The meaning of the meddling Prince Charles

Charles’s lobbying letters defend the toothfish and the badger cull. Do they also put the monarchy at risk?

Mandatory Credit: Photo by REX Shutterstock (4774725i)

Prince Charles signs the visitors book as he arrives to look around the “Mayas: revelation of an endless time” exhibition at the World Museum, celebrating a ‘Year of Mexico in the United Kingdom’ as part of his visit to Liverpool

Prince Charles and Camilla Duchess of Cornwall Visit Liverpool, Britain – 14 May 2015 (Rex Shutterstock/CP)

Share

Should an heir to the throne be allowed to voice his opinions in public, and if so, when and in what context? This is the question at the centre of the royal family’s latest legal fiasco, an expensive court battle that was lost last week at great cost to the British public. After years of legal wrangling, both the palace and the government failed in their attempts to keep hidden the private correspondence of Prince Charles with various government ministers in the years of 2004 and 2005.

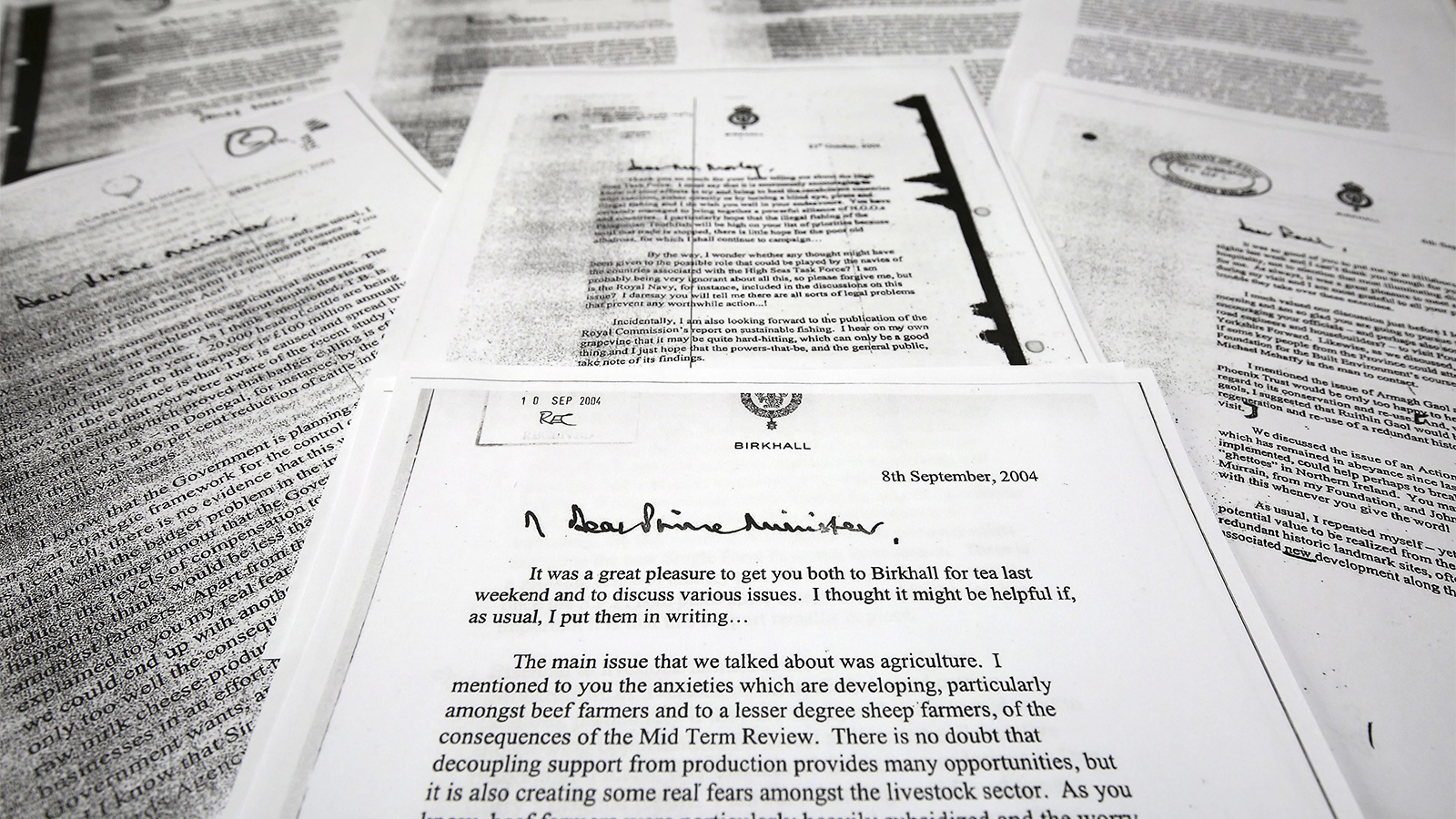

Known for decades within government circles as the “black spider memos” (a reference to the Prince’s sprawling black scrawl), the letters have been a matter of significant public scrutiny since 2010, when the Guardian made an application under the British Freedom of Information Act to have the letters made public. After many appeals, the request was finally vetoed by the government in 2012, but that decision was struck down last week by the British Supreme Court.

After all this lead-up, the big reveal was rather lacking in surprise. Reading over the 27 letters, which were sent to Tony Blair and various members of his cabinet, the Prince emerges as an engaged, thoughtful and meticulously polite lobbyist with a rather eccentric array of pet causes and political interests ranging from military spending during the Iraq war to farming legislation and animal rights. In other words, exactly what one might expect of an aging royal with a vast amount of arable land and a good deal of time on his hands.

Related: What the black spider memos reveal about Prince Charles

Among the Prince’s chief interests are farming—he is a huge proponent of Britain’s controversial badger cull and a supporter of independent dairy producers. He harshly criticized supermarkets, saying their conduct put food producers at risk. He takes an interest in architecture (basically he hates anything that could be classified as “modern”) and his love of certain animal species (barring badgers) also abounds. As he wrote to environment minister Elliot Morley in 2005, “I particularly hope that the illegal fishing of the Patagonian toothfish will be high on your list of priorities, because until that trade is stopped, there is little hope for the poor old albatross, for which I shall continue to campaign.”

