Why it’s time to legalize marijuana

After decades of wasted resources, clogged courtrooms and a shift in public perception, let’s end the war on weed

Andrew Hetherington/Redux

Share

Sometime this year, if it hasn’t happened already, the millionth Canadian will be arrested for marijuana possession, Dana Larsen estimates. The indefatigable B.C.-based activist for pot legalization is thinking of marking the occasion with a special ceremony. True, it will be impossible to know exactly who the millionth person is, but with the Conservative government’s amped-up war on drugs, it won’t be hard to find a nominee. As Larsen notes, the war on drugs in Canada is mostly a war on marijuana, “and most of that is a war on marijuana users.”

The numbers bear him out. Since the Tories came to power in 2006, and slammed the door on the previous Liberal government’s muddled plans to reduce or decriminalize marijuana penalties, arrests for pot possession have jumped 41 per cent. In those six years, police reported more than 405,000 marijuana-related arrests, roughly equivalent to the populations of Regina and Saskatoon combined.

In the statistic-driven world of policing, pot users are the low-hanging fruit, says Larsen, director of Sensible BC, a non-profit group organizing to put marijuana decriminalization on a provincial referendum ballot in 2014. “We’re seeing crime drop across Canada. [Police] feel they’ve got nothing better to do. You can throw a rock and find a marijuana user,” he says over coffee in his Burnaby home. “It’s very easy to do.”

But is it the right thing to do? Most certainly that’s the view of the federal government, which has been unshakable in its belief that pot users are criminals, and that such criminals need arresting if Canada is to be a safer place. The message hasn’t changed though Canada’s crime rate has plummeted to its lowest level in 40 years. “It depends on which type of crime you’re talking about,” Justice Minister Rob Nicholson said in an interview with the Globe and Mail, a typical defence of the Conservative’s omnibus crime bill, which includes new mandatory minimum sentences for some drug crimes. “Among other things, child sexual offences, those crimes are going up. Drug crimes are going up, and so, again, much of what the Safe Streets and Communities Act was focused on was child sexual offences and drug crimes.”

The minister is correct if one takes a cursory look at the statistics. Two of the largest one-year increases in police-reported crimes in 2011 were a 40 per cent jump in child pornography cases (3,100 incidents), and a seven per cent hike (to 61,406 arrests) for pot possession. Taken together, all marijuana offences—possession, growing and trafficking—accounted for a record 78,000 arrests in 2011, or 69 per cent of all drug offences. Simple pot possession represented 54 per cent of every drug crime that police managed to uncover. This is more phony war than calamity, waged by a government determined to save us from a cannabis crisis of its own making. To have the minister imply a moral equivalency between child sexual abuse and carrying a couple of joints in your jeans underscores the emotionalism clouding the issue: reason enough to look at why marijuana is illegal in the first place.

The Conservative hard line is increasingly out of step with its citizenry, and with the shifting mood in the United States, where two states—Colorado and Washington—have already legalized recreational use, where others have reduced penalties to a misdemeanour ticket and where many, like California, have such lax rules on medical marijuana that one is reminded of the “medicinal alcohol” that drugstores peddled with a wink during a previous failed experiment with prohibition.

In late May, the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition added its voice to the debate with a sweeping report, “Getting to Tomorrow,” calling for the decriminalization of all currently illegal drugs, the regulation and taxation of cannabis and the expansion of treatment and harm-reduction programs. The coalition of drug policy experts, affiliated with the Centre for Applied Research in Mental Health and Addiction at Simon Fraser University, calls the increasing emphasis on drug criminalization under the Conservatives an “overwhelming failure.” The high marijuana use by Canadian minors is just one unintended consequence of current drug laws, it concludes. “Prohibition abdicated responsibility for regulating drug markets to organized crime and abandons public health measures like age restrictions and dosing controls.”

There’s growing consensus, at least outside the Conservative cabinet room, that it’s time to take a hard look at tossing out a marijuana prohibition that dates back to 1923—a Canadian law that has succeeded in criminalizing successive generations, clogging the courts, wasting taxpayer resources and enriching gangsters, while failing to dampen demand for a plant that, by objective measures, is far more benign than alcohol or tobacco.

Why is marijuana illegal?

