Why Canada should return to Afghanistan

Adnan R. Khan: The Iraq mission wasn’t all it was pumped up to be. In retrospect, Canada shouldn’t have left Afghanistan, which badly needs help.

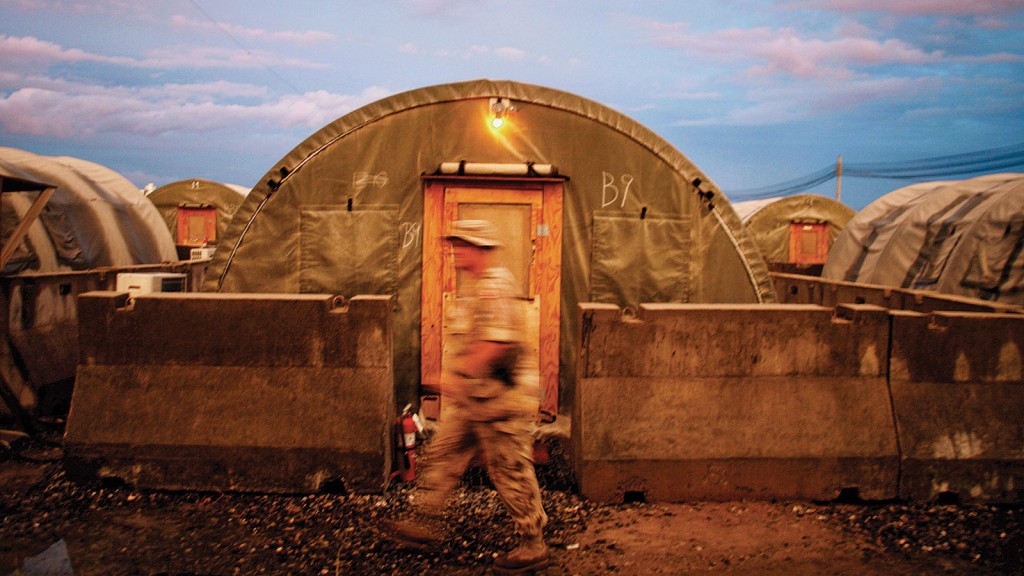

Finbarr O’Reilly

Share

In April 2016, while on a tour of the frontlines in the fight against the so-called Islamic State in Iraq’s Kurdistan Region, General Jonathan Vance, Chief of Defence Staff of the Canadian armed forces, made forceful pitch for why Canada needed to train Iraq’s Kurds.

“I believe [the offensive to re-take] Mosul will start this year,” he told CTV News. “The Zeravani commando isn’t formed yet. So as we form it and train it, they’ll have the weapons necessary to do the job they need to do. When the campaign to re-take Mosul will start and end, it would be ideal if we have the Zeravani commando ready for operations.”

Vance was referring to the Kurdish forces that were receiving the bulk of the training and assistance Canada’s Special Operations Forces had been providing since 2014. At the time, the Zeravani were expected to be at the forefront of the impending battle for Mosul. After withdrawing Canadian fighter jets from the international coalition in February 2016, the Liberal government had doubled-down on the Kurds, announcing it would send an additional 200 special forces to the region with the express mission of getting the Zeravani ready for what everyone knew would be a brutal fight.

It seemed like a prudent decision. Since it emerged in 2014, ISIS had proven itself to be the most dangerous terrorist group the world had ever seen. It had injected new blood into the global jihadist movement, attracting unprecedented recruits who either joined the group in Syria and Iraq or were inspired to carry out devastating attacks at home.

Mosul was its crown jewel, the place where its leader, Abu Bakr al Baghdadi, had declared a caliphate and the largest city under its control, with an estimated population of one million. Retaking Mosul would deal a near-fatal blow to the movement.

Meanwhile, in March 2014, Canada had officially ended its military mission to Afghanistan after 12 years and 158 dead soldiers. It was a bitter-sweet end to a mission that had pushed Canada into territory it had not ventured into since the Korean War: direct involvement in war fighting. Canadians had fought bravely in Kandahar, despite the overwhelming odds stacked against them. They had built up a reputation for fielding one of the best-trained militaries in the world.

By 2014, however, that mission had been reduced to a small contingent tasked with training Afghan security forces and was floundering in obscurity.

Under the Harper Conservatives, Canada’s military sights had begun to drift westward in 2011, away from Afghanistan and toward the Arab Spring in the Middle East and the conflicts arising from it. The Conservatives, with an almost obsessive focus on terrorism, had decided to go all-in, playing a key role in the mission to topple the Ghaddafi regime in Libya and, at least initially, supporting the Syrian opposition against Bashar al Assad.

History will judge the wisdom of those decisions but the early signs are discouraging. From 2011 onward, Canada’s stated mission—assisting democratic movements in the region—collided with the complexities of nation building. Libya fractured into mini-states ruled by tribal militias. Syria devolved into a civil war pitting dozens of armed groups against each other. By the fall of 2014, as ISIS rose out of the ashes of the Syrian civil war, the Conservatives shifted their focus again.

