The last trip out of Afghanistan: ‘There is no way back. Taliban are outside.’

They had close ties to Canada and were being hunted by the Taliban. Trapped in a dangerous, desperate crowd, the odds were against them.

British and Canadian soldiers stand guard near a canal on Aug. 22, 2021, as Afghans wait outside the airport in Kabul, hoping to flee the country (Wakil Koshar/AFP/Getty Images)

Share

At around 10 pm on Sunday Aug. 22, Ehsanullah Ehsan received a call from the security guard at the Afghan-Canadian Community Centre (ACCC), the school he had established in Kandahar’s city centre in 2006. The Taliban, the guard told him, had come to the school looking for him, and though the guard had tried his best to be vague about Ehsan’s whereabouts, his fear ultimately got the better of him. He admitted Ehsan was in Kabul.

Upon hearing the news, Ehsan’s 24-year old daughter Balqis messaged a rapidly-expanding team of supporters scattered around the world. The group talked via WhatsApp; it had been set up to strategize the Ehsan family’s escape to Canada after the Afghan government had collapsed on Aug. 15 and the Taliban had rolled into the Afghan capital unopposed.

The family had been holed up in their apartment in Kabul’s upscale Karte Se district ever since, waiting for news of the Special Immigration Measures visa—the much-coveted SIM visa—they had applied for to Canada.

Balqis had taken on the role of communicating with the group because the strain of the family’s week in hiding had begun to take its toll on Ehsan. The Taliban had been trying to get to him for years. Death threats were the least of his worries; they’d become so common that they were routine. But there had been assassination attempts, too: one drive by shooting and another incident in which armed men had tried to run him off the road. He’d narrowly escaped both times.

Ehsan’s crime, in the eyes of the Taliban, had been to set up a school in Kandahar, with funding from Canadian donors, that had become too good at producing strong, outspoken young women who challenged the Taliban’s narrative of what women can and cannot do.

Girls who had attended the ACCC tended to move into positions of authority normally reserved for men. One, Sarina Faizy, was elected the first ever female provincial councillor in Kandahar, when she was only 16-years old. She was forced to flee Afghanistan because of Taliban death threats. Another, Maryam Sahar, was the first and only female interpreter hired by the Canadian military in Afghanistan, when she was just 15. She had fled the country, too, because of Taliban death threats.

And there were dozens more, all over Afghanistan, girls who had gone on to pursue university degrees or secured jobs with international NGOs and become breadwinners for their families.

For years, the Taliban had tried to shut the school down but for years it had been protected by the community it served. And despite suffering perennial financial crises, including the loss of Canadian government funding after Canadian forces left Kandahar in 2012, it had managed to scrape by, and was even planning to open up a branch in Kabul.

Ehsan had joined his wife and five children in the capital to set the groundwork for the new branch. But things fell apart when the Taliban arrived. Ever since, his supporters had been furiously lobbying the Canadian government to approve the SIM Ehsan had already applied for on Aug. 13.

The concern was that the longer it took to get Ehsan and his family out of the country, the more likely it was the Taliban would come looking for them. On the night of Aug. 22, time ran out.

***

A few hours before Ehsanullah received the call about the Taliban coming to his school in Kandahar, Charlotte Greenall received a frantic phone call from Omar Sahar. Omar is the 22-year old brother of Maryam Sahar, Ehsanullah’s former student. The Taliban, Omar told Greenall, were in the neighbourhood where he lived with his mother and 10-year old brother in Kabul’s Karte Parwan district. A friend and neighbour had called Omar to warn him the Taliban were banging on doors and taking away some of the male occupants.

Omar was terrified. He had already been kidnapped by the Taliban once, in 2011, and badly beaten as a warning to his sister to stop working with the Canadian military. With the group now in control of Kabul, he worried that it was only a matter of time before they found him.

Greenall, a retired Chief Warrant Officer living on Secwepmec territory near Chase, B.C., had been Sahar’s commander when she was an interpreter in Kandahar for the Civil-Military Cooperation Team in 2009. She and Sahar had grown close during their time working together on women’s rights issues and when Sahar was evacuated to Canada in 2012, they remained in contact.

Sahar had been trying to bring her family to Canada for years. When she was evacuated from Afghanistan under a program set up by Stephen Harper’s Conservatives, she was told family members were not included.