Well, Maclean’s must take a measure of responsibility. Back in the 1920s one of its high-profile correspondents was Emily Murphy, the Alberta magistrate, suffragette and virulent anti-drug crusader, who frequently wrote under the pen name Janey Canuck. She wrote a lurid series of articles for the magazine that were later compiled and expanded in her 1922 book, The Black Candle — you’ll find an excerpt from this book at the end of this piece. She raged against “Negro” drug dealers and Chinese opium peddlers “of fishy blood” out to control and debase the white race.

Much of her wrath was directed at narcotics and the plight of the addict, but she also waged a hyperbolic attack against the evils of smoking marijuana—then little-known and little-used recreationally, although the hemp plant had been a medicinal staple in teas and tinctures. Quoting uncritically the view of the Los Angeles police chief of the day, she reported: “Persons using this narcotic smoke the dried leaves of the plant, which has the effect of driving them completely insane. The addict loses all sense of moral responsibility. Addicts to this drug, while under its influence, are immune to pain, and could be severely injured without having any realization of their condition. While in this condition they become raving maniacs and are liable to kill or indulge in any form of violence to other persons using the most savage methods of cruelty without, as said before, any sense of moral responsibility.”

In 1923, a year after The Black Candle’s release, Canada became one of the first countries in the world to outlaw cannabis, giving it the same status as opium and other narcotics. It’s impossible to know what influence Murphy’s writing had on the decision because there was no public or parliamentary debate. As noted by a 2002 Canadian Senate committee report, “Cannabis: Our Position for a Canadian Public Policy”: “Early drug legislation was largely based on a moral panic, racist sentiment and a notorious absence of debate.”

The Senate report, like the royal commission on the nonmedical use of drugs chaired by Gerald LeDain in the early 1970s, concluded that the criminalization of cannabis had no scientific basis, but its use by adolescents should be discouraged. The LeDain reports, between 1970-73, were ahead of their time—to their detriment. Commissioners generated reams of studies on all drug use and held cross-country hearings (even recording John Lennon’s pro-pot views during an in-camera session in Montreal). LeDain recommended the repeal of cannabis prohibition, stating “the costs to a significant number of individuals, the majority of whom are young people, and to society generally, of a policy of prohibition of simple possession are not justified by the potential for harm.” Even in a counterculture era of love beads and Trudeaumania the recommendations went nowhere.

Obscurity also befell the 2002 Senate report 30 years later. The senators recommended legalization, as well as amnesty for past convictions, adding: “We are able to categorically state that, used in moderation, cannabis in itself poses very little danger to users and to society as a whole, but specific types of use represent risks to users,” especially the “tiny minority” of adolescents who are heavy users. Generally, though, the greater harm was not in cannabis use, the senators said, but in the after-effects of the criminal penalties.

Both reports vanished in a puff of smoke, while 90 years on Emily Murphy endures. She is celebrated in a statue on Parliament Hill for her leading role among the Famous Five, who fought in the courts and were ultimately successful in having women recognized as “persons” under the law. And she endures in the spirit of Canada’s marijuana laws, which continue to reflect some of her hysterical views. Blame political cowardice, the fear of being labelled “soft on crime.” As a correspondent to the British medical journal The Lancet said of the slow pace of change for drug prohibition internationally: “bad policy is still good politics.”

Putting emotions, fears and rhetoric aside, the case for legalizing personal use of cannabis hangs on addressing two key questions. What is the cost and social impact of marijuana prohibition? And what are the risks to public health, to social order and personal safety of unleashing on Canada a vice that has been prohibited for some 90 years?

The cost of prohibition

Estimates vary wildly on the cost impact of marijuana use and of enforcement. Back in 2002 the Senate report pegged the annual cost of cannabis to law enforcement and the justice system at $300 million to $500 million. The costs of enforcing criminalization, the report concluded, “are disproportionately high given the drug’s social and health consequences.”

Neil Boyd, a criminology professor at Simon Fraser University, concludes in a new study financed by Sensible BC that the annual police- and court-related costs of enforcing marijuana possession in B.C. alone is “reasonably and conservatively” estimated at $10.5 million per year. B.C. has the highest police-reported rate of cannabis offences of any province, and rising: 19,400 in 2011. Of those, almost 16,600 were for possession, leading to almost 3,800 charges, double the number in 2005. As arrests increase, Boyd estimates costs will hit $18.8 million within five years. Added to that will be the cost of jailing people under new mandatory minimum sentences included in the Safe Streets and Communities Act.