“Let me be clear on the objectives of this intervention,” Harper said of the decision to deploy special forces trainers, along with the fighter jets, to Iraq in a speech to parliament in early October 2014. “We intend to significantly degrade the capabilities of ISIL… Specifically, its ability either to engage in military movements of scale or to operate bases in the open.”

At the same time, the breakdown of security in Afghanistan had accelerated, particularly after the U.S. pulled its troops later in October. Many started to see Afghanistan as a lost cause, despite the significant progress that had been made in developing the country’s infrastructure and institutions.

Was this Canada’s WMD moment? In 2003, the U.S. under George W. Bush turned away from Afghanistan and poured its military resources into Iraq. The shift is now blamed for giving the Taliban the time it needed to regroup and rebound as an insurgent movement. Bush’s cohorts in the Republican Party initially used the spectre of weapons of mass destruction as justification for the shift. When those failed to turn up, it recast Iraq as a mission to bring democracy to the Middle East.

Canada has also struggled to find meaning in its Middle East pivot. Democracy in Libya, Syria and Egypt appears further away today than ever and even though the mission to destroy ISIS is succeeding, Canada’s contribution to the fight is looking more and more superficial.

Initially, things were going according to plan. The expertise Canadian special forces brought to the table was a valuable asset to the Kurds. While other NATO countries provided training to the Kurdish Peshmerga in purpose-built centres scattered around the Kurdistan Region, the Canadians embedded with Zeravani forces on the ground, at or near the frontlines, providing real-time guidance and support in real-life combat situations.

Not surprisingly, the Zeravani were transformed into a capable fighting force, arguably the best fighters Kurdistan now fields. They took the lead at the launch of the Mosul offensive in October last year, punching through ISIS frontlines and retaking territory north and east of the city. And Canadians were right there with them.

But then they stopped. In a deal brokered with Iraq’s central government, the Kurds agreed not to fight in Mosul. Instead, they set up their own positions kilometers away, watching as elite fighters from the Iraqi special forces confronted the bulk of ISIS forces.

Compared to what the Iraqis faced inside the city, the Kurdish advance was a cakewalk. The initial resistance they met collapsed quickly as ISIS fighters retreated to Mosul and dug in for the gruelling battles to come. Airstrikes helped the Kurds roll through largely emptied towns and villages and avoid the kinds of street-by-street, house-by-house confrontations the Iraqis would have to contend with.

Politically, things were not much better. Canada’s train and assist mission had a destabilizing effect on the Kurdistan Region. The focus on the Zeravani, a specialized commando force attached to the Interior Ministry, angered some Kurdish politicians. The ministry, like many of Kurdistan’s power centres, is controlled by the dominant Kurdistan Democratic Party, a family affair run by the Barzani clan. Opposition parties, and some Canadian diplomats, complained to Maclean’s in 2015 that Canada, under the Harper Conservatives, was favouring one political party and, perhaps unwittingly, playing into the deep-rooted Kurdish divides that have plagued the region for decades.

More broadly, the support for the Kurds ratcheted up tensions with Baghdad, which accused foreign governments like Canada of stoking Kurdistan’s independence aspirations. In June, Kurdistan’s president Masoud Barzani announced a non-binding referendum on independence scheduled for Sept. 25, raising concerns that Canada may have armed and trained the military of a future breakaway state.

The Liberal government now appears to be coming around to the problems associated with supporting the Kurds. In March, Canada’s special forces shifted some of their focus to helping the Iraqi army in Mosul and a February 2016 deal to provide weapons to the Kurdish Peshmerga has been put on hold indefinitely.

Still, the grand vision articulated by Harper, and later by General Vance, where Canadian-trained Zeravani commandoes would take the fight to the Islamic State, largely came to naught. In the process, Canada abandoned a mission in Afghanistan in which it had invested millions of dollars and where Canadians had sacrificed their lives.

Chris Kilford, a retired Canadian artillery officer and now a fellow at the Queen’s University Centre for International and Defence Policy, argues that Canada’s turn to the Middle East was probably inevitable given the public fatigue over the war in Afghanistan. And neither the Harper government nor the Liberals, he adds, could have predicted how events would unfold in Mosul.

“Should we have left [Afghanistan] when we did?” he says. “No. Should we still have trainers on the ground? Yes. But we have a bit of momentum now. We’ve put a lid on this massive issue known as the Islamic State. We can turn our attention to other places such as Mali, Libya and Afghanistan.”

It’s impossible to judge if Afghanistan would be different today if, instead of pulling trainers out, Canada had sent its special forces there instead of Iraq. What’s certain is that Afghan security forces have come to rely on their own special forces, largely trained by the U.S., to take the fight to the Taliban. According to Afghan defense ministry officials, their special forces only make up seven per cent of the Afghan military but have led 80