The trouble with ‘Kony 2012’

Celebrated Canadian author M.G. VASSANJI on Africa’s missing voice in the viral video media storm

Share

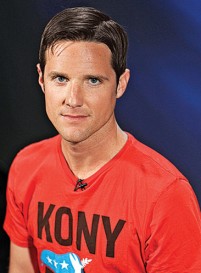

Kony 2012, the YouTube film about the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in Central Africa and its leader, Joseph Kony, took the world—at least that portion connected by social media—by storm. Celebrities such as Oprah Winfrey, Mia Farrow, and Rihanna went on Twitter to show their support, and within a few days the video had attracted tens of millions of views and garnered large donations for its creator, the U.S.-based charity Invisible Children. Admittedly, much of the media analysis was about how the video actually went viral—apparently we are still in the midst of euphoria about the miracles of social media. No one quite understands the storm; perhaps there was a lull in the news that the short video filled; it was well-made, with a simple message: unless we act, Kony’s crimes against humanity will go on. America, especially, and youth in particular, were awakened.

The LRA is accused of mass atrocities, including brutal killings, sexual slavery of young women and turning boys into killers. Surely there’s nothing too remarkable about this. We have become used to atrocities in Africa—only a few months ago we were told of rapes and kidnappings in the Congo. Who can forget Rwanda? There were the child soldiers and amputations during the civil wars of Sierra Leone and Liberia, and the decades-long war in Angola that left thousands maimed. And so on. And, to be fair, it’s not only Africa that’s capable of atrocities. We had the mass killings of Cambodia; there was Iraq. One feels helpless and bewildered.

There were, of course, immediate objections to the video—its manipulative inaccuracies and timing, its open call for a larger American intervention (a small force of military advisers is on the ground), its missionary tone and simple-mindedness (“pitched to a five-year-old’s sense of right and wrong,” according to a New York Times column). Yet no one could deny that it had brought the evil Joseph Kony to world attention.

What woke me up from my depressive apathy on this subject was one sole news item that reported selected African criticisms of Kony 2012, to which I found myself saying “hurrah,” and “at last.” Suddenly—to interpret these Africans’ responses—their part of the world was in the news; millions in the West talked and read about it, pitied it, and blogged and tweeted about saving it. But where in this narrative, these critics asked, was Africa’s own voice, except as a helpless victim?

Rosebell Kagumire, a Ugandan blogger, observed, “this is another video where I see an outsider trying to be a hero rescuing African children. We have seen these stories a lot in Ethiopia, celebrities coming in Somalia.” The film only furthers “that narrative about Africans: totally unable to help themselves and needing outside help all the time.” Another blogger, TMS Ruge, wrote, “Africa is our problem, we hereby respectfully request you let us handle our own matters. If you really want to help, keep the guilt and charity in your backyard. Bring instead, respect, and the humility to let us determine our destiny.” And novelist Teju Cole tweeted provocatively about “the banality of sentimentality” and the “White Saviour Industrial Complex.” Others saw a “white man’s burden” message repropagated.

I cannot help but applaud these sentiments, even if some of them seem over the top. They are a shot in the arm. More Africans should raise their voices to tell their own stories, and object to being treated merely as abject victims. For Africans—my own ancestry is Indo-African—depictions such as Kony 2012 are deeply humiliating, often offensive. It is the outsiders who write these narratives of hunger, war, need; self-appointed specialists zealously hop from one horror to another, reporting them in graphic detail. For them, normal life does not exist in Africa—not the markets, the schools and games, the weddings and festivals. And yet, having said that, who would deny that the terrible realities they depict actually exist? And there is an unnerving sense of irony in all this: how to reconcile “Africa is our problem” with the sad truth that much of Africa depends on foreign aid, like a patient permanently on life support. NGOs keep mushrooming, providing social services and jobs. In Dar es Salaam, where I grew up and often visit, it’s difficult to come across people who do not depend on some foreign connection for their living.

But these African responses to Kony 2012 raised a faint hope. The video may awaken the West to Kony and his like, but perhaps it will awaken younger Africans to themselves. They should proudly speak for Africa, yes, but they should also be the generation that moves it toward real independence. M.G. VASSANJI

* M.G. Vassanji’s new novel, The Magic of Saida, will be published in the fall.