The Conservatives’ National Anti-Drug Strategy, implemented in 2007, shifted drug strategy from Health Canada to the Justice Department. Most of the $528 million budgeted for the strategy between 2012 and 2017 goes to enforcement, rather than treatment, public education or health promotion, the drug policy coalition report notes. “Activities such as RCMP drug enforcement, drug interdiction and the use of the military in international drug control efforts [further] drive up policing, military and security budgets,” it says.

Canada has always taken a softer line on prosecuting drug offences than the U.S., which has recorded 45 million arrests since president Richard Nixon declared a war on drugs in 1971. More than half of those in U.S. federal prison are there for drug offences. The Canadian drug incarceration rate is nowhere near as high. But the government’s omnibus crime bill includes a suite of harder penalties. It requires a six-month minimum sentence for those growing as few as six cannabis plants, with escalating minimums. It also doubled the maximum penalty to 14 years for trafficking pot. (In Colorado, by contrast, it’s now legal for an adult to grow six plants for personal use or to possess up to an ounce of marijuana.)

At the heart of the crime bill, in the government’s view, is public safety through criminal apprehension. The party won successive elections with that as a key election plank, and the senior ministers for crime and justice see it as an inalterable mandate. Nicholson rose in the Commons this March saying the government makes “no apology” for its tough-on-crime agenda, including its war on pot. “Since we’ve come to office, we’ve introduced 30 pieces of legislation aimed at keeping our streets and communities safe,” he said. Public Safety Minister Vic Toews, in response to the pot legalization votes in Colorado and Washington, has flatly stated: “We will not be decriminalizing or legalizing marijuana.” Back in 2010, Toews made it clear that public safety trumps concerns about increasing costs at a time of falling crime rates. “Let’s not talk about statistics,” he told a Senate committee studying the omnibus crime bill. “Let’s talk about danger,” he said. “I want people to be safe.”

But there are risks in prohibition, too. The most obvious are the gang hits and gun battles that indeed impact the safety of Canadian streets, much of it fuelled by turf battles over the illegal drug trade. Nor are criminal dealers prone to worry about contaminants in the product from dubious grow ops, or the age of their customers.

Canadian children and youth, in fact, are the heaviest users of cannabis in the developed world, according to a report released in April by UNICEF. The agency, using a World Health Organization (WHO) survey of 15,000 Canadians, found 28 per cent of Canadian children (aged 11, 13, and 15) tried marijuana in the past 12 months, the highest rate among 29 nations. Fewer than 10 per cent admitted to being frequent users. A Health Canada survey puts the average first use of pot at 15.7 years, and estimates the number of “youth” (ages 15-24) who have tried pot at a lower 22 per cent—the same rate as a survey of Ontario high school student use by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

UNICEF called child marijuana use a “significant concern” for reasons including possible impacts on physical and mental health as well as school performance. Canadian youth, it speculated, believe occasional pot use is of little risk to their health, and “less risky than regular smoking of cigarettes.” UNICEF warned, however, of significant punitive risks to pot use, including expulsion from school and arrest. It noted 4,700 Canadians between ages 12 to 17 were charged with a cannabis offence in 2006. “Legal sanctions against young people generally lead to even worse outcomes,” the report said, “not improvements in their lives.”

Nor do Canada’s sanctions curb underage use. Germany, Portugal, Belgium, Italy and the Netherlands are all countries where pot use has been decriminalized, legalized or liberalized, and all have rates of child cannabis use that range from one-third to more than one-half lower than in Canada. Why Canada’s rates are higher is a bit of a mystery. Part of it is the ready availability from dealers with no scruples about targeting youth, and the cachet of forbidden fruit—or rather, buds. Then there’s the storm of mixed messages we send young people. There’s the laissez-faire attitude of many parents who used pot themselves. Then days like the annual 4/20 celebrations every April 20, when police turn a blind eye to open pot use and sale, cloud the issue of legality. Even the federal government vilifies cannabis on one hand, while its health ministry offers a qualified endorsement of its use as a medicine.

Mason Tvert, a key strategist in Colorado’s successful legalization vote, says criminalization has created an unregulated underground market of dealers who have no compunction about selling pot to minors. “Whether you want marijuana to be legal or not is irrelevant. Clearly there is a need for something to change if our goal is to keep marijuana from young people,” he says in an interview with Maclean’s during a foray into the Lower Mainland to campaign on behalf of Sensible BC’s referendum plan.

