Yachts versus rowers: In Vancouver this is class warfare

Another piece of the city’s soul is at stake, say rowers, in a proposal to expand the Royal Vancouver Yacht Club

Members of the Vancouver Rowing Club practising in Coal Harbour in 2009 (Bayne Stanley/CP)

Share

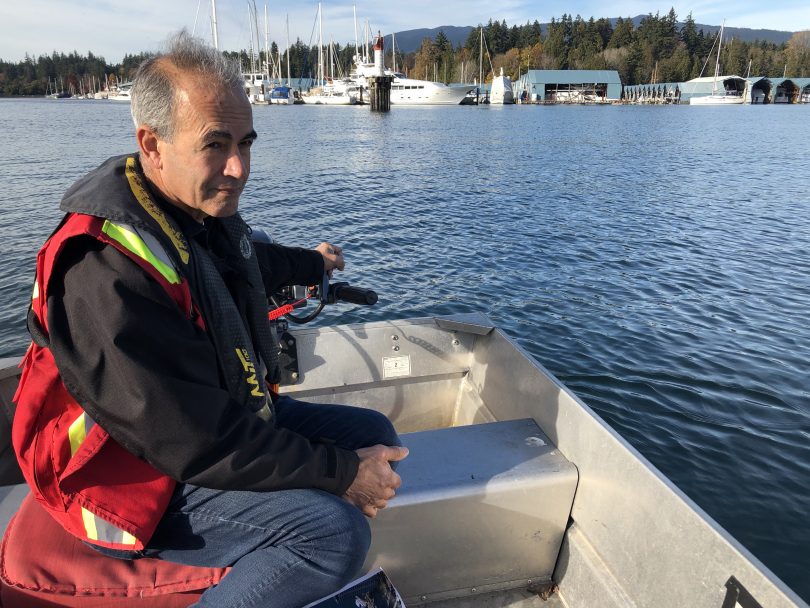

“Looking good, Bernie!” hollered Dimas Craveiro, watching brightly-dressed rowers glide past from his safety boat in the middle of the downtown Vancouver harbour on a crisp fall day. His hand on the motor, he frowned at a marina full of luxury vessels, some of them covered in tarps for the winter. The waves were quiet, but this is the site of what one former Olympic medalist says is a battle between “the big boats and the little boats.” And Craveiro is on the front lines.

It’s like a community daycare boarded up so developers can build a luxury condominium. Or a rich couple demanding the kids next door shove over a basketball hoop to make room for their giant SUV. It’s a battle between David and Goliath; a metaphor for income inequality; a new parking lot to be lamented, à la Joni Mitchell.

At least, that’s how the Vancouver Rowing Club, est. 1886, sees its feud with the Royal Vancouver Yacht Club, est. 1903, which is proposing an expansion of their marina in Coal Harbour, a busy stretch of water next to the city centre. Rowers say a bigger yacht zone will cripple their operation, making it too dangerous for a diverse population of athletes to enjoy a rare urban waterway accessible to those who arrive on foot, bikes or bus.

RELATED: Vancouver’s koi have looked into the face of death. It has beady eyes

The Royal Vancouver Yacht Club has a different point of view. Significant work has gone into developing a plan they say will leave plenty of room for everyone to enjoy the water. They are jumping through bureaucratic hoops specifically designed to ensure a fair outcome. Besides, they say, the rowing club has a marina too, where some of its members’ larger boats are parked. They aren’t so different.

Neighbours can perhaps be forgiven for developing bad blood after sharing a driveway for 116 years. But the notice that came last Wednesday was received like a passive-aggressive note on the windshield.

The yacht club was informing its neighbours that the federal Vancouver Fraser Port Authority was moving ahead with an assessment of the project design, which the club finalized in 2012 and formally submitted at the end of 2018. The design of the channel itself, and its width, would not be up for debate.

This is just the start of the review process, said Danielle Jang, a spokesperson for the port authority. Stakeholders, Indigenous groups and the public are yet to be consulted. But she confirmed that if the yacht club’s proposed boundary had been incompatible with the channel design, which has been in place since 2017, the project would not have advanced to the review stage. This makes the rowing club worry that a narrower waterway is a foregone conclusion.

“It’ll just kill us,” said Craveiro, an architect who volunteers at the club, gesturing from the open water towards areas where he said an expansion would create new blind spots in traffic.

The parking space for 47 new boats would narrow, by roughly a quarter, the skinniest part of a channel where rowing shells already compete with heavy traffic from yachts, dinner cruises and passenger boats, especially during summer. The rowers, backed by their federal and provincial sporting bodies, say heightened safety issues will make it near-impossible to train new athletes, including the 40 or so teenagers in a junior program. To learn, or to train, you need to gauge yourself against the boat next to you. Craveiro believes the expansion will make it unsafe to row side-by-side; there’ll only be room for single file.

