Why the b-word—bankruptcy—popped up in the Newfoundland election campaign

Economist Wade Locke weighs in on the spectre of insolvency after Progressive Conservative Leader Ches Crosbie began using the dreaded word

Crosbie and PC candidate Kristina Ennis campaign in St. John’s West earlier this month. (Sarah Smellie/CP)

Share

Nearly 11 months ago, then-premier Dwight Ball of Newfoundland and Labrador wrote a letter to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau explaining that his province’s debt-to-GDP ratio, already the worst in the country, was widening further, and the province’s financial crisis needed urgent attention. It couldn’t secure any short- or long-term borrowing to fund basic services like its health-care system. The note ended with what sounded like a plea, warning that “our province has run out of time.”

Ball has since stepped down, leaving his Liberal successor, Andrew Furey, to run for re-election against his main rival, Progressive Conservative leader Ches Crosbie, who hasn’t been shy to use what has typically been a taboo word among politicians debating the state of the province’s finances: “bankruptcy.” It is widely assumed, if not certain, that the federal government would backstop any province to forestall insolvency. To Crosbie, it’s time to have that conversation in plainest terms. “When you’re negotiating with Ottawa,” he has said, “you have to know what your ultimate points of leverage are.”

Newfoundland and Labrador will start to go the polls on Saturday (a spike in COVID-19 cases has delayed Election Day in some jurisdictions). To get a better grasp of its fiscal crisis, the likelihood it might go bankrupt and what would happen if it did, Maclean’s spoke with Memorial University economist Wade Locke.

Q: What do you think about Ches Crosbie using the word “bankruptcy”?

A: Our last premier wrote to the Prime Minister’s Office to indicate he was having difficulty borrowing money to meet payroll. This was before the full impacts of COVID were felt, and before the full impacts of the fall in oil prices were felt.

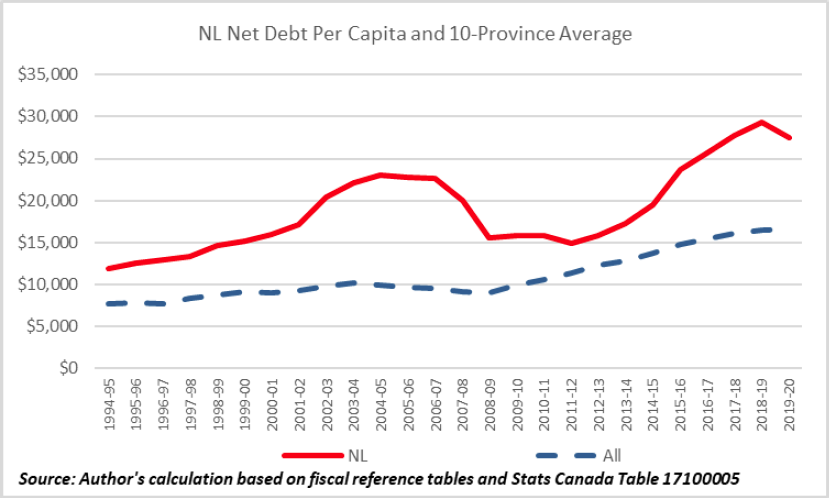

Bankruptcy means you cannot meet your financial obligations. We have a lot of financial obligations independent of what’s owed to bond holders. There are unfunded pension liabilities, post-retirement health and life insurance benefits. We’ve run a deficit every year since about 2013. We have accumulated about $16.4 billion in net debt.

There are huge adjustments needed that will result in significant decrease in people’s standard of living. We need to have substantial changes in expenditure—though it’s not clear where that should be—and there’s limited ability to raise revenue. And things don’t get easier without oil revenue. A significant portion of our labour force works in Alberta, and as Albertans are affected, so are Newfoundlanders. All those negatives are made worse by the fact that the full impact of Muskrat Falls is not yet felt.

It’s hard to say that bankruptcy is the option, but it is true we need to think through how we adjust our revenue and expenditures realistically.

Q: What would be the impact of bankruptcy, if that is an option?

A: It will have implications for Newfoundland. It will have implications for every province in the country. And it will have implications for Canada.

Newfoundland owes a substantial amount in terms of bonds, in the range of $16.4 billion with a population of just over 500,000. The ability to borrow in the bond market—for Ontario or Quebec or anywhere else—is tied to the implicit assumption that the federal government backs the bonds and won’t let the provinces go bankrupt. So the risk to bondholders is lower and therefore the rate you can borrow at is lower.

But if the implicit assumption that the federal government stands behind these bonds isn’t true, because Newfoundland goes bankrupt, then you’ll find it’s more difficult and more costly for other provinces to borrow funds. As a consequence, the absolute cost imposed upon other provinces, indirectly, would be huge compared to the cost of fixing Newfoundland’s fiscal situation.