If you want to see the value of regulating a legal product, combined with proof-of-age requirements and public education campaigns, look to the falling rates of cigarette smoking among young people in both the U.S. and Canada, Tvert says. “We didn’t have to arrest a single adult for smoking a cigarette in order to reduce teen smoking. So why arrest adults to prevent teens from using marijuana?”

UNICEF also recommended that child pot use can be reduced more effectively with the same kind of public information campaigns and other aggressive measures used to curtail tobacco use. Canadian children, it noted, have the third-lowest rate of tobacco smokers among 29 nations. Remarkably, whether you use the 28 or 22 per cent estimate, more Canadian children have at least tried pot than the number who who smoke or drink heavily. The WHO data found just four per cent of Canadian children smoke cigarettes at least once a week, and 16 per cent said they had been drunk more than twice. It’s noteworthy, too, that tobacco, alcohol and cannabis use by Canadian children have all declined significantly since the last WHO survey in 2002. Perhaps we underestimate the common sense of our young people—sometimes at their peril.

There are ample reasons to discourage children from the use of intoxicants at a time of formative social, physical and emotional development. It’s noteworthy, though, that Canada’s teens have at least chosen a safer vice in pot—apart from its illegality—than either alcohol or tobacco. As Tvert claims, backed by ample scientific data, pot is not physically addictive (though people can become psychologically dependent) and it is less toxic than either tobacco or alcohol.

An unfair law, unevenly applied

It was a bleak, wet night in March when 100 people gathered in a lecture hall at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby to hear an unlikely cast of speakers make the case for marijuana legalization, an event sponsored by Sensible BC. Among the speakers was Derek Corrigan, the city mayor, who cut his teeth as a defence lawyer. “Over the course of my career I gained an understanding of the nature of the people who were using [cannabis] and realized this was a vast cross-section of our society,” he said. They were everyday people, not criminals, he said. Most smoke with impunity in their homes and social circles, but it was young people, without that insulation of social respectability, whom he most often defended. “In criminal law we used to call it the ‘I-didn’t-respect-the-officer-enough’ offence. If you apologized enough you were unlikely to be charged,” he said. “I found that to be reprehensible.”

Among the other speakers was lawyer Randie Long, who used to have a lucrative sideline as an hourly-paid federal prosecutor dealing with marijuana charges. There is a corrupting influence to the war on drugs that hits far closer to home than the cartels, the gangs and the dealers, he said. It corrupts the police and the justice system itself. “There’s easy money available from the feds for law enforcement”—all they need are the arrests to justify it. “The prosecutors use stats. The cops use stats,” he said. “Better stats mean better money.”

It’s understandable that many believe marijuana possession is quasi-legal. In Vancouver, it all but is. It is the stated policy of Vancouver police to place a low priority on enforcing cannabis possession charges. But outside Vancouver, most B.C. municipalities are patrolled by local detachments of the federal RCMP—and there, the hunt is on. Boyd, the criminologist, has taken a hard look at the numbers. In 2010, for instance, there were only six charges recommended by Vancouver police where marijuana possession was the only offence. There is a “striking difference” in enforcement in areas patrolled by the RCMP, Boyd notes in his report. The rate of all pot possession charges laid by Vancouver police in 2010 was 30 per 100,000. In RCMP territory, it ranged from 79 per 100,000 in Richmond and 90 per 100,000 in North Vancouver to almost 300 per 100,000 in Nelson and 588 per 100,000 in Tofino.

RCMP Supt. Brian Cantera, head of drug enforcement in the province, explained the jump in pot possession charges in B.C. as “better work by policing the problem.” He wrote in an email to Boyd: “Despite the views of some, most Canadians do not want this drug around, as they recognize the dangers of it. The public does not want another substance to add to the carnage on highways and other community problems. Policing is reflective of what the public does not want.”

