Grande Prairie is the most dangerous city in Canada

Crime in Canada rose for the first time in 12 years in 2015, led by Western cities

RCMP in Grande Prairie, Alberta. (William Vavrek)

Share

Lorne Wald filled his travel mug with convenience-store coffee and warily gazed out at the youngster in baseball cap and black-and-white jacket pacing next to Wald’s grey Dodge truck. Three seconds after the 46-year-old inspector turned away to pay, the guy lunged forward and climbed into the truck. Wald ran out; the cashier, too familiar with robbery and threats at Grande Prairie, Alta. stores, locked the Wink’s front door.

Wald yanked the would-be thief from the driver’s seat; his hat went flying as the truck owner smacked him, put him into a headlock. The kid, claiming “I was just looking,” wriggled free. Their brief staring contest ended when a red car rolled by to pick up his accomplice, and the driver gave Wald a bright-orange blast of bear spray.

It was 7:38 a.m. All he’d wanted was his daily blast of caffeine.

RELATED: Canada’s most dangerous cities 2016: How safe is your city?

“Burns like a bugger,” Wald recalls of last summer’s attack. “Getting sprayed with bear spray in the morning, going for a cup of coffee—you never would have expected that before.”

But crime has become an increasingly round-the-clock phenomenon in Grande Prairie, an Alberta oil-and-gas hub 450 kilometres northwest of Edmonton. Nighttime armed robberies. Early-evening break-ins. Three of last year’s shooting deaths in the city of more than 60,000 people occurred around 5 p.m.

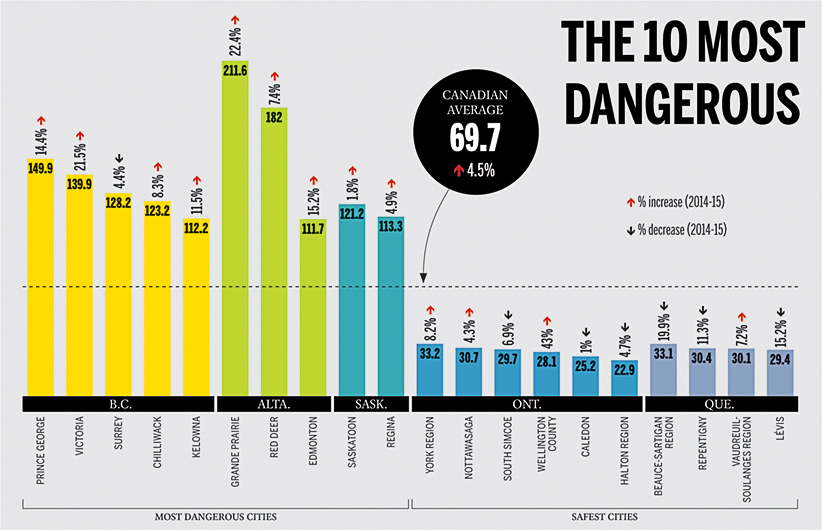

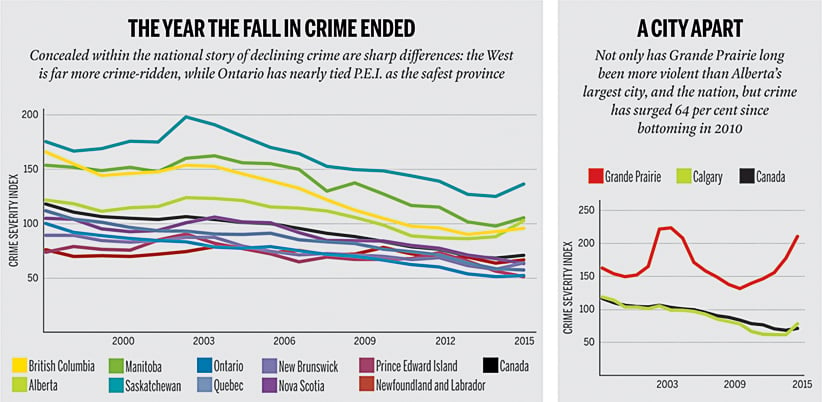

Nationally, crime rose in 2015 for the first time in 12 years, largely driven by spikes in the West likely triggered by the economic downturn and the explosive popularity of drugs like fentanyl and methamphetamines. In Alberta, the year’s 18 per cent increase on Statistics Canada’s Crime Severity Index erased five years of safety gains. But in Grande Prairie, the bust only gave added lift to a steadily worsening situation of violent acts and property pilfering.

