A remarkable man, a remarkable legacy

Irwin Cotler on the lessons we must learn from Mandela

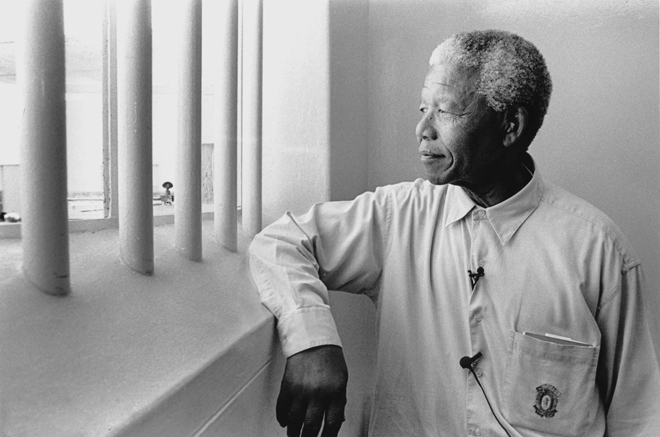

(MANDATORY CREDIT Jurgen Schadeberg/Getty Images) South Africa’s first black President Nelson Mandela revisits his prison cell on Robben Island, where he spent eighteen of his twenty-seven years in prison, 1994. (Photo by Jurgen Schadeberg/Getty Images)

Share

It is regrettably a rare occasion when members of Canada’s political parties join together in solidarity. As such, when I added my voice to those of Stephen Harper, Thomas Mulcair, and Elizabeth May as the entire House of Commons paid tribute to Nelson Mandela in the hours after his death, it was yet another manifestation of Mandela’s great capacity to unite.

My involvement in Mandela’s case and cause began when I visited South Africa in 1981 as a guest of the anti-apartheid movement. I met with, among others, faculty and student organizations, leaders of the Black Sash women’s anti-apartheid group, and members of Mandela’s legal team, including Issie Meisels, his Senior Counsel, George Bizos, and Arthur Chaskelson, then his junior counsel. Chaskelson would go on to become president of South Africa’s first constitutional court.

At the time, I was also serving as counsel to imprisoned Soviet dissident Anatoly Sharansky, and the South African Union of Students asked me to speak at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg on the topic of “If Sharansky, Why Not Mandela?” For the South African government, Sharansky was a hero in the fight against communism, whereas Mandela was a communist – and terrorist – to be fought against. In fact, Canada also considered Mandela a terrorist at the time.

I was arrested moments after I spoke, because the mere mention of Mandela’s name was a punishable offence in South Africa. While detained, I was summoned to a meeting with Pik Botha, the South African Minister of Foreign Affairs (not to be confused with Prime Minister P.W. Botha). Botha had a picture of Sharansky on his office wall, and he spent over three hours trying to convince me that the causes of Mandela and Sharansky were incompatible, and that South Africa was in fact a democratic pluralist society where black and white citizens were separate but equal. He was not impressed by my argument that both men were fighting for freedom, human rights, and human dignity, but because of the esteem in which he held Sharansky, he encouraged me to tour the country and see the true nature of apartheid for myself.

I did just that before meeting with Botha again at the end of my trip. When he asked for my impressions, I agreed that the country was indeed a plural democracy – but only for white South Africans. For black citizens, I told Botha it was worse than I had thought. South Africa was the only post-World War II country that had institutionalized racism as a matter of law, and I would oppose this racist regime from wherever I was for as long as it was necessary.

Accordingly, when I was asked by Mandela’s lawyers to be his Canadian counsel – and to advocate for him as I had been doing for Sharansky – I was pleased to accept.

Upon my return to Canada, I participated in the public launch of a major anti-apartheid initiative. Some of the Canadian organizations involved were reluctant to reference Mandela lest his supposed associations with terrorism tarnish the cause, but I believed then as now that his personal struggle was inextricably linked to the broader fight against racism and inequality.

Unexpectedly, the links between Mandela’s struggle and that of Sharansky continued as well. As counsel to both, I was asked by the South African government to help arrange a deal whereby it would release Mandela if the USSR would free Sharansky and his fellow dissident Andrei Sakharov. The Soviets declined, seeing in this a South African ploy to burnish their reputation. The South African government then sought to have me broker a new arrangement that would include the release of a Soviet general in South African custody. In the end, the general died in prison, and no agreement was reached.

In 2001, the House of Commons awarded Mandela honorary Canadian citizenship, and I was privileged to in join in the debate. As I said then, Nelson Mandela is the metaphor and message of the struggle for human rights and human dignity in our time. The three great struggles of the 20th century – for freedom, equality, and democracy – are symbolized and anchored in his personal struggle in South Africa. He represents tolerance, healing, reconciliation, and education as a precondition for a culture of peace, and his emergence after 27 years in prison – not only to dismantle an unjust regime but to build and govern a renewed and unified nation – is the ultimate expression of hope and antidote to cynicism.

Last year, I returned to South Africa at an important moment in the country’s history. It was both the 100th anniversary of Mandela’s African National Congress (ANC), and the 15th anniversary of the South African constitution, which drew for inspiration on Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In addition to reuniting with anti-apartheid activists and fellow members of Mandela’s legal team, I sought out Pik Botha and met with him again.

In the years since we last spoke, Botha had become the first South African cabinet minister to call for Mandela’s release, he served in Mandela’s government from 1994 to 1996, and he remains a member of the ANC. Indeed, Mandela’s greatest legacy may be his power to convert enemies into allies, building coalitions between diverse – even antagonistic – peoples, races, and identities, and giving expression to his vision of South Africa as a rainbow nation. He accomplished all this without rancour, anger or malice, but with a generosity of spirit and care that has inspired all in South Africa and beyond.

In the days since his passing, not only Canadian parliamentarians but people around the world have set aside their differences and united in recognition and celebration of this brilliant and beloved man. I join all those in South Africa and around the world who mourn the loss of Nelson Mandela, and who strive to learn the lessons of his remarkable life. May his memory continue to inspire us and be a blessing for us all.

Irwin Cotler is a Canadian Member of Parliament and former Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada. He served on Nelson Mandela’s international legal team.