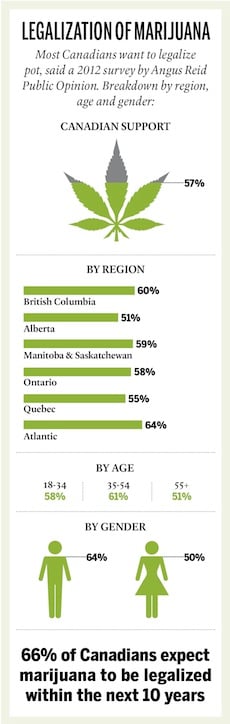

Yet many polls suggest what the public does not want is a prohibition on marijuana. Last year 68 per cent of Canadians told pollster Angus Reid that the war on drugs is a “failure.” Nationally, 57 per cent said they favour legalizing pot. In B.C., 75 per cent supported moving toward regulation and taxation of pot. The number of B.C. respondents who said possessing a marijuana cigarette should lead to a criminal record: 14 per cent.

Despite the zeal for enforcement, most pot arrests in Canada never result in convictions. In 2010, just 7,500 of possession charges for all types of drugs resulted in guilty verdicts—about 10 per cent of all 74,000 possession offences. Most possession busts never make it to trial. Of those reaching court, more than half of the charges are stayed, withdrawn or result in acquittals. This dismal batting average begs two questions. Is this a wise use of police resources and court time? And what criteria selected the unlucky 10 per cent with a guilty verdict? Aside from the probability it is predominantly young males, there are no national breakdowns by income or race. All told, pot prohibition is “ineffective and costly,” the 2002 Senate report concluded. “Users are marginalized and exposed to discrimination by police and the criminal justice system; society sees the power and wealth of organized crime enhanced as criminals benefit from prohibition; and governments see their ability to prevent at-risk use diminished.”

The human cost of prohibition

Victoria resident Myles Wilkinson was thrilled to win an all-expenses-paid trip to the Super Bowl in New Orleans this February. But when he presented himself to U.S. Customs agents at Toronto’s Pearson International Airport, he was refused entry to the U.S. because of a marijuana possession conviction—from 1981. “I had two grams of cannabis. I paid a $50 fine,” he told CBC news. He was 19. “I can’t believe that this is happening, for something that happened 32 years ago.” But it can and it does, and the fact that Wilkinson’s Super Bowl contest was sponsored by a brewery adds a painful ironic twist. Wilkinson’s predicament is sadly typical. Canadians in their late teens to mid-20s are by far the most likely to be accused of drug offences, StatsCan reports. They are also the least likely to be able to afford the several thousand dollar defence lawyers typically bill to fight a case that goes to trial.

As for the scale of pot use in Canada, look to the person on your left and the person on your right. If neither of them have violated the law by smoking pot then it must be you, and probably one of the others, too. About 40 per cent of Canadians 15 and older admitted in a 2011 Health Canada survey to have smoked pot in their lifetime. Based on the number of Canadians 15 and older, that’s 10.4 million people. Just nine per cent of survey respondents said they smoked pot in the last year, compared to 14 per cent in 2004. Male past-year cannabis users outnumber females by two to one, and young people 15 to 24 are more than three times more likely to have smoked pot in the past year compared to those 25 and older.

The same phone survey of 10,000 Canadians found that the alcohol consumption of one-quarter of Canadians puts them at risk of such chronic or acute conditions as liver disease, cancers, injuries and overdoses. If there is a crisis, it’s in that legal drug: alcohol.

Legalization and the risk to public safety

Canadians now have the luxury of looking to the social incubators of Washington state and Colorado to assess the potential risks of adding pot to the menu of legalized vices. Critics have already predicted the outcome: a massive increase in pot use, carnage on the highways, a lost generation of underperforming stoners coughing up their cancerous lungs, Hells Angels becoming the Seagram’s of weed.

As commentator David Frum described it in a column this spring on the Daily Beast website: “A world of weaker families, absent parents, and shrivelling job opportunities is a world in which more Americans will seek a cheap and easy escape from their depressing reality. Legalized marijuana, like legalized tobacco, will become a diversion for those who feel they have the least to lose.”

These are all legitimate, if often exaggerated, fears that must be addressed.

Will pot use increase? There’s little evidence internationally to suggest a surge in use, at least any more than it has as an easily obtainable illegal substance. The 2002 Senate report concluded: “We have not legalized cannabis and we have one of the highest rates [of use] in the world. Countries adopting a more liberal policy have, for the most part, rates of usage lower than ours, which stabilized after a short period of growth.”

