The terrorists are winning the ‘War on Terror’

Adnan R. Khan: Eighteen years after 9/11, the world is fractured and in turmoil. That was Osama bin Laden’s plan all along.

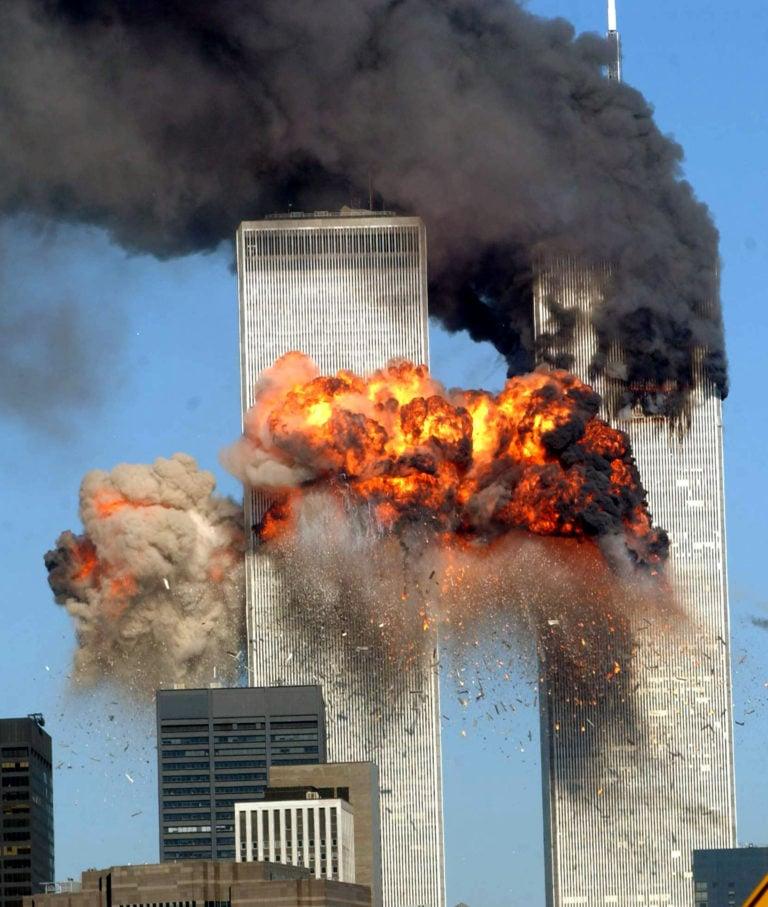

A fiery blasts rocks the south tower of the World Trade Center as the hijacked United Airlines Flight 175 from Boston crashes into the building on Sept. 11, 2001 in New York City. (Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

Share

On Jan. 27, 2017, not long after being inaugurated as America’s 45th president, Donald Trump made his first attempt at introducing a ban on foreigners entering the United States. The ban singled out seven Muslim-majority countries and decreed that its citizens were persona non grata in the U.S.

Administration officials insisted the ban had nothing to do with Islam. It just so happened, they argued, that ISIS and al-Qaeda terrorists were actively operating inside those countries and, naturally, were looking for ways to come to America to carry out attacks.

Never mind the statistics showing that new immigrants, particularly those from the seven banned Muslim countries, have never carried out any terrorist attacks in the U.S., or that rates of violent crime are lower among immigrants than American-born citizens.

The Muslim ban, as it was quickly labelled, sparked outrage among large portions of the American public. Protesters flooded into American airports, accompanied by immigration lawyers to advocate for travellers caught in the dragnet.

I was in northern Iraq at the time, covering the Iraqi army’s offensive to retake Mosul from ISIS. The ban had an especially devastating effect on Iraqis, who were included in it, particularly those who had worked with the Americans during the occupation of their country. Two months earlier, in November 2016, some of those same Iraqis, now working as translators and fixers for the hundreds of foreign journalists camped out in Iraq’s Kurdistan region, watched in horror as Trump unexpectedly won the presidential election.

