The disappointment of Narendra Modi

Hopes that Narendra Modi would bring progress to India are fading fast as intolerance is on the rise

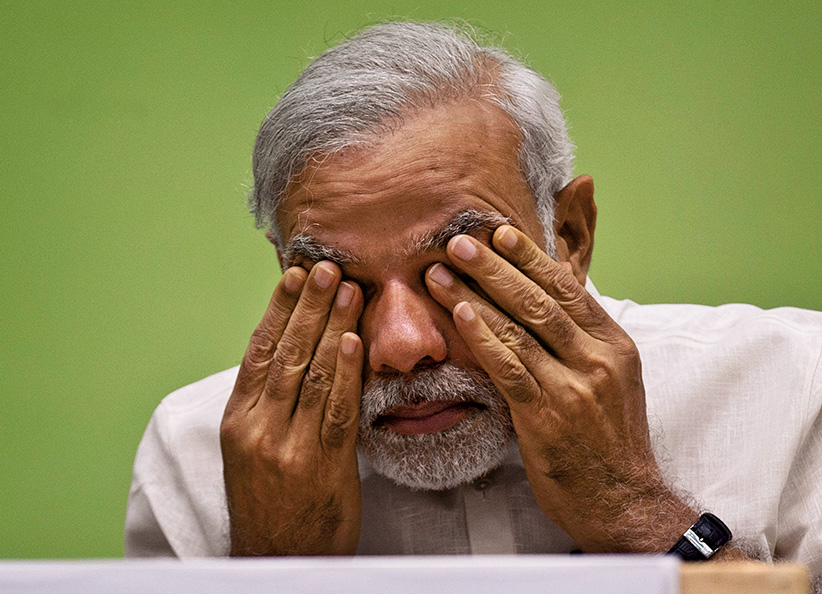

FILE- In this April 6, 2015 file photo, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi rubs his eye as he attends a conference by the environment ministry in New Delhi, India. Modi is facing a revolt within his Hindu nationalist party by senior leaders questioning his leadership style after the recent debacle in state elections. (Saurabh Das/AP)

Share

When Narendra Modi came to power in India, expectations were high. His ascent within the country’s right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) had been dramatic, earning him admirers and detractors in equal measure. Many within and outside India hoped Modi’s helming of the world’s largest democracy, brimming with youth and economic potential, would put an end to a long-running culture of socialist-style policies. Under Modi, investors expected to see a less-bureaucratic, less-regulated space where investor confidence multiplied because the hologram-using prime minister understood what a digital India needed.

This isn’t exactly how things have panned out. While India’s annual economic growth rate is healthy at 7.2 per cent, the path to progress has been slow. Modi’s supporters who believed he would fast-track progress are instead seeing the predictions of his detractors come true: an India increasingly influenced by right-wing ideology and where, alarmingly, violence against minorities and lower-caste Hindus is on the rise.

That spate of violence has led artists and scientists—more than 35 to date—to return national awards in protest of the government’s silence in the face of religious intolerance. In the past couple of months there has been a wave of murders to which Modi’s response has been underwhelming. The first was the killing of a scholar in the state of Karnataka who was known for his rationalist critique of idol worship and religion. This was followed by the public lynching of a Muslim villager in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh on the accusation that he had stored beef in his home. The conflict over beef has been festering since hardline Hindus began pressuring the state to ban the slaughter of cows, which Hindus consider sacred. BJP-led state governments have toughened up on cow slaughter, in some places imposing 10-year prison time for those who disobey. (In fact, millions of Indians, Hindus included, consume beef.) Two weeks passed before Modi made a statement about the murder.

Last week, Aamir Khan, one of Bollywood’s most-loved actors, publicly lamented that rising intolerance had made his wife (she is Hindu, he is Muslim) question whether it was safer for their family to move out of India. The comment sparked a fierce backlash; some called on Khan to actually leave the country. In response, the actor tweeted, “To all those people shouting obscenities for speaking my heart out, it saddens me to say you are only proving my point.”

There has also been caste-based violence, though that is hardly uncommon in India. Last month two children from the Dalit caste (the lowest in the caste hierarchy) died when upper-caste villagers set fire to their home. Crimes against Dalits have been on the rise in recent years—up 40 per cent between 2012 and 2014, according to data released by the National Crime Records Bureau.

