The healing begins in Afghanistan

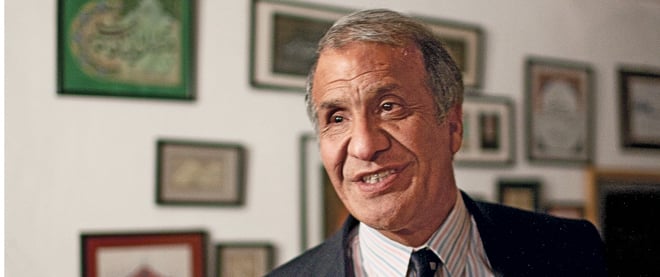

Massoud Khalili on his dreams for a new Afghanistan, and why forgiveness is so much harder than revenge

Share

Massoud Khalili woke up five days after the 9/11 attacks after drifting in and out of consciousness and near death for a week.

Khalili, son of Khalilullah Khalili, one of Afghanistan’s greatest modern poets, was a close friend of Ahmad Shah Massoud, the Afghan guerrilla commander known as the Lion of Panjshir. He was with him in northern Afghanistan on Sept. 9, 2001, when al-Qaeda agents posing as journalists detonated a bomb hidden in a video camera, killing Massoud and filling Khalili’s body with shrapnel.

The assassination was a gift from bin Laden to his host, Taliban leader Mullah Mohammed Omar, who had been fighting Massoud’s soldiers since 1996.

Khalili, then the anti-Taliban United Front’s ambassador to India, was partially blinded in the attack. Lying in his hospital bed, he opened his one good eye and saw his wife of more than 20 years. She watched him wake and recited a verse from the Quran: “From God we come, and to him we will return.”

Khalili thought he might die and wanted to do so with a clean conscience. He asked his wife to forgive him if he had ever raised his voice against her in all their years of marriage. Then he asked what happened to his friends and comrades who were in the room when the bomb went off.

Some are dead, some lived, she said. Massoud is gone.

Khalili asked about the al-Qaeda agents who tried to kill him.

They’re dead, she told him.

Today, 10 years later, Khalili strides with gusto around the garden of his summer home overlooking the Shomali Plain north of Kabul. The garden is full of fruit trees, flowers and birds. “I don’t allow my gardener to use guns here,” he says. “I’ve killed so many men. I don’t want to kill birds.”

Khalili is once again an envoy, but now of a government in Kabul rather than of a tiny and embattled rump state in the country’s north. He is Afghanistan’s ambassador to Spain. When he is home, he lives in a house built for his father by Mohammed Zahir Shah, the former king of Afghanistan. His wife’s paintings cover its walls. There are also many photos of Massoud, including what is likely the last one ever taken of him. Khalili had his camera with him when the bomb exploded. The film survived intact and when developed revealed an image of Massoud in a helicopter reading a biography of the prophets.

There is also a photo of Khalili himself with a bandolier of bullets draped across his shoulders. He sits on the ground, tilting his face toward sun with his eyes closed. It was taken in 1984, in the midst of the Afghan jihad against the Soviets. He looks blissfully happy. “The only thing we had was hope,” he says. “The only weapon we had was hope. In the mountains it was a dream to have a parliament and a president and boys and girls going to school. The worst parliament in the world is still something. Because you have it.”

Back in his summer garden, Khalili weaves among fruit trees and points to a distant hilltop. There, he says, is where Alexander the Great made his camp. “Of all the conquerors that we have had, we loved Alexander the Great because he brought us this civilization and thinkers and philosophers and painters. He conquered with this, and we believe that if he wasn’t a prophet, he was one of the saints. My father never called him Alexander, always Sir Alexander.”

He shifts his gaze east, points to snow-covered mountain peaks, and traces a line between them. “That’s the route we would take to hike into the Panjshir Valley from Pakistan,” he says, referring to the days when he and his fellow mujahedeen received weapons from CIA operatives in Pakistan and hauled them back to Panjshir to use against the Soviets. “They couldn’t move on the ground,” he says of the Russians. “But their helicopters would just fly over our houses.” Then, in 1986, the mujahedeen got Stinger surface-to-air missiles from the United States. “They no longer controlled the skies,” he says.

The Afghan mujahedeen eventually forced the Soviets from their country. But the fighting didn’t end. There was civil war, and the war against the Taliban, and then the murder of Khalili’s friend and commander, Massoud. Khalili has returned to their old redoubt in the Panjshir Valley only once since then, to see his tomb. “It was the first time I was there alone. Before it was always with him. Before there was always someone there, someone tall, who I was walking with or following.”

Now, despite a parliament in Kabul and girls in school, war persists. “But there is hope,” says Khalili. “I have an army now, police now, though not very strong. And despite corruption, we have money. And people have not raised their white flags to the Taliban. Some, yes, but not all.” Khalili cautions Afghanistan’s Western allies against a rushed exit from Afghanistan. “We should never leave the snake half-wounded,” he says. “Never fulfill a promise halfway. We would love to see them go when they have finished their job, and when we have completed our job.”

In recent months, Afghan President Hamid Karzai has intensified efforts to negotiate a peace deal with the Taliban. Khalili doesn’t think these will amount to much. “I don’t believe in moderate Taliban. You’re in Taliban or you’re not in Taliban,” he says. “They won’t talk. They fight. So what can you do? You defend. My father once wrote that war is the worst possible option. But sometimes it is an option. Because mercy to the wolf is cruelty to the lamb. Some things are so principled that you cannot make a deal on—human rights, rights of women, education. You bring peace to Afghanistan like that, with no freedom; it’s like peace in a graveyard. Stability in a graveyard is good for dead people.”

Yet Khalili doesn’t wish to prolong enmity among his fellow Afghans. Almost 100 years ago, Amanullah Khan, another Afghan king, hanged Khalili’s grandfather. Khalili once asked his father, the poet, why he never said anything bad about Khan in his poems. “He said to forgive is the most difficult thing. The easiest is to seek revenge,” says Khalili.

Khalili’s own son was with him when he woke from his coma following the al-Qaeda attack in 2001. Khalili called him to the bed. “I said, ‘Listen to me. I may be dead soon. Whatever I am about to ask of you, you tell me you’ll agree.’ ” His son initially refused, but Khalili’s wife yelled at him and he gave in.

“I said, ‘Son, I know you’re an Afghan and revenge is part of your culture. And if there is a war and you are recruited, go. Mercy to the wolf is cruelty to the lamb. But listen to me. I want to go from this life with no pain. Don’t fight on my behalf. I have already forgiven the boys who did this.’ ”