READ MORE: Trump’s new order: A ‘Muslim ban in sheep’s clothing’

Their fear was twofold: first, Trump had promised during his election campaign to pull American troops out of Middle East entanglements. He claimed, dishonestly, that he had always been opposed to the war in Iraq and that keeping troops there was not in the U.S. interest (though controlling Iraq’s oil, he mused, was). From the Iraqi perspective, the 2003 American invasion and the chaos it unleashed had been devastating. By the end of 2016, Iraq had suffered through 13 years of corrupt rule, a sectarian civil war and a war against al-Qaeda that had evolved into a war against ISIS. Iraqi soldiers were fighting, and dying, on the front lines in Mosul, and those I knew were terrified that the U.S. under Trump would simply cut and run, leaving behind the festering wound it had inflicted on their country.

There were also those who feared what Iraq could become in the absence of a foreign presence. The real winner of the American invasion had been Iran, which had, over decades, nurtured contacts among Iraq’s Shia population. In the wake of the invasion, Iran’s political influence had grown exponentially, and in the aftermath of ISIS’s brutal march through Iraq and Syria, it was Iran that now, through its armed proxies, exercised ever-growing military control.

Trump’s election was the culmination of a decade and a half of American foreign policy gone horribly awry in the era of the “War on Terror.” A splintered Iraq and resurgent Iran were only two ripples in its wide-ranging effects.

That first Muslim ban has now been expanded. Asylum seekers from South and Central America have been turned away at the U.S.-Mexico border, accused, without proof, of being terrorists and gang members. Children have been separated from their parents, placed in cages and subjected to conditions rights organizations have described as “disgusting” and “inhumane.”

And Trump is promising more. “We have to be safe. Our country has to be safe. You see what’s going on in the world,” he said on Jan. 22 during a press conference at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. “So we have a very strong travel ban, and we’ll be adding a few countries to it.”

To counter Iran, he has resorted to confrontation and violence, assassinating one of its leading military figures, General Qassem Soleimani, on Jan. 3. He has put the U.S. on a war footing, claiming, inaccurately, that he has pumped US$2 trillion into buying military equipment that could be used to hit Iran. (The actual figure, say military experts, is US$420 billion. And in a war with Iran, where ground troops would be needed, there is no guarantee America would win, they add.)

A new sub-war of the War on Terror is now closer than it has been in living memory. And the U.S. is ready. Per capita military spending has increased by 48 per cent since Sept. 11, 2001. Every man, woman and child in America now spends US$700 more every year to fund the military. After 18 years of perpetual war, the U.S. is also awash with military-grade weaponry. Trump has ordered more of it to be delivered to local police forces, transforming them from engaged members of a community into what looks suspiciously like a police state.

Security laws passed shortly after 9/11 have added legal muscle to the lethal hardware, further undermining social cohesion and turning up the dial on fear. Democracy, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit, has faded, with the U.S. ranking as a “flawed democracy” for the past three years running.

The irony is that in responding to the attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, America handed al-Qaeda its first, and arguably most substantial, victory. When Osama bin Laden dispatched four airliners on a mission to strike a blow to the heart of its arch-enemy’s base of power, he was following a strategy that had been in the making for years. And the results—dominoes falling in favour of extremism—have played out better than he ever thought possible.

***

On Dec. 14, 1999, when Ahmed Ressam set off from Vancouver to Los Angeles International Airport, his rented Chrysler sedan packed with explosives, he was setting the groundwork for what would become a template for terrorism in the 21st century.

Just over a year earlier, in February 1998, bin Laden had issued his second fatwa. The first, in 1996, had declared a holy war on the U.S.; the second expanded that war, declaring that killing Americans “is an individual duty for every Muslim who can do it in any country in which it is possible to do it.”

Ressam was one of the first to heed bin Laden’s call and, if not for a keen-eyed customs officer at the U.S. border crossing in Washington State, he likely would have succeeded.

When bin Laden declared war on America, jihadists in the Middle East were still struggling to find a purpose after the victory over the Soviets in Afghanistan. Debates over what to do next had been raging for nearly a decade, with some arguing for the overthrow of corrupt Arab regimes and others, headed by bin Laden, staking out the position that those regimes were too well-financed by western nations—primarily the U.S.—and the best strategy was to target those backers.

Bin Laden and his fighters were often ridiculed by the Afghan mujahedeen for lacking their courage and fighting prowess. But the 1998 fatwa proved to be a stroke of genius. Within months, al-Qaeda carried out coordinated attacks on U.S. embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, killing 224, including 12 Americans. A year later, a second attack targeted the USS Cole, a guided missile destroyer refuelling in Yemen’s Aden harbour, killing 17 sailors and injuring 39 others. Jihadists in the Middle East, and aspiring radicals around the world, took notice and flooded into al-Qaeda’s camps.

