The life and death of HMCS Cormorant—the legendary ship you’ve never heard of

The converted fishing trawler had some wild jobs: seizing drugs abandoned on the ocean floor and salvaging shipwrecks. As it heads to the scrap yard, trailblazing sailors recall its storied past.

HMCS Cormorant, a retired navy ship, has been listing in Bridgewater, N.S., for over a decade (Andrew Vaughan/CP)

Share

A tourist enjoying a sunny summer day in Bridgewater, N.S., might not have looked twice at the rusting hulk sinking slowly into the LaHave River, polluting the water for most of two decades on the province’s south shore. But last November, as a construction company towed the eyesore to a scrapyard, Gary Reddy felt a sense of relief.

Reddy had commanded the converted fishing trawler when it was called HMCS Cormorant, the floating home of Navy divers whose missions included seizing drugs abandoned on the ocean floor, guiding scientists to playgrounds of marine life, and even salvaging the historic bell from the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald. After budget cuts forced Cormorant’s decommissioning in 1997, the ship languished in Bridgewater, never to sail again.

READ: The Great Loop: The continental boating adventure even a pandemic can’t stop

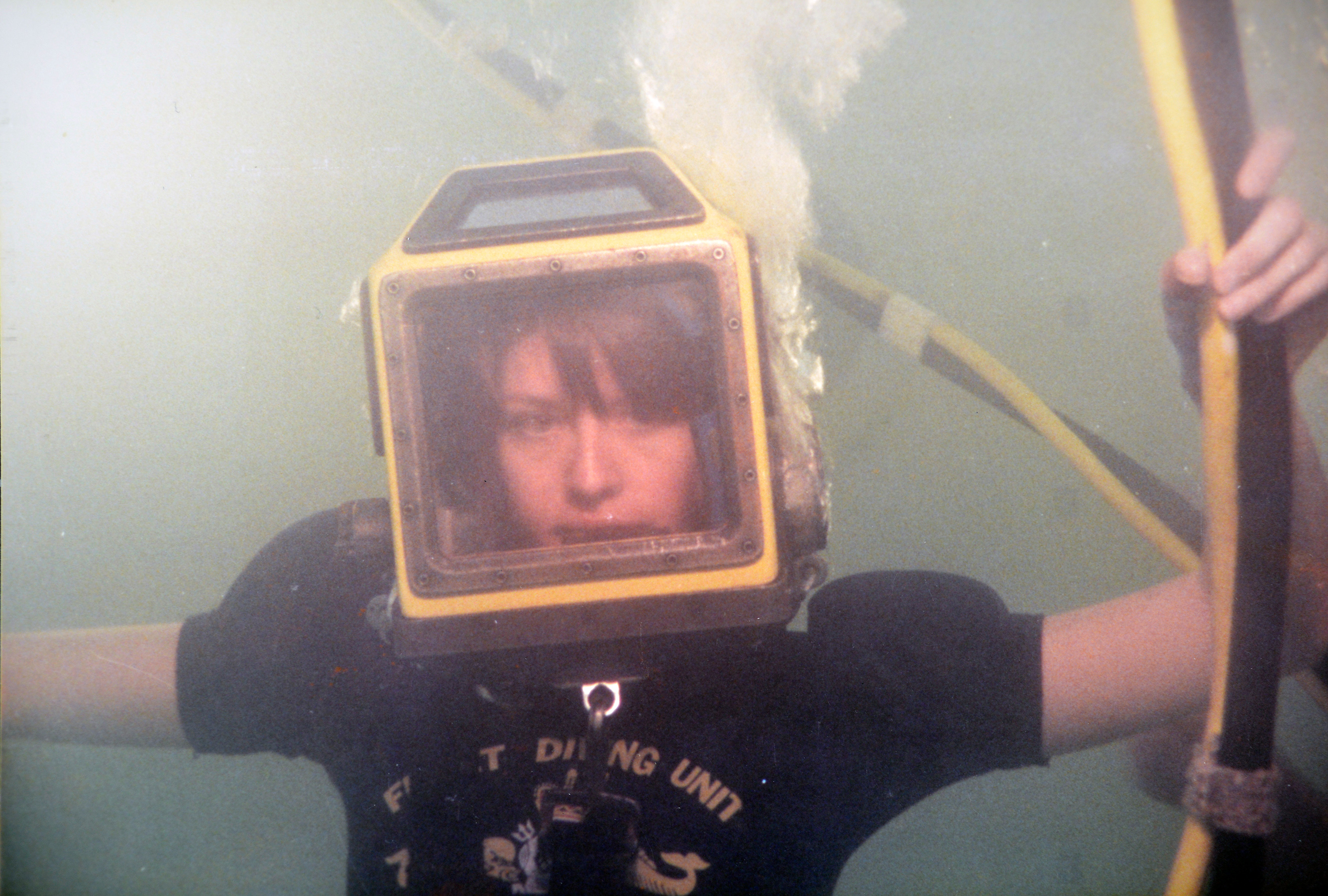

In 1978, Cormorant was new to a Navy that had plucked the 75-m vessel from an Italian fishing fleet. Back then, warships were the domain of men alone. But military brass decided to post women to one of the fleet’s smaller vessels—a ship with no large guns and a modest crew—on a trial basis. The job fell to Cormorant, an experiment that placed a cadre of trailblazing Navy women squarely in the middle of a man’s world.

Louise Fish, the first Canadian female officer at sea, and Lynn Coveney, a doctor who served on Cormorant for two years, both witnessed flagrant misogyny on the part of their shipmates. Coveney was treated as bait for bar fights at port (her crewmates lay in wait for men to flirt with her). A visiting American naval officer once rated her looks on a scale of 10 in front of the entire crew. Because the ship had women on board, men in the Navy smirkingly referred to it as “the Love Boat.”

[contextly_auto_sidebar]

Still, Coveney credits the Armed Forces for a meritocracy that rewarded competence and made her “very proud” to serve. She believes the rampant sexual harassment, while appalling, was predictable given attitudes and practices at the time that reached far above rank-and-file sailors: “They’re just guys being guys in an atmosphere where that kind of behaviour is tolerated, allowed or encouraged.”

Fish, who reached the rank of lieutenant commander and later won the Governor General’s Persons Case award for a career of military firsts, is quick to point out that a man stood behind every one of her promotions. “The fact that we were able to see that culture up close, before it changed a lot, and be accepted, even if grudgingly, was special,” she says, adding that it will take generations of women to reshape the military: “This is evolutionary. It’s not revolutionary.”