Early last July, the Trudeau Liberals announced a new program, and this one would include families, including the families of interpreters who had already been evacuated.

Sahar felt her family would be a shoe-in for the new program because she had been lobbying to bring them to Canada for so long already. But by mid-August, they still hadn’t been approved for the SIM visa, and the Taliban had now arrived in Kabul. Greenall and her husband Grant, also a military veteran, were furious. “There is no way this should have happened,” Charlotte told me. “Her family should have been in Canada already.”

Instead, Omar was on the phone to Canada asking Greenall what he should do as the Taliban slowly made their way through his building. She immediately fired off a WhatsApp message to me. Greenall and I had been trying to connect since the beginning of August to talk about her experiences with Sahar in Kandahar for a feature story about the ACCC and its impacts on Afghan women. When the Taliban took control of Kabul, we were regularly in contact over WhatsApp. “Maryam just got word that the Taliban have entered her family’s neighborhood and are taking the males,” she wrote. “We need to act fast.”

I placed a call to a contact in Kabul who quickly sent Omar instructions to move to a safe location close by. Omar took his mother and brother out through a back exit and made their way there, where they remained hidden until a friend in the building told them the Taliban had left the neighbourhood. They then quickly returned to their apartment, gathered their things, and fled.

Later that evening, I received a call from one of Omar’s family members. “They are safe at my house for now,” the person told me. “But there is Taliban everywhere. They cannot stay here for long. They need to get into the airport.”

***

On the first day the Taliban made their move on the capital, my WhatsApp feeds lit up. After two decades of covering the war in Afghanistan, I had built up a wide network of friends, colleagues and sources in the country. “No one is sleeping,” an Afghan colleague wrote to me shortly after midnight on Aug. 15, “people saying Taliban in Kabul, that they have captured entry points to Kkabul from Wardak side.”

By noon, he was sending me pictures of armed Taliban supporters openly loitering at a park in Kabul Zoo. Later, another colleague sent me a video of prisoners streaming out of Kabul’s infamous Pul e Charkhi prison. “Adnan, that is Pul e Charkhi prison,” he said on the recording, the camera panning along a line of people more than a kilometer long. “Look at all those people.”

New WhatsApp groups were forming almost by the minute, some coalescing around individual people under threat and others around national evacuation efforts like Canada’s. Many Canadians outside of government were working furiously to help rescue thousands of Afghans at risk. They included former military personnel, diplomats, aid workers and other people with a connection to Afghanistan. I was pulled into one group, created to help the Ehsan family, and another with Greenall to assist the Sahars, with the hope that by pooling resources, a way could be found to get the families evacuated.

Both those efforts reached a crisis point on Aug. 22. On that night, the focus was on Ehsanullah and his family—the Sahars were, for the moment, safe at their family member’s home. The question was just how exposed Ehsanullah was now that the Taliban knew he was in Kabul. He was relatively certain they didn’t know his exact location in the city but there were some concerns about the fact that they now controlled government offices and could track him down through various city records.

The consensus on the WhatsApp group was that the family needed to be moved, but where? Group members, including Ryan Aldred, who had helped Ehsan set up the ACCC, as well as journalists and humanitarian workers from the U.S. and Canada who admired what Ehsan had done for girls’ education, reached out to contacts in Kabul who had set up safehouses. But those had filled up quickly.

Someone proposed the five-star Serena Hotel, where high-level officials, businesspeople and contractors were taking shelter. Costs would be high: the Serena’s management, we were told, was limiting room occupancy to three people so housing the seven-member Ehsan family would mean three rooms at a total cost of US$750 per night, plus food at the hotel’s gourmet restaurants.

The hotel retained some degree of untouchability because of the high-level officials taking cover there. There were also U.K., American and Qatari convoys travelling to the airport from the hotel, which were reportedly being allowed in, as well as helicopter evacuations. A delegation of Qatari officials in the hotel was reportedly acting as mediator between elite internationals looking to reach the airport on buses and the Taliban.

The thought of these five-star evacuations as thousands of ordinary people faced life or death scenarios in the worsening chaos on the streets outside the airport was sickening. But in that moment, the group helping the Ehsans saw no other option.

