Why it’s so hard to fire bad teachers

From 2009: Most principals would rather hide or transfer incompetent teachers than try to oust them

Share

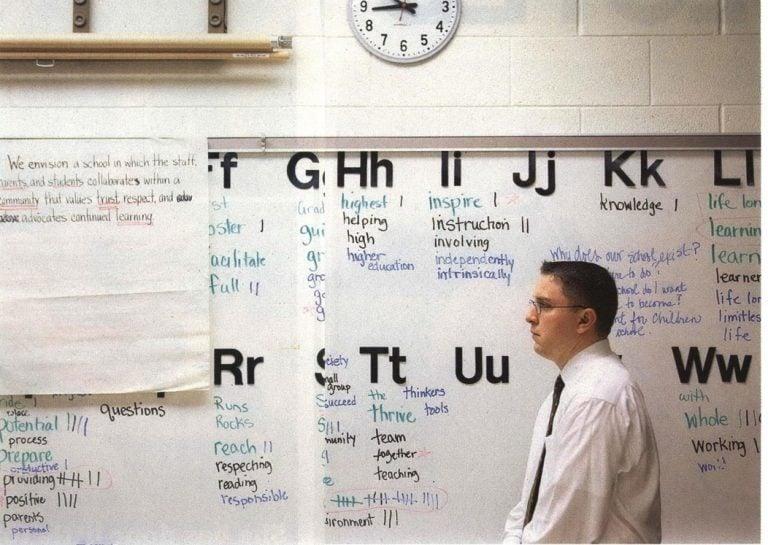

What it took for one Ontario principal to rid her school of an incompetent teacher is a process she’s not fond of revisiting. It began in September 2007, when she inherited a teacher whose performance was already under review. Despite a file thick with evidence of inadequacy, the principal helped draft an “improvement plan”—a requirement in the provincial Education Act—and dipped into school funds to pay for substitutes while the struggling teacher attended workshops. But, says the junior school principal, it soon emerged that there was “a serious, basic problem of not understanding”—which continued even after the teacher knew she was under review. Students shuffled through reading levels without proof of assessment. Parents complained about spelling test words that weren’t sent home. And the teacher submitted grades for computer class when, in fact, her “inability to use technology” meant the monitors “were rarely turned on,” says the principal. Still, it took months of paperwork and meetings with union representatives before she was able to inch even one step closer to dismissal. “It was very upsetting,” she says. “I wouldn’t choose to do it again unless I absolutely had to.”

Inadequate teaching has been shown to contribute to dropout rates, low test scores and a dislike for school. So severe are the implications, says Brendan Menuey, an assistant principal in Virginia, that poor teaching is tantamount to “educational malpractice.” Yet in Canada, teacher incompetence prompts so few administrators to pursue termination that the Ontario principal insisted that not even the name of her school board be published, because it would almost certainly identify her. According to Barrie Bennett, a professor at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, the dismissal process is so onerous, the risk of reprisal from teachers’ unions so great, that “most principals find it’s not worth the effort.” Instead, they approve transfers, or hide struggling teachers where their deficiencies can go unnoticed. The result however, is this: a system that keeps incompetent teachers in the classroom.

The fact that more bad teachers aren’t being fired is “a problem that nobody wants to talk about,” says Menuey, who authored a 2007 study on the subject. Despite research indicating that about five per cent of every workforce is incompetent, he uncovered a truth about his district he describes as “scandalous”: less than one-tenth of one per cent of tenured teachers were being dismissed annually for poor performance. When viewed through this lens, the Canadian numbers are even more damning. Of the roughly 200,000 educators licensed by the Ontario College of Teachers to teach, only 27 have been terminated due to poor performance since 2004—an annual average of just 0.002 per cent. In the past five years, not a single permanent teacher has been dismissed for incompetence in the largest school boards in Montreal and Winnipeg; Saskatoon Public Schools has terminated just one; and in Edmonton Public Schools, says a spokeswoman, “very few if any” have been let go.