Cormorant was a bad posting for those with weak stomachs. Built as a bottom-heavy fishing trawler for Mediterranean waters, it carried two heavy submersibles on its deck—and all the tools to retrieve them. The result was a top-heavy vessel whose crew sailed at the mercy of rollicking waves. “She was a rough ride, like a corkscrew,” says Marcel Maynard, a diver and submersible technician. Fish recalled a storm off the coast of Florida. “I was so sick. I went up to the bridge because it was a mess down below, and we took a 47-degree roll,” she says. “I’m hanging on to the bridge rail, my feet are floating a bit, and I look out and see the water—but I don’t see the top of the water. I see underwater.” Dishes crashed. Cormorant needed weeks of repairs.

Over the years, crews sailed as far south as the Caribbean and as far north as the Arctic, where in 1989 divers helped explore the Breadalbane, a British ship that sank in 1853 during a search for the lost Franklin expedition. The Cormorant also recovered the black box of a CF-18 fighter jet that crashed off the coast of Vancouver Island in 1991, and later recovered cocaine off the coast of Nova Scotia after a bungled drug deal. “That was about 750 kilos,” says Maynard. “It was a big bundle.”

The Edmund Fitzgerald mission might have been Cormorant’s finest hour. A National Geographic team joined the Navy divers deep beneath Lake Superior in the summer of 1995. Every morning, they woke up to Gordon Lightfoot’s tune about the largest freighter that ever went down in the Great Lakes. They dove deep in their subs, brushing up against the sunken mammoth as they assisted a civilian diver swimming on the outside to retrieve the ship’s bell. “At 535 feet in Superior, it can be the middle of the day—bright, sunny, not a cloud—and it’s pitch-black down there,” says Phil Frazier, the pilot of the submersible that day. “Turn the lights out and you can’t see a thing.”

Often, Cormorant’s divers welcomed curious scientists aboard to help them conduct underwater research. Reddy recalls the ecstasy of a pair of scientists who studied marine life when they slowly descended to 1,000 feet below the surface: “They were like kids in a candy store.”

Occasionally, the Navy turns old vessels into artificial reefs, but most former crew members of the Cormorant weren’t upset to hear this one’s been scrapped. The ship had no future out on the water, and had become a burden to the locals. “She was tired,” says Maynard.

“There’s no life left in her,” agrees Reddy, the former captain, before offering a final Bravo Zulu—well done, in Navy parlance—for his beloved, if neglected, explorer of the ocean floor.

This article appears in print in the February 2021 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “A vessel of history.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.