Q: With the upcoming election are Newfoundland and Labrador’s political leaders coming to grasp the increased gravity of the situation?

A: I don’t think so. The politics of trying to get elected means the platforms aren’t consistent with the fiscal situation that we find ourselves in. What they’re doing now is designed to appease the concerns and anxiety people have going forward. No politician wants to campaign on the basis of cutting anything or raising taxes.

It seems politicians believe, rightly or wrongly, that with their policies they can grow the economy, and by growing the economy, they can make this fiscal situation a lot less severe without cutting expenditures. Based upon public reactions, it appears that people feel they aren’t being given the honest truth about the fiscal situation.

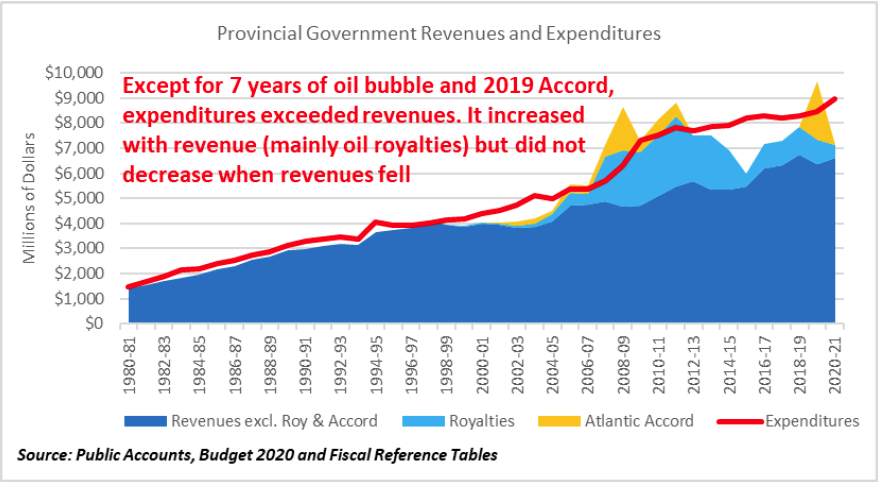

We have the highest expenditure per capita in the country. We also have the highest per capita revenue. Our expenditures went up when oil [revenue] went up, but they didn’t go down when the revenue from oil went down. That’s unfortunate but it’s the situation.

Q: Does the public have a strong grasp of what’s happening?

A: There is the public perception that things are a problem. You see a lot more letters in the paper, and more people being interviewed on TV expressing those concerns. You see people who are clearly politically partisan complaining about the lack of a plan revealed before the election. Something has to be done, but we aren’t sure what to do.

There’s going to be lots of discussion and not a lot of it will be positive when you put forward proposals. If we’re talking about closing a hospital, and that hospital is in your community, that’s something you won’t react to very well.

Q: In a recent presentation, you highlighted that Newfoundland and Labrador would need an annual surplus of $639 million, the entirety of which put towards paying off the debt, and it would take 50 years to pay off the province’s net debt. All the while, the population is shrinking and health-care costs are rising.

A: That’s correct. We have a significant problem and it’s going to take a lot to come to grips with it. I think about this a lot. We are going to have to reduce expenditure, which means reducing people. There’s no way around that. We’re going to have to raise revenue. And we’re going to have to get help from the federal government; we can’t do this on our own. If people don’t understand that, they are deluding themselves.

Q: Are people feeling the effects of the province’s financial problems in their day-to-day lives?

A: Expenditures are still going up, so you’re not feeling it now. There’s a lot more discussion about these issues on the radio, on the TV, in the paper. Whether or not actual services are getting cut, you’re starting to see that possibility.

This is all on top of COVID, so the tourism sector is screwed up now because people can’t travel. We have anxiety around outbreaks, so you can’t socialize or go out and buy things like you used to.

Q: What concrete steps would you like to see in the immediate future?

A: I would like to see a well-thought analysis of where we’re at, where we want to go as a province and a road map of how to get there. And that includes what to cut, when to cut it, how to cut it and how to grow the economy in this environment.

The other problem we’ve got is not only do we have the highest expenditures for things like health, but we also have the lowest outcomes. We have a lower life expectancy than you. That’s true for education, too. So we not only need to focus on the level of expenditure we can afford, but also how best to incorporate that expenditure. While people will talk about cuts, you need it in the right way for the right reason. It takes a lot of thought and analysis to do this correctly.

Q: I feel like this is an issue that Newfoundland’s been talking about for a while.

A: It’s easy to kick the can down the road. When you have an unpleasant situation, who wants to talk about it? Unless it’s pressing today, you say things will get better in the future. This is not likely to go away.

We’re trying to help people understand. We’ve provided advice to ministers: if you don’t do something, you’ll end up in a situation you won’t like. And that’s where we’re at now—a situation you won’t like.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.