worst, but were faced with remarkably few problems. There were crimes of opportunity — small-scale larceny in parts of Brooklyn, N.Y., a jewellery store robbery on Ottawa’s Sparks Street, just 30 minutes after the power went off, 23 cases of looting in the capital, and 208 break-and-enters in Toronto, about six times the usual nightly total — but nothing compared to infamous blackouts past. In Detroit, officials ordered an 11 p.m. curfew for teenagers and delivered blunt warnings of hefty jail terms for troublemakers: “Before you pick up a brick and throw it, before you tip over a car, before you take a TV, you better ask yourself, is this worth 10 years of my life?” the local prosecutor told a news conference. But there were few arrests. The biggest challenge came in Cleveland, where 1.5 million people were left without drinking water when backup power went down at local treatment plants. The National Guard was quickly pressed into service to distribute more that 6.3 million litres to thirsty residents.

Among the most affected were travellers. The blackouts closed or partially shut down 12 major airports in Canada and the United States. Domestic flights were cancelled, and incoming international planes diverted. Toronto’s Pearson International not only had to contend with power outages, but the complete collapse of Air Canada’s computerized control centre. The struggling airline ended up cancelling more than 500 flights, leaving thousands stranded in terminals around the world. Rick and Helen Bailey, travelling home to Edmonton after visiting family in St. John’s, Nfld., were stuck at Pearson for more than 48 hours. “We were on a flight that was supposed to leave Newfoundland at 9 a.m., but the plane blew a hydraulic part so they flew a new one in,” says Rick. The couple got to Toronto just as the lights went out. Their connecting flight was cancelled, and like thousands of others, they were left to fend for themselves. “We said what about hotels — they told us we’re on our own.” The Baileys bedded down in the terminal. “I didn’t even want to guess where our suitcases were,” says Rick.

Hospital patients, people with debilitating illnesses and the disabled also faced more discomfort than most, but health institutions rose — occasionally heroically — to the challenge. In Hamilton, city employees worked frantically through the first hours of the crisis to route emergency power to the Regional Cancer Centre, so that two leukemia patients could complete radiation treatments before life-saving stem cell transplants.

But mostly, people just made do. In many affected communities a carnival atmosphere took over. People made the rounds of neighbours to chat, took to backyards to barbecue and admire the stars, or found refuge in candlelit bars and restaurants. Toronto’s Brent Turnbull and his fiancée, Kelly Jones, filled a spill-proof camping bottle with wine, hopped on their bikes and cycled around the city. On the journey they discovered an impromptu picnic party with people cooking dinner on propane camping stoves in a park, and an outdoor dance in an alley of a downtown street, where a DJ was spinning records with the aid of a small generator. “You could see the top of the CN Tower and it was so amazing — the moon was on the left and Mars was on the right,” says Turnbull, 34. “When the street lights came on after a few hours, a huge cheer went up and then there was this pregnant pause, and people started saying ‘Turn them back off!’ The magic was gone. But I think that’s what we’ll call it: the perfect night.”

By late Friday night, most American cities had fully restored power, and were already returning to normal — major-league baseball and NFL exhibition games went ahead as scheduled in Cleveland — leaving many Ontarians to wonder why they were still in the dark. In Toronto, where the power situation remained precarious throughout the weekend, and the venerable Canadian National Exhibition was forced to postpone its opening, Premier Ernie Eves warned of rolling blackouts and more trouble ahead. “We don’t have an abundance of power,” he said. “So I encourage industry and commercial and office facilities not to use power you don’t need to use.” The greatest threat, however, might be to Eves and his Tory government, who must call an election in the coming months. Opposition parties are already trying to make them wear the blame for the blackout, just the latest crisis to befall the province’s crumbling and deeply indebted electricity system.

Prime Minister Jean Chrétien and U.S. President George W. Bush have already pledged to set up a joint task force to probe the cause of the blackout and the security of North America’s highly interconnected power grid. “You can’t blame anyone. It happened,” Chrétien said, perhaps wishfully. “Fifty million people have been involved in this problem, and what is great is the people have kept their calm and accepted fate very graciously.”

Critics, however, are already pointing to government policies in both the United States and Canada that have led to less money being spent on refurbishing outdated power infrastructure. “We’re a superpower with a Third World grid. We need a new grid,” said former U.S. energy secretary Bill Richardson, now the governor of New Mexico. Some observers are suggesting that Ontario and the affected states need to radically rethink their systems, given the failure of multiple safety measures that were supposed to keep the lights on, and go back to smaller generating stations that service each local area. After all, this isn’t the first time such widespread failures have blacked out eastern North America. There is even an international body — the North American Electric Reliability Council — charged with preventing such events. Its president, Michehl R. Gent, said he is as confused as everyone else. “If we’ve designed the system for this not to happen, how did it happen?” he told reporters. “I can’t answer that question. I’m embarrassed.” Honest, but not exactly the illuminating response 50 million were hoping for.

– With Amy Cameron, Sharon Dolye-Driedger, Jonathan Durbin and Bob Marshall in Toronto, and Paul Wells in Ottawa

Unplugged: The Numbers

9 seconds: Time it took for the cascade to collapse the grid

50 million: People affected

8: Jurisdictions affected (Ontario and seven states)

2,400 sq. km: Area affected by blackout

One million: Kilometres of high-voltage lines in North America

37: Number of major points where electricity sectors link

10,000: Number of power plants in North America

100: Number shut down in blackout

22: Number of nuclear power plants shut down

50-60 years: Average age of the North American power grid

ONE: Rank, in terms of size, of last week’s blackout

Second largest: 1965 northeast blackout

5,000 megawatts: Size of the latest power swing (mismatch between energy supply and demand)

800 megawatts: Size of power swing of 1965 blackout

30: Percentage increase in demand for power in the U.S. over the last decade

15 per cent: Increase in U.S. capacity

Up to to $100 billion: Estimated cost of modernizing the North American power grid

Nearly 15: Percentage of its power supply Ontario imports

200+: Number of major industries in Ontario asked to shut down temporarily

4-6 hours: Time a refrigerator without power can keep food cool

2 hours: According to Health Canada, length of time after which unrefrigerated, perishable foods should be thrown out