The Netherlands, where marijuana is available in hundreds of adult-only coffee shops, is a case in point. The 2012 United Nations World Drug Report, using its own sources, pegs the level of use there at just 7.7 per cent of those aged 15 to 64. The U.S. has the seventh-highest rate of pot smokers, 14.1 per cent, while Canada ranks eighth at 12.7 per cent. Spain and Italy, which have decriminalized possession for all psychoactive drugs, are interesting contrasts. Cannabis use in Italy is 14.6 per cent, while Spain, at 10.6 per cent, is lower than the U.S. or Canada.

Is cannabis a gateway to harder drugs? Again the 2002 Senate report concluded after extensive study: “Thirty years’ experience in the Netherlands disproves this clearly, as do the liberal policies in Spain, Italy and Portugal,” the report said. “And here in Canada, despite the growing increase in cannabis users [at the time of the report], we have not had a proportionate increase in users of hard drugs.” In fact, use of cocaine, speed, hallucinogens and ecstasy are all at lower rates than in 2004, the Health Canada survey reported in 2011.

The risks of drugged driving: This is undeniably an area of concern, but one we’ve lived with for decades. Canadian law since 2008 allows police to conduct mandatory roadside assessments if drivers are suspected of drug impairment. There isn’t yet a roadside breath or blood test for drugs, but police can require a blood test under medical supervision. There were 1,900 drugged driving incidents in 2011—two per cent of all impaired driving offences in Canada.

Washington state has a standard of five nanograms per millilitre of blood of marijuana’s psychoactive chemical, THC, but there is not always a correlation between those levels and impairment. “We aren’t going to arrest somebody unless there’s impairment,” Lt. Rob Sharpe, of Washington’s State Patrol Impaired Driving Section, told the Seattle Times.

So far there has been not a spike in Washington in “green DUIs,” as they’re called. One reason for this may be that many studies have shown that people react recklessly under influence of alcohol, and cautiously when stoned. One admittedly small study at Israel’s Ben Gurion University found alcohol and THC were “equally detrimental” to driving abilities. “After THC administration, subjects drove significantly slower than in the control condition,” the study found, “while after alcohol ingestion, subjects drove significantly faster.” A World Health Organization paper on the health effects of cannabis use says an impaired driver’s risk-taking is one of the greatest dangers, “which the available evidence suggests is reduced by cannabis intoxication, by contrast with alcohol intoxication, which consistently increases risk-taking.” Most certainly criminal sanctions for any form of impaired driving are necessary, as are education campaigns.

What is the health impact of pot? Expect further studies in the states where legalization has unfettered researchers. In Canada, Gerald Thomas, an analyst with the Centre for Addictions Research of B.C., and Chris Davis, an analyst with the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, used Health Canada data to chart the health and social costs of cannabis, tobacco and alcohol. Their findings: tobacco-related health costs are over $800 per user; alcohol-related health costs were $165 per user; cannabis-related health costs were $20 per user. Enforcement costs added $153 per drinker and $328 for cannabis user. In other words, 94 per cent of the cost to society of cannabis comes from keeping it illegal.

Studies on inhaling pot smoke have yielded some surprising results. A 2006 U.S. study, the largest of its kind, found regular and even heavy marijuana use doesn’t cause lung cancer. The findings among users who had smoked as many as 22,000 joints over their lives, “were against our expectations” that there’d be a link to cancer, Donald Tashkin of the University of California at Los Angeles told the Washington Post. “What we found instead was no association at all, and even a suggestion of some protective effect.”

Another study compared lung function over 20 years between tobacco and marijuana smokers. Tobacco smokers lost lung function but pot use had the opposite effect, marginally increasing capacity, said the study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Cannabinoids in marijuana smoke “have been recognized to have potential antitumour properties,” noted a 2009 study by researchers at Brown University. A study looking at marijuana use and head and neck squamous-cell cancer found an increased risk for smokers and drinkers, while “moderate marijuana use is associated with reduced risk.” Certainly it is past time for serious and impartial study of the benefits and risks of medicinal marijuana, something that decriminalization would facilitate.

Pot as the lesser of two evils: Let’s dispense once and for all with the stereotype of the unmotivated stoner. There are also unmotivated drunks, cigarette smokers and milk drinkers. Studies have ruled out “the existence of the so-called amotivational syndrome,” the Senate report noted a decade ago. Generations of pot smokers from the Boomers onward have somehow held it together, building families and careers. Miraculously, the last three U.S. presidents managed to lift themselves beyond their admitted marijuana use to seek the highest office in the land. Once there, they forgot whence they came, and continued the war on drugs.