Ressam’s plan to attack the airport fell on a continuum of attacks designed to “lure the United States into Afghanistan,” Lawrence Wright argued in his 2006 Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Looming Tower. “The usual object of terror,” he continued, “is to draw one’s opponent into repressive blunders, and bin Laden caught America at a vulnerable and unfortunate moment in its history.”

Indeed, America wasn’t the only vulnerable one. The 1990s had been a difficult decade for Muslims around the world. Extremism, never more than a fringe movement in the history of Islam, was on the rise. With the end of the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan in 1989, thousands of jihadists from around the world were left without a war to fight. Some tried to return to their home countries but were rejected by their governments, who feared their radicalism. Many settled in Pakistan along the Afghan border, putting the onus on Pakistan to deal with them.

When the Kashmir insurgency kicked off in India in 1989, the Pakistanis, keen to re-direct the jihadi war machine they had inherited, began deploying veterans of the Afghan jihad to Kashmir, transforming what had largely been a peaceful movement for self-determination into a full-blown holy war.

Meanwhile in Europe, another menace was stirring as fascist and white supremacist movements saw an opportunity. They borrowed heavily from leftist laments over working-class suffering and reframed the narrative of economic hardship as the inevitable consequence of mass migration and the erosion of “European” culture.

When al-Qaeda struck in New York and Washington, it struck at a time when the world was a tinderbox. It’s hard to know whether bin Laden was aware of just how perfect his timing was, but the scale of attacks and the dramatic images beamed live around the world sparked a series of events that played into al-Qaeda’s plans. It was division and chaos they were after, and they got it.

***

On Sept. 20, 2001, President George W. Bush walked into a packed House Chamber in Washington to deliver his first substantive speech after the attacks of September 11 at a joint session of Congress. Only eight months into his first term, he arrived to bipartisan applause and waded somewhat dazedly through the crowd, greeted with firm handshakes and vigorous shoulder grabs.

Bush devoted many of his words to the acts of courage and resilience Americans had shown and to the unity America’s allies had demonstrated. But then he laid out how the U.S. would respond. The attacks, he declared, were an act of war unlike any other war America had experienced in its admittedly war-plagued history. “Our War on Terror begins with al-Qaeda,” he said, “but it does not end there. It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated.”

Bush was careful to point out that the War on Terror was not a war on Islam. But in the weeks and months that followed, it increasingly looked as if it was.

During his speech, he announced the establishment of the Office of Homeland Security; a month later, the U.S. Congress passed the Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act of 2001, better known by its acronym, the USA PATRIOT Act. The use of mass surveillance by the National Security Agency, made possible by the Act and publicly disclosed by Edward Snowden in 2013, showed the degree to which safeguards meant to contain the activities of intelligence agencies had eroded, not only in the U.S. but also in Canada and other western nations.

The “repressive blunders” Wright had highlighted in 2006 were, seven years later, more widespread than he could have imagined. And in other parts of the world, they were about to get worse.

China, struggling to tamp down on the violent response to its repressive policies against its Muslim Uighurs, embraced the War on Terror with the kind of zealotry that only a paranoid authoritarian regime can muster. An estimated one million Uighurs, the majority ethnicity in China’s northwestern Xinjiang province, are now locked up in what China calls voluntary re-education centres. Tens of thousands have fled to Turkey where they have set up a de facto exiled “East Turkestan,” the name Uighurs use for their historic homeland.

“This Uighur ‘problem’ has been around for decades,” says Abdul Hafiz Makhdum, a member of the East Turkestan Ulama Council, a group of Uighur religious scholars that runs a network of schools in Turkey. “Uighurs have been oppressed in China since before the Cultural Revolution. Our young people never became radicalized. But since September 11, it has been different. The Chinese regime began cracking down harder. And since Xi Jinping became president, it has gotten worse.”

READ MORE: China’s disregard for the rule of law strikes too close to home

The East Turkestan Islamic Movement, an al-Qaeda–aligned group, remains active in the Syrian war. Makhdum and his council have been confronted by ISIS recruiters trying to convince them to hand over their young men and boys for jihad. “Our young people are susceptible,” Makhdum says. “Xi’s goal is to wipe out the Uighur identity. Everyone has someone who has disappeared into these camps. Al-Qaeda and ISIS promise revenge, so of course they are tempted.”