Ashok Bharti, national convener of the National Confederation of Dalit Organizations, an umbrella body for minority rights groups, says that the rise can be attributed to the changing social structure in India where Dalits are no longer dependent on upper castes for their livelihoods. Many from the upper castes find that transition difficult to stomach. In addition, since the police in most parts of the country are composed of upper castes, many crimes are often not registered and go unpunished.

Modi is from the Modh-Ghanchi caste, who were originally oil pressers and were assigned “other backward castes” (OBC) status in India’s complex organized caste hierarchy. Part of his election strategy was to emphasize his roots as an OBC and a tea-seller who made his way up the caste system.

In August a coalition of Dalit rights bodies penned a letter asking the prime minister to take legal action against the Ranvir Sena, an upper-caste landlord militia accused of killing over 100 lower-caste people in the state of Bihar between 1996 and 2000. “Your lack of action on this issue gives the shocking message that Dalit and oppressed-caste lives do not matter in India.” There has been no response.

Modi, who excels at the podium, has nevertheless worked hard to cultivate the image of a progressive leader with humble roots. That effort has largely been to ward off criticism about his role in the 2002 Godhra riots in the state of Gujarat while he was chief minister (akin to a provincial premier). More than 1,000 people, mostly Muslims, died during that period. Modi’s state government was accused of not only doing nothing to quell the violence, but also of igniting it. After the Godhra riots, Modi faced a travel ban from the U.S., the U.K. and Canada.

Now in office, Modi has made every effort to visit the same countries that banned him. Since May last year he has spent close to 15 per cent of his time out of the country, speaking before packed stadiums in New York’s Madison Square Garden, Toronto’s Ricoh Coliseum and London’s Wembley Stadium. Just last month he was feted while on a two-day visit to Silicon Valley, where he connected with executives from Apple (Tim Cook) and Tesla (Elon Musk) and also with Indian-born CEOs of Google, Microsoft and Adobe.

But the thrill of his orations, full of drama and crescendo, has worn off at home. The biggest blow to Modi’s power in India came with the loss, in October, of the state of Bihar, which has a population of more than 100 million people, most settled in rural areas. “The Bihar loss has hurt Modi badly,” says Sanjay Kapoor, the editor of Hard News, a weekly political magazine. “This is the second state election that the party has lost after [Modi] helped BJP win the parliament elections.” The BJP has also lost power in New Delhi, where it won just three out of 70 seats. The party’s campaign rode heavily on the Modi factor. “Modi, with his smiling face, was peering out of every hoarding, poster, and television promo.”

Modi is now rapidly losing favour with senior leaders within his party as well as with corporate India. “Much of what he has done is optics,” says Kapoor. “I am not sure what his foreign trips have delivered. Compared to all the running around he has done to garner foreign investment, he has earned far more from all the savings the country has made from soft oil prices.”

So what did Modi promise at the outset? An end to corruption, for one (a promise much desired after years of scandals associated with the National Congress Party), better education, well-connected cities, opening up staid government-run enterprises to private companies and a friendlier investment climate. Some things have changed: In a year and a half the government has instituted reform in key areas like mining, a national skills development program is under way and a serious effort has been undertaken to expand the public’s access to financial institutions. But for investors who were looking forward to seeing the new prime minister usher in new, business-friendly policies and put an end to red-tape government culture, not enough has been done, say critics. Land acquisition reform has not taken place and infrastructure remains poor.

There is also the potential economic fallout of the country’s social troubles. Moody’s Analytics recently urged the Indian government not to remain silent in the face of increasing tensions. In a report it noted that India risks losing domestic and global credibility in the face of continuing attacks. In an article in the Financial Express, Vikram Singh Mehta, the former chairman of Shell India, argued that the country’s brand has been badly impacted by a rise in intolerance and violence directed at minority communities. More important, he writes, is Modi’s response on the issue. “His silence has surfaced disquiet about not only the ideology of the government but also its effectiveness.”

Whether already planned or in response to these warnings, the Modi government has announced more widespread reforms for foreign investment. But his detractors say that the reins of the Indian economy are still securely in the state’s hands. So too, it seems, is its cultural ideology.