Ratko Mladic is finally captured

While the arrest of Mladic closes a chapter in Serbian history, extremist strongholds still remains

Share

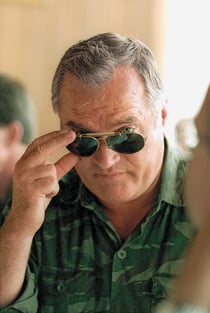

After 16 years at large, notorious war criminal suspect Ratko Mladic was arrested last week in Serbia. A former Bosnian Serb general in the 1992-1995 Bosnian war, Mladic is accused of overseeing the brutal 46-month siege of Sarajevo and orchestrating the massacre of more than 7,500 Muslim men and boys in Srebrenica—the worst mass killing of civilians on European soil since the Second World War. “This removes a heavy burden from Serbia, and closes a page of our unfortunate history,” Serbian President Boris Tadic told reporters.

On news of the capture, world leaders praised Tadic, a pro-Western moderate struggling to shed his country’s pariah image in a bid to facilitate Serbia’s integration into the EU. The May 26 arrest was vital to his efforts. The EU was unequivocal that Mladic, now 69, be caught before it would consider Serbia’s application for membership, which if successful could help boost the country’s flailing economy.

Though ethnic extremism has waned in Serbia since the president took office in 2004, stronghold pockets still persist. The Radical Party, which has branded Tadic a traitor, remains the second-largest party in the Serbian parliament. So far, thousands of ultra-nationalists have staged demonstrations and clashed with police to protest the arrest of the man they call a national hero. However, the level of disruption—and bloodshed—has been less than authorities anticipated.

With his network of government and military supporters offering him aid also diminished, Mladic was forced in recent years to rely on family to hide him. While it’s unclear how his location was pinpointed—whether through electronic surveillance of relatives or a routine raid—on the early morning of his capture, police found Mladic in the garden of his cousin’s farmhouse. He was pale, weak and alone, without bodyguards or any sign of organized protection other than two loaded pistols that he readily handed over.

Residents of the small town of Lazarevo where Mladic was caught, some 60 km north of Belgrade, say they were unaware of the fugitive’s presence. And through his son Darko, Mladic has claimed innocence: “He said that whatever was done in Srebrenica, he had nothing to do with it.” Darko Mladic and his father’s defence lawyers appealed his transfer to the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in The Hague on the grounds that two strokes have left him physically unfit to withstand a trial. That was dismissed and Mladic was extradited on Tuesday.

Mladic faces 15 counts of war crimes, including genocide and crimes against humanity, at the ICTY, where the trial of his former political boss Radovan Karadzic, caught in 2008, is under way. This arrest not only closes a dark chapter for Serbia, but also for the international community, haunted by its role in the atrocities Mladic is accused of—particularly Srebrenica, when, among other dubious decisions, a Dutch commander refused to launch air strikes to thwart the massacre. Only one ICTY fugitive remains: Goran Hadzic, ex-leader of the Croatian Serb rebels; the tribunal has indicted 161 people for war crimes during the Bosnian war, which it estimates left more than 104,000 dead.