For the second straight year, Grande Prairie was the worst among Canada’s 100 largest cities and police districts, according to a Maclean’s analysis of Statistics Canada’s collection of police-reported figures. Serenely nicknamed the Swan City, and capital of the Alberta-B.C. Peace region, the city was Canada’s worst in both non-violent crime and violent crime in 2015, which taxed an understaffed local RCMP force and eroded citizen confidence that Grande Prairie was safe.

Grande Prairie scored triple the Canadian average on the StatsCan measure, which weighs reported crimes by their seriousness, giving more heft to the worst offenses, such as murders, robberies and serious assaults, based on the length of the sentences served.

Looking at the crimes where Grande Prairie leads the nation points to how wide-ranging the problem became in 2015: No. 1 in total drug violations, firearms use, impaired driving, fraud and motor-vehicle theft. Cars, trucks or off-road recreation vehicles were vanishing at a rate seven times the Canadian average, and more than double the per-capita frequency in Canada’s third-worst city for vehicle theft, Surrey, B.C.

For crime levels to rise in a resource town’s boom and then keep rising as it busts would suggest, at least on the surface, that Grande Prairie’s woes defied economic trendlines—that danger was somehow recession-proof. But the oilpatch’s wave and ebb were precisely what kept crime surging, says Chris Millsap, a Grande Prairie defence lawyer.

It’s a young city, with a median age in the last census of 30.3 years, a decade below the national average, six years behind Alberta’s and even younger than Fort McMurray, the province’s northeastern growth rocket which has itself struggled with crime. It’s also affluent, with average incomes in six digits. During the oil boom young people with scads of disposable income turned to drugs—pot, cocaine and more addictive opiates and meth, Millsap says. Then energy drillers had to slash wages, hours and jobs. The region’s unemployment rate was 7.7 per cent in June, compared to 3.4 per cent in June 2014. “The double whammy there is whereas they could afford it previously, the economic slowdown left them with relatively few options as far as being able to pay for their addictions,” the lawyer says.

That’s why you saw young men doing what they’d never have imagined: holding up convenience stores with bear spray or guns to pay off their dealers. “If you have a Ford F-250 pickup, it’s a target for people who are going to steal that truck and sell it for pennies on the dollar,” Millsap says.

Grande Prairie’s civic leaders have in the past bemoaned a high ranking in Maclean’s pages for smearing the city’s reputation—it’s long been in the top 10 among communities its size or larger. During council budget talks last fall, though, the city’s RCMP detachment itself flagged an “exceptionally high crime rate” that had risen sharply, and has captured the national lead in severity. Senior officers said car thefts amounted to nearly three per day on average (more than triple the frequency of five years earlier). They noted 58 per cent of residents reported feeling safe and secure in Grande Prairie, a 20-point drop from 2013’s citizen survey. They also pointed out Grande Prairie’s officer-to-resident ratio was seriously below that of other Alberta cities, and the force has much higher case loads. They needed additional Mounties to bolster their investigations.

Grande Prairie’s leading officers at the time didn’t acknowledge exactly how badly the RCMP branch was buckling under its crime burden: it was routinely failing to catch and charge wrongdoers. Last year, its weighted clearance rate plummeted to one-quarter for all crimes and two-fifths for violent crimes, both well below the Alberta average and a 50 per cent reduction in Grande Prairie’s charge frequency at the start of the decade. “Candidly speaking, resources were an issue,” says Supt. John Ferguson, who took command of the Grande Prairie RCMP detachment last December. “It was all reactive policing. There was not an opportunity to do much proactive work.”

The mayor and councillors heeded the RCMP’s warning and invested $3.5-million extra in uniformed reinforcements. “When we hit No. 1, I think that definitely hurt Grande Prairie’s reputation and council acted upon that,” says Chris Thiessen, a councillor and chair of the community safety committee. Calgary’s politicians and police force reacted the same way when the July release of its 2015 crime data revealed a 29 per cent jump from the previous year (though overall, its crime is just above the national average). Mayor Naheed Nenshi and colleagues unanimously okayed the chief’s plan to spend extra traffic-fine revenue on 50 new officers.