On the water, though things have stayed largely civil, Craveiro said he has perceived a recent increase in aggressive behaviour. About two weeks ago, he said he saw a sail boat come out of the yacht club marina and steer straight towards two single rowers (one of them Bernie) as if they weren’t there. He yelled at them from the safety boat to split apart and they steered hard out of the way, with the boat narrowly missing them as it sped in between. A woman on the sailboat apologized, Craveiro said, but he sees this as part of a trend. “You get the odd person who wants to sort of put their stamp on it. ‘Hey, this is my water. Get the hell out of the way.

“I personally know a number of members at Royal Van and they are all careful and responsible, but when one of its members threads a needle between two small rowing shells in broad daylight—with plenty of time and room to maneuver—it is that image that is remembered by our rowers.”

Meanwhile, the two institutions are talking past each other, ships in the night. The rowing club says it proposed a compromise, but the yacht club ignored it. The yacht club says it offered to improve safety with flashing lights and signs, but the rowing club ignored it. Each finds the other entirely unreasonable.

RELATED: One rower, four months and a 5,000 km voyage: ‘It’s like Everest’

Ron Jupp, a retiree who heads a committee in charge of the new marina design, said the Royal Vancouver Yacht Club has no dispute with the sport of rowing. It’s not personal. “We’ve put a lot of work into designing that channel and proposed it to the port. The port has taken that information, and they’re the ones that decide on the channel, we don’t. There’s lots of room for rowing, as far as we can see,” he said mildly. “Will it be different than what they’re used to? Yeah, a little bit. But is it going to kill the sport? No, I don’t think so.”

Feeling like scrappy underdogs with the odds stacked against them, the rowing club has over the past year made efforts to raise public awareness of their plight. They successfully lobbied Vancouver city council to pass a unanimous motion Sept. 11 that affirmed “support for the Vancouver Rowing Club and the history and future of rowing in Vancouver” and promised to advocate for them in light of the expansion proposal.

The rowers came up with a campaign video featuring 1956 Olympic gold medalist Don Arnold, who framed this as a battle of “the big boats versus the little boats,” and 1992 Olympic gold medalist Derek Porter, who lamented “the breaking point” for the rowing club’s future. They set up an online petition and campaign, too, with a website, “SaveStanleyParkWaters.com,” that claims the yacht club’s motivations are purely financial. “They would rather appropriate public space to raise funds than pass along the true cost of moorage to yacht owners!” it says, claiming that the new slips would sell for $150,000 a pop.

That’s not quite the truth, either. According to Jupp, members using the new slips will pay lump sums covering six or 10 years of rent up-front to help pay for the expansion. Although he said prices vary, some could cost $100,000 up-front for a decade of rental. The payments won’t cover the full $12 million cost of the project, which would also rebuild existing infrastructure to a higher environmental standard.

RELATED: ‘Dirty money’ is destroying Vancouver’s civic fabric—and causing lasting damage

Royal Van put out its own video this week. It features a soothing female voice that explains the club’s history against a background of elevator music. The narrator does not mention the tussle over the expansion but says placidly that yacht enthusiasts have enjoyed co-operation with their neighbours, including the rowing club, for many decades.

Neither group believes the other is operating in good faith. Each believes itself to hold the moral high ground. Each is also on the side of its fee-paying members.

The review process allows for a town hall meeting, where an honest dialogue could theoretically take place. But none has been scheduled, and nobody is optimistic—least of all the port authority. It required the yacht club to hire facilitators because the event will be “high profile” and attract “vocal special interest groups,” according to Wednesday’s notice. Craveiro seemed pretty sure to whom they were referring.

It might be a stretch to characterize the fight between two harbourside private clubs in downtown Vancouver as a metaphor for a broader one between elites and the 99 per cent. But one side does represent the interests of a wealthier demographic than the other. It’s a fact the rowing club is at pains to emphasize in its attempts to swing public opinion and put pressure on the port.

Is “the big boats versus the little boats” a uniquely Vancouver example of class warfare? Craveiro didn’t want to say so out loud. It’s more about public access to the water than about money, he said, although “some people might want to go there.”

But a while later, gazing out at the marinas that pack the edges of this harbour next to Stanley Park, Craveiro showed more of his cards. “It’s really important to keep it accessible to as many people as possible, rather than to a few,” he said. “And I think that’s an argument that sort of plays across the board in Vancouver as well, and a lot of other cities, where the few are doing okay and the many seem to be shut out because of economics.”

CORRECTION, Nov. 20, 2019: The original version of this post said the Vancouver Park Board supported the Royal Vancouver Yacht Club’s proposal; while the park board had supported an earlier project to replace the club’s boat shelters, it has not taken a position on the current proposal to expand the yacht club’s water lot