By this point it was past midnight in Kabul, a little over two hours since Ehsan had received the call from the guard at the ACCC. Calls were made to find someone inside the hotel who could help book rooms and pay for them. We were told booking online was no longer an option; the hotel was only accepting cash. The possibility was floated of asking a foreign security company inside the hotel to cover the costs and reimburse them, but nobody had a connection to the company.

Then everything collapsed. At two in the morning, the contact in the Serena told the group that moving the family there would not be advisable if the Taliban were looking for Ehsan. Taliban fighters had begun to patrol the hotel’s halls, he said. The security situation inside was looking tenuous.

Deflated and desperate, the group fired off some longshot alternatives: perhaps somebody knew a wealthy benefactor to pay for a charter jet, maybe the family could be muscled onto a flight to a third country in the region where they could temporarily shelter until their Canadian visas were approved.

One of the people in the group had contacts at Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) who told him the approval was pending and would happen soon. That seemed to be the only solution. Once that happened, the Ehsan family would receive instructions from IRCC officials about what to do to reach the airport. The thought of that ordeal was frightening enough but it was a bridge that would have to be crossed once the more pressing issue of the visas was solved.

***

The chaos at Hamid Karzai International airport really boiled down to one early mistake: The first few evacuations to leave Kabul included many hundreds, perhaps thousands of people who managed to board planes without any documents or proof that they faced Taliban threats.

Their successes led to more people converging on the airport, many with only the flimsiest connections to the international presence. Stories began to spread of people gaining access to the airport with an electricity bill and a passport or with forged documents claiming they had worked for one foreign NGO or another, prompting more people to make an attempt.

By the time the international community managed some semblance of a vetting process, the damage was done: Chaos ruled, and the Taliban appeared to have no real interest in bringing it under control. They were either letting everyone make their way to the various gates manned by international forces, including Canadians, or randomly deciding they would block everyone, whether they had approved visas or not.