Xi is only the most egregious example of an authoritarian leader who capitalized on the War on Terror to promote his nationalist policies. Narendra Modi in India who, prior to September 11, had been a far-right Hindu activist with no governing experience, rode the wave of anti-Muslim sentiment that grew out of the Kashmir insurgency to become prime minister. In Europe, far-right nationalists also latched onto anti-Muslim momentum to lift themselves tantalizingly close to the kind of support they enjoyed during the heyday of fascism preceding the Second World War.

Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, Mohammad bin Salman in Saudi Arabia, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in Egypt, and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil—all U.S. allies—owe their political fortunes in one way or another to the War on Terror.

***

Defenders of American strategy point to al-Qaeda’s inability to strike again at the U.S. homeland. Everything that has happened in America since September 11—the wars, the counterterrorism operations (both domestic and international), the birth of security agencies like Homeland Security and ICE—have kept America safe, they say.

From a security perspective, the numbers don’t lie. The number of Islamist-led terrorist incidents on American soil have dropped dramatically since 2015, in large part because of the nearly US$3 trillion the U.S. spent on counterterrorism efforts from 9/11 to 2017.

“The limited threat to the United States is in large part the result of the enormous investment the country has made in strengthening its defences against terrorism in the post-9/11 era,” the authors of a September 2019 report on terrorism in America, published by the New America think tank, concluded.

Al-Qaeda sees victory very differently. From its perspective, much of what America has done to ensure its own security plays directly into its long-term plans. The setting up of new departments like Homeland Security, the rise of mass surveillance and the arming of local police forces with military-grade weapons—it all signals a decay at the heart of American democracy: a rot if not set in motion by the attacks on September 11, then at the very least accelerated by them.

Nicolas Johnston and Srinjoy Bose argue in their Jan. 22 research paper, published in the journal Global Policy, that a better way to measure who is winning or losing the war is to look at how democratic institutions have been affected by it. From that perspective, al-Qaeda has succeeded in its goals. “Terrorism cannot create its own legitimacy,” they write, “it seeks to undermine that of the state by encouraging it to commit its own excesses in retaliation.”

In other respects, al-Qaeda is clearly losing: Muslims around the world, for instance, are not flocking to the cause; they are instead rejecting it en masse. The al-Qaeda leadership has been sensitive to this, shifting its tactics in 2013 to try to minimize civilian casualties and even admitting to mistakes when innocents have been killed. Indeed, distancing itself from ISIS was part of that rebranding strategy.

FROM THE ARCHIVES: Al-Qaeda rising

Al-Qaeda, of course, will likely never succeed in its ultimate goal of setting up a global caliphate. But that’s not really the point. The damage it does to our own societies in the process is what will have the most profound effect for the future. That reality is dawning on some former senior officials in the U.S.

In a December interview on the Pod Save the World podcast, Jeff Eggers, a former U.S. Navy Seal and the National Security Council’s senior director for Afghanistan and Pakistan during the Obama administration, looking back on everything the U.S. has done since 9/11, asked: “What does it mean to win? In American culture, and doubly so in American military culture, we’re very action-oriented. We tend to define success as the achievement of our objectives. But there is a way of thinking, militarily particularly, that success can also be achieved by denying your adversary their objectives. In this case, we probably would’ve been a lot better off if we had just occasionally reminded ourselves of that inverse formulation, which is to say: what if al-Qaeda’s goal here is not to defeat the United States militarily, because clearly that’s never going to happen. What if al-Qaeda’s goal is to drag us into a protracted set of wars in the Middle East that will bleed us economically? If you flip it around from that point of view, then your bias is not going to be toward escalation; your bias is actually going to be toward de-escalation, to deny al-Qaeda what it is they’re trying to do.”

But is it now too late? De-escalation is not in Donald Trump’s vocabulary. And who could have anticipated a U.S. president who would so gleefully work to torpedo any efforts at diplomacy with enemies and allies alike, who would fan the flames of war with Iran?

Al-Qaeda’s ultimate goal is to make Muslims feel isolated and under attack. It wants to spark a war between the U.S. and Iran and set the stage for broader global conflicts. And it is now closer to “mission accomplished” than America has ever been.

This article appears in print in the April 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “The terrorists won.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.