For Grande Prairie, the extra money meant nine new officer positions and five support staff, including a crime analyst to help deploy patrols more effectively. Another eight officers are to be added by the end of 2018, bringing the detachment’s total complement to 116, and Ferguson believes the added resources are already yielding results. As of the end of June, he tells Maclean’s, Criminal Code offences had fallen by 18 per cent from the same period in 2015, setting a new five-year low of 5,388. While minor property crimes remain high, he adds, “we’re seeing a pretty dramatic decrease. Hopefully we can build on this and we’ll see the result when the Statistics Canada figures come out next year” (A press release the force sent out when StatsCan released the most recent crime data stated it was sixth on the 2015 Crime Severity Index, but that’s when one includes smaller towns like Yellowknife, population 19,000, and North Battleford, Sask., 14,000, which are too small to be included in Maclean’s list of the top 100 cities.)

Millsap, the criminal lawyer, suggests another reason for Grande Prairie’s crime drop-off: young people who came for good jobs are starting to leave, and they can’t afford to go out anymore to get into bar fights or drive home drunk. “When the ability to pay for drugs goes down, drug users go down,” he says, noting he has 30 per cent fewer clients than he did last year.

The local apartment vacancy rate validates the idea there could be fewer players in Grande Prairie’s crime game: 1.2 per cent in October 2014 became 10.4 per cent a year later. Whether it’s more cops or fewer robbers (or both), Grande Prairie citizens are breathing easier. “It’s not as brazen this year,” Thiessen says. “We went through a period where it was quite frightening for a lot of the population.”

Fort McMurray had gone through similar boom-town problems before, but leaders steadily fought to clean up its streets and reputation. Though its homicide rate was high last year, the Wood Buffalo district has slipped out of Canada’s top 10—in 2010 it held the No. 8 spot; now it is in 16th place. Steady declines have helped it get below the provincial average; Fort Mac’s score on the Crime Severity Index was less than half that of the country’s most crime-plagued city, Grande Prairie.

With all that her city has been through, including a minor flood last week and a wildfire that forced 88,000 residents to flee, the mayor of Wood Buffalo was gratified to see this year’s numbers. Melissa Blake credited the hard work of Fort McMurray’s RCMP officers, who she says worked closely with their colleagues in other Alberta cities, bylaw officers and sheriffs who patrol the province’s highways. “We’re just like citizens anywhere else,” she says. “We’ve got young families, and to me [the city’s past ranking in the crime index] is not reflective of what the community represents. The rates are showing a reduction in something we never anticipated as a big problem. But to see it going down is even more reassuring.”

Small wonder, then, that the Grande Prairie RCMP is modeling its crime reduction strategy after their Wood Buffalo counterparts. Last year, at Grande Prairie’s request, the Fort Mac RCMP sent its designated crime suppression team to the northwest city, where officers noticed some of the same criminal gang members they had previously seen back home. Impressed by the model, Ferguson has set up his own four-officer unit that in the last six months has helped take four habitual offenders off the streets while executing more than 50 outstanding arrest warrants.

If Grande Prairie’s bolstered blue line can help curb its gang violence and drug dealing, and some fairly recent newcomers depart, that will still leave the local addicts seeking a fix, and ready to take desperate measures to pay for it. Crime and fear might subside, but the scar of drug abuse may linger. When the city’s Kia dealership had its showroom windows shattered and two cars stolen last Halloween, owner Lionel Robins posted the security video on Facebook and offered a new snowmobile to anybody who helped catch the thieves. He didn’t expect who would come into his office hours after the Facebook missive: an inconsolably sobbing mother, worried it looked like her son rifling through dealership desks for car keys. A 20-something addict, he had lost his job and needed to pay his drug dealer. Robins decided that if it was her son (in the end, it wasn’t) he’d offer drug treatment in lieu of a motorized sled.

“We’re trying to be mad and upset and pissed off because we lost a couple cars,” Robins says. “We have hundreds of cars. And this lady’s sitting around having this nightmare with her kid.”

[widgets_on_pages id=”Crime-2016″]