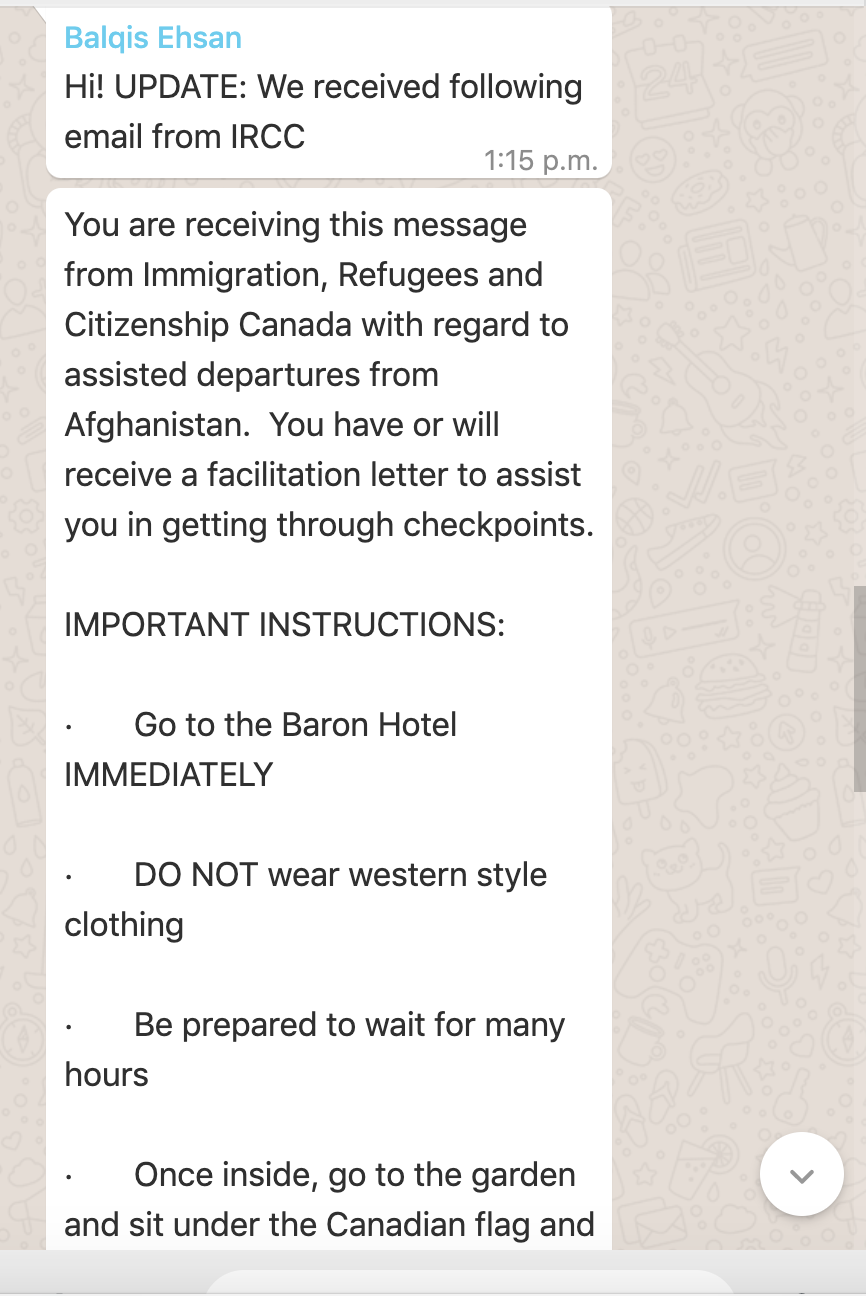

On the morning of Aug. 23, the push was on to get both the Ehsans and the Sahars approved. Every string that could be pulled was pulled, every connection, no matter how distant and tenuous, tapped. And then, at 1:15pm, we received a message from Balqis:

“Hi! UPDATE: We received following email from IRCC:

You are receiving this message from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada with regard to assisted departures from Afghanistan. You have or will receive a facilitation letter to assist you in getting through checkpoints.

IMPORTANT INSTRUCTIONS:

· Go to the Baron Hotel IMMEDIATELY”

I called Omar and asked him to check his email. He had received the message, too.

The Baron Hotel was a compound adjacent to the airport that was popular with internationals. A source in Canada had told me people who had received the IRCC emails were being collected on the hotel grounds where their documents were verified. They were then being escorted by Canadian Special Forces into the airport.

Omar Sahar, his mother and his younger brother were the first to arrive at the road leading to the hotel’s main gate late in the afternoon of Aug. 23. The scene was utter mayhem. The Taliban were preventing people from reaching the hotel, shooting in the air and beating those who tried to get past them with their rifle butts.

“They come to one side of the street and then people try to run past them on the other side,” Omar said in a WhatsApp audio recording, with the sounds of gunfire in the background. “I am with my mother so we cannot run.”

They abandoned the instructions from Canadian officials and decided to look for another way into the hotel compound, but everywhere they tried there were crowds and chaos. At one point they found themselves having to wade through putrid sewage water in a canal at the end of which was a crowd so thick that it surged and rippled. Seeing that, they gave up and went home.

Ehsan and his family arrived some time after the Sahars and somehow managed to get themselves stuck in that same mass of people Omar had decided to avoid. As night fell, they realized they were trapped. Going forward was impossible, and going back too dangerous in the dark. “We are here. It is terrible,” Balqis wrote on the WhatsApp group. “We were badly beaten by Taliban … (on) the way. There is no way back. Taliban are outside. And other soldiers are saying there are no Canadians.”

What the IRCC instructions had failed to mention was that Canadian forces did not remain outside after 5:30pm. The Ehsans were, effectively, on their own.

Frantic calls went out to officials in Ottawa. U.S. soldiers were still guarding the perimeter of the airport so calls were made to contacts in the U.S. to see if the family could be brought inside that way. Nothing was working.

Finally, someone managed to find the contact of a Canadian contractor, David Lavery, who we were told was inside the Baron Hotel. A message was sent to him on Signal; two hours later he responded: “Are they on the back gate? We will try to get them in. What’s there [SIC] name?”

All of their information was sent, including the GPS coordinates for their location, gleaned from WhatApp’s location services along with multiple descriptions of their surroundings including photographs as well as Ehsanullah’s phone number.

And then the waiting began.

It was 10pm and the crowd had calmed. People were settling in for a long, chilly night. To keep the Ehsans occupied, the group of supporters strategized their next moves. Some suggested it might be worth a try to head to the front gate of the Baron Hotel, where the Taliban were blocking the way earlier. Perhaps they were gone. But one of the group’s contacts in Canada advised against it. He had heard of people being robbed at night of their documents. The best course of action was to hang tight and see if someone from inside the hotel compound could come out and take them.

