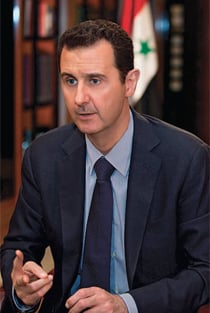

Bashar al-Assad: Not so bad after all?

Fearful of what might replace him, the West appears to be warming up to the Syrian dictator

Lebedev Artur/Itar-Tass/CP

Share

No one in Western capitals will say so out loud, but it appears the same governments that once insisted Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad must leave office are now beginning to think it might be better if he stuck around.

Today, Western governments see threats to their interests not just from Assad’s regime, which is closely allied to Iran and sponsors the Lebanese militant group Hezbollah, but also from the Muslim radicals fighting him—most notably, an al-Qaeda affiliate calling itself the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, which has become steadily more powerful. In a recent New York Times column, former American ambassador to Syria Ryan Crocker wrote that “as bad as [Assad] is, there is something worse.” He advocated “quiet engagement” with Syrian officials.

Syria’s deputy foreign minister Faisal Mekdad confirmed to the BBC last week that Western intelligence agencies have visited Damascus to discuss co-operation on “security matters.” The Wall Street Journal reported that the countries involved include Britain, Germany, France and Spain, but not the United States. A spokeswoman for the Canadian Security Intelligence Service would not say whether it has been in touch with Syrian intelligence, and a spokesman for the Department of Foreign Trade and Development says no Canadian diplomats have been to Damascus since Canada’s embassy was shuttered in March 2012.

Driving Western outreach to the Assad regime are fears about the hundreds of Western citizens who have gone to Syria to join radical Islamist rebels there. The CSIS spokeswoman told Maclean’s that Syria has become a “significant destination” for Canadians participating in extremist activities abroad. Last week, news emerged of two young Canadians who have died fighting with Islamist militias in Syria.

Officially, the policy of Western allies is that Assad should go. In practice, they have done little to make this happen. Aid to opposition groups has been mostly limited to non-lethal hardware, such as boots and night-vision goggles. America and Britain stopped delivering even that sort of thing in December, after Islamist militias seized a base and weapons depot belonging to the Western-backed Free Syrian Army.

Critics, including many in the Syrian opposition, contend that the West fuelled the growth of jihadist groups in Syria because of its half-hearted support for mainstream rebels, who were left unable to match the growing strength of jihadists funded by donors in the Gulf. Rebel activists allege that Assad’s regime, recognizing the damage extreme Islamists do to the opposition’s credibility in the eyes of the West, focuses the brunt of its force on non-Islamist opposition fighters— allowing al-Qaeda affiliates to flourish, and making Assad look like someone with whom the West shares a common enemy.

Meanwhile, earlier this month, several Syrian rebel groups launched an offensive against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Hundreds have died in the fighting. With the West unwilling to move decisively against Assad, and unsure what to do about the al-Qaeda fighters opposed to him, Syria’s non-jihadist revolutionaries are fighting an increasingly lonely war against both.