But perhaps the most successful effort of the “meddling Prince” (as he once called himself) was convincing then prime minister Tony Blair to delay by several years European regulations on herbal medicines. This lobbying victory prompted critics to point out that the Prince’s views, which rest on bad science and a vaguely hippyish belief in “natural remedies,” were given special regard by Blair.

But the issue at stake here is not really Prince Charles’s personal popularity (which has always been pretty dismal compared to his mother or his eldest son), but whether he has breached his impartiality and exercised undue influence over government ministers as heir to the throne.

Once Charles ascends as monarch of the realm he will be expected to remain publicly impartial on matters of state, as his mother has very carefully managed to do in her nearly 63 years on the throne. The Queen has views that she expresses in private (she meets with the British prime minister on a weekly basis), but in public life she remains an enigma wrapped in a pastel skirt suit. It is a stance that is both a matter of decorum as well as a central pillar in the smooth functioning of a constitutional monarchy. This is why, some constitutional experts say, the court was correct to release the letters. “The future of constitutional monarchy depends on a politically neutral Prince,” Lord Pannick, a constitutional lawyer who sits in the House of Lords, said this week. “The reason why the Supreme Court judgment was correct is that the Prince is trying to have it both ways: to campaign now, but also to claim confidentiality for the letters because he says he is preparing for monarchy.”

But others who are more sympathetic to the Prince argue that he should have the right to engage in public discourse, and that furthermore, we should be grateful to have a future monarch who takes a serious interest in public policy (as opposed to, say, George V, who did little his entire reign, apart from hunt and collect stamps). Jack Straw, a Labour MP who was one of the original architects of the Freedom of Information Act, went on BBC Radio last week to defend the Prince’s right to private correspondence with government ministers. Vernon Bogdanor, a professor of government at King’s College London, told the press that, in his view, none of Charles’s letters “impinges in any way upon party politics, and therefore they in no way undermine his political neutrality.”

It seems unlikely that the letters will damage Charles or the monarchy. As Catherine Mayer, author of the Prince’s most recent biography, remarked this week, “The people who think that he oversteps the mark will be confirmed in their opinion, and the people who like what he does will like him more.”