Consider, too, the opinion of retired Seattle police chief Norm Stamper, one of many who convinced a solid majority of voters in Washington state last November to endorse legalization. “I strongly believe—and most people agree—that our laws should punish people who do harm to others,” he writes in the foreword to the 2009 bestseller Marijuana is Safer: So Why Are We Driving People to Drink? “But by banning the use of marijuana and punishing individuals who merely possess the substance, it is difficult to see what harm we are trying to prevent. It bears repeating: from my own work and the experiences of other members of the law enforcement community, it is abundantly clear that marijuana is rarely, if ever, the cause of harmfully disruptive or violent behaviour. In fact, I would go so far as to say that marijuana use often helps to tamp down tensions where they otherwise might exist.”

As for pot’s health impact, Stamper concurs with the thesis of the book: study after study finds pot far less toxic and addictive than booze. “By prohibiting marijuana we are steering people toward a substance that far too many people already abuse, namely alcohol. Can marijuana be abused? Of course,” he says. But “it is a much safer product for social and recreational use than alcohol.”

Mason Tvert, a co-author of the Marijuana is Safer book, notes multiple studies show it is impossible to consume enough weed to overdose, yet as a teen he had to be rushed unconscious by ambulance to hospital to have his stomach pumped after drinking a near-lethal amount of alcohol. “We know alcohol kills brain cells without a doubt,” he says. “That’s what a hangover is, it’s like the funeral procession for your brain cells.”

Tvert, very much a showman in the early days of the legalization campaign in Colorado, hammered relentlessly on the “benign” nature of pot, compared to alcohol. His organization sponsored a billboard featuring a bikini-clad beauty, mimicking the usual approach to peddling beer. In this case, though, the message was: “Marijuana: No hangovers. No violence. No carbs!”

Tvert went so far as to call anti-legalization opponent John Hickenlooper, then mayor of Denver, “a drug dealer” because he ran a successful brew pub. Now, Tvert notes with sweet irony, Hickenlooper is governor, tasked with implementing the regime for legalized weed.

The rewards of legalization

Stop the Violence B.C.—a coalition of public health officials, academics, current and former politicians—is trying to take the emotion out of the legalization debate by building science-based counter-arguments to enforcement. One of its member studies concludes B.C. would reap $500 million a year in taxation and licensing revenues from a liquor-control-board style of government regulation and sale.

While some see those numbers as unduly optimistic, both Washington and Colorado are looking at lower enforcement costs and a revenue bonanza from taxation and regulation. An impact analysis for Colorado, with a population slightly larger than British Columbia, predicts a $12-million saving in enforcement costs in the first year, rising to $40 million “as courts and prisons adapt to fewer and fewer violators.” It predicts combined savings and new revenue of $60 million, “with a potential for this number to double after 2017.”

In the U.S., so far, the Obama administration has shown no inclination to use federal drug laws to trump the state initiatives. Dana Larsen is banking on a similar response from Ottawa, should Sensible BC manage to get quasi-legalization passed in a September 2014 referendum. The bar is set high. They need to gather, over a 90-day span this fall, signatures from 10 per cent of the registered voters in every one of B.C.’s 85 electoral districts to force a referendum—just as voters rallied to kill the Harmonized Sales Tax, against the wishes of the federal government. The vote, should it go ahead, would seek to amend the Police Act, instructing departments not to enforce cannabis possession. It would be the first step, says Larsen, to a national repeal of prohibition.

Would the federal government go to war with a province to protect a 90-year-old law built on myths, fears and hysteria; a law that crushed the ambitions of countless thousands of young people; a law that millions violate when it suits their purpose? Likely, but it would be one hell of a fight. After the legalization vote was decided in Washington last November, the Seattle Police Department posted a humourous online guide to pot use, entitled Marijwhatnow? Yes, it said, those over 21 can carry an ounce of pot. No, you can’t smoke it in public. Will Seattle police help federal investigations of marijuana use in the state? Not a chance. There was, between the lines, a palpable relief that they no longer had to play bad cops to a bad law. Marijwhatnow? ended with a clip from Lord of the Rings. Gandalf and Bilbo are smoking a pipe. “Gandalf, my friend,” says Bilbo, “this will be a night to remember.”

Perhaps one day Canadians will be as lucky.