While a report of sexual or physical abuse is clearly grounds for disciplinary action (as well as a police investigation), what constitutes teacher incompetence can be somewhat fuzzy. As a teacher, Menuey says he had a colleague who gave “no grades at all.” When filling out report cards, this teacher would ask around to determine what grades each student had earned in other subjects, and “give them the same,” he says. While working for Edmonton Public Schools, Bennett once offered support to a teacher who would ask his unruly students to choose between the classroom and the hall. “Sometimes, I’d come to his classroom and there would be 10, 11 kids out in the hallway,” he says.

In most provinces, teacher incompetence isn’t formally defined. Yet long before termination is even a possibility, principals must document alleged instances of incompetence, often for the better part of a year. “It’s very labour-intensive and time-consuming,” says the Ontario principal. “You have to be meticulous or the union will grieve you.” Although the teacher in this case left before she could be formally fired, the principal says a grievance remains a possibility. But if inadequate teachers are being overlooked, says Frank Bruseker, president of the Alberta Teachers’ Association, it’s not the unions that are to blame. “The school boards and the principals need to step up the plate,” says Bruseker. “To simply say, ‘We’re not doing our job because we’re scared of the unions,’ says to me that they’re abrogating their responsibility. If we’re talking about incompetence, maybe they should be looking in the mirror.”

However, as educators are quick to point out, low dismissal rates don’t necessarily mean that bad teachers aren’t being ushered out of the classroom. In the Halifax Regional School Board (HRSB), where six teachers have been terminated in the last five years for either professional misconduct or incompetence, an additional 33 have resigned or been removed from lists of approved substitutes and those under consideration for future contracts. And according to Mike Christie, director of human resources at the HRSB, “self-screening” is a significant safeguard that these numbers don’t reveal. “Teachers have got a tough crowd in those kids,” says Christie. Many of those who are struggling simply “take themselves out of the profession,” he says.

Still, teachers are well aware that being bad at their jobs will rarely earn them their walking papers. As part of his study, Menuey asked teachers to rank a list of 19 strategies that administrators use to deal with incompetence. They identified “voluntary transfer to another school” as the most prevalent. Dismissal, meanwhile, was ranked 14th. “We all knowingly play this game,” says Menuey. “I believe passionately that we need to get rid of these folks, but I’ll be honest, because of the time and the difficulty in getting what you need, I’m inclined, when [another] principal calls me, to just say, ‘She’s a fabulous teacher.’ ” This practice, dubbed “passing the trash,” is hardly news to Bennett. He says “writing an okay reference letter” to get rid of an incompetent educator is endemic “at all levels. It’s not just teachers in classrooms—it’s principals in schools, it’s central office people too.”

Other strategies are similarly problematic. According to a teacher in Ottawa’s French Catholic board, when one of his colleagues couldn’t cut it this year, the school “purposely gave her the most difficult classroom.” Within months, he says, she “burnt out,” and is currently on medical leave. (Virginia teachers also ranked “increased workload to encourage teacher resignation” above termination.) Oftentimes, Menuey says shuffling inadequate teachers to another class is an attempt to give them students “whose parents won’t pitch a fit”—though these are typically the kids who stand to gain the most from quality instruction. More disconcerting still is something the teachers came up with themselves. The highest ranked write-in tactic on Menuey’s survey: “ignore the problem.”

Not all struggling teachers are beyond help. For some, observing more experienced colleagues or learning to better manage students is all it takes to spark improvement. To that end, many administrators are more than willing to offer every support available, which, in many school boards, is a lot. As Menuey explains, “We believe that all kids can be successful, and we believe that all teachers can be successful.” But in some cases, this culture of acceptance may be blurring the line between effective remediation and a fruitless pursuit. Even the Ontario principal, who says she “had no choice” but to go through with dismissal, expresses a palpable discomfort: “We’re educators. We’re not trained to fire people.” However, when incompetent educators are left to teach, whether in a roomful of difficult Grade 5 students, or hidden in the school’s art department, it’s kids who pay the ultimate price.