At 11pm, Lavery finally messaged. He said he would try to make an attempt at 5:30 in the morning. The Ehsans resigned themselves to a sleepless night, clinging to the hope that in a few hours, they would be rescued.

***

Omar Sahar and his family ventured back out onto Kabul’s empty streets at five in the morning on Aug. 24 hoping that the Taliban would not be blocking the way to the Baron Hotel’s main entrance at such an early hour. The morning call to prayer rang out as they approached the airport. Most of the city had remained calm throughout the Taliban takeover and Omar felt a pang of regret as the taxi cruised through its quiet, leafy neighbourhoods. It is a beautiful city, he thought to himself, and given another reality, one without war and the Taliban and foreign occupations, he could see himself building a life for himself here.

But as the taxi approached the street leading to the Baron, he could make out the crowds, and the Taliban fighters. He had hoped, being the strict Muslims they were, they might have gone for their morning prayers. Instead, the cat and mouse game was on again with a mass of Afghans trying to get past the Taliban checkpoint and the militants deploying their usual crowd control methods: shooting in the air and rifle butts to the head and body.

In a WhatsApp voice message, Omar suggested joining Ehsan and his family but I told him that was risky. The crowds there were making it too difficult to move and I didn’t want him, his mother and younger brother to get trapped as well.

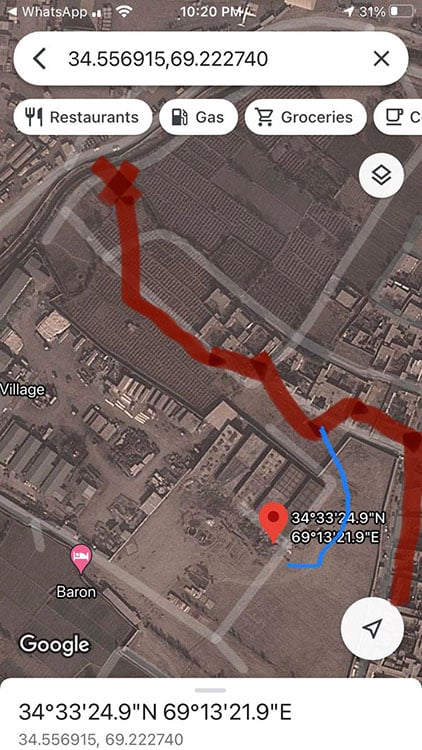

The only option I could see for him was to find a way to get past the Taliban. But then a message came in through Ehsan family’s WhatsApp group: Canadian officials were telling people to now go to the back gate of the Baron hotel. I quickly jumped onto Google Maps satellite view and dropped a pin where I thought the back gate was. I couldn’t be certain but it was the only route around to the back side of the Baron that was accessible at that time. The alternative was to send the Sahars the same way the Ehsans had gone.

I took a screenshot of the location and sent it to Omar. “Go there,” I told him.

***

While the Sahars were making their way to what I hoped was the back gate, Ehsanullah and his family were still waiting for the extraction Lavery had said he would attempt at 5:30am. It was already six and I had sent him another message. The crowds along the canal were building. Balqis was speaking in near apocalyptic terms, describing the situation as “suffocating” and a “catastrophe.”

A few Canadian soldiers had appeared briefly but had then disappeared again, shouting that they would be back. They had been too far away from the Ehsans for them to get their attention. The WhatsApp group decided that Lavery’s extraction was not going to happen and the only way to save the Ehsans was to find a way for them to get to the Baron Hotel’s back gate, as instructed by Canadian officials. They were excruciatingly close already: if they could just move forward 50 m or so they would be there. But the crowd ahead was impenetrable; and now, the crowd behind them had swelled as well. Escape was impossible.

Things started to unravel. Desperate pleas were sent to any contact the group could think of, in Canada, the U.S. and in the Kabul airport. The crowd was becoming more chaotic as people tried to plea with foreign soldiers, mostly Americans, to look at their paperwork and let them in. It had become so thick that Balqis felt as if she was suffocating. In a moment of panic, she jumped into the canal, landing in the filthy, knee-deep water. “I am in the middle of valley alone,” she wrote to the group. “I lost everyone else.”

***

Omar and his family had reached the back gate without much difficulty but the scene there was discouraging. Omar could see Canadian soldiers but getting anywhere near them meant battling through another crowd, with his mother and 10-year old brother, and then wading through filthy canal water nearly a meter deep.

Still their situation was infinitely better than what the Ehsans were facing. Omar joined the crowd and began pushing forward. It was slow going but in a little less than an hour he was within shouting distance of the soldiers, though not close enough to show them his documents. His brother and mother were waist-deep in water and Omar was becoming distraught.

“They are not listening to me,” he pleaded in a WhatsApp recording. “We are waiting in the water but they are not taking our documents.”

I told him to keep fighting for their attention and try to push even closer. After an hour he was becoming frustrated and was on the verge of giving up. I called the Greenalls in British Columbia and asked them to call Omar to encourage him to stay strong. This was his best chance at getting in, and he had already made it so far.

Shortly after, I received another voice message from Omar: “Hello,” he said, sounding relieved. “We are in now. We are with the Canadian soldiers. Thank you.”

***

Back with the Ehsans, the panic that had rippled through the WhatsApp group when Balqis was separated from her family was thankfully short-lived. After losing sight of his daughter, Ehsanullah had also taken his family into the canal, and they were reunited with Balqis there. But now they were in the water, and the crowd on the walkway was so unruly that finding a way out would be difficult.

I broke off into a private WhatsApp chat with Aldred. It wasn’t looking good, I told him, my body buzzing from a combination of lack of sleep and adrenaline. The family had somehow gotten itself trapped in a bottleneck but needed to get to the back gate of Baron Hotel. “If they can extract themselves from that situation and go around the other way, the way Omar took, I think they can get there,” I wrote.

I sent him a screenshot of a map for the route I thought they needed to take. Aldred thought it made more sense to keep the messages flowing to Lavery inside the Baron Hotel. He was right. Pushing through the crowds at this point would be futile. Lavery had said more or less the same thing the night before. Canadian officials knew where the family was and we had to just hope they would come for them.

And then suddenly, a message came through from Balqis: “We are out of the valley. Sitting inside in a place. The Canadian soldier said they will check passports here.”

***

It’s still not clear exactly how the Ehsan family was rescued. According to Balqis, Canadian soldiers suddenly appeared and pulled them inside the grounds of the Baron Hotel. No one is sure if Lavery was responsible for sending them, or if the family just happened to be in the right place at the right time, or if Haroon, Ehsanullah’s son, had tracked them down and alerted them to the family’s predicament.

As of writing, the Sahars had landed in Toronto but the Ehsans were still at a military base in Kuwait without internet access.

Their ordeal was far from over. They were now in quarantine after testing positive for COVID-19. They had received some medical attention but Ehsanullah was still in bad shape.

But at least they were out of Afghanistan. The Ehsans and Sahars were among the last people evacuated after the Liberal government decided to end the evacuation efforts on Aug. 26, shortly after a suicide bomber and at least one attacker reportedly sent by the Afghanistan branch of ISIS killed more than 170 people, including 13 U.S. soldiers, at almost the exact spot where the Ehsans were trapped only two days earlier. It’s unclear how many of the dead, if any, had been approved for the SIM visas and may have been trying to enter the airport for an evacuation flight to Canada.

One family, requesting anonymity because they are still in Kabul, told me that they had left the area after receiving a message from Canadian officials about an imminent attack. Two other families they knew who were also there with Canadian documents had also left. But others had not.

Thousands more, including Canadian passport holders, permanent residents and Afghans approved for SIM visas—as well as those under threat from the Taliban but still looking for a path to safety—remain inside the country with diminishing hopes of escape.

It’s unclear what will happen to them. Many Whatsapp and Signal groups have shifted gears from emergency airlifts to overland routes, but those remain dangerous. The Taliban keep insisting that anyone with “legal documents” will be allowed to leave on commercial flights once the Kabul airport is functioning again but no one is sure what they mean by “legal.” They have indicated that Afghan passport holders can freely come and go from Afghanistan but, with their usual ambiguity, have not indicated if passports issued by the previous government will remain “legal.”

If not, and every Afghan is forced to apply for new passports through a Taliban-run Interior Ministry, there are concerns that issuing those documents will become a form of control, like in Iran. Afghans the Taliban wish to keep in the country, for whatever reason, will be denied passports.

For the many Afghans who have been approved for SIM visas but were unable to make the escape to Canada, this is the terrifying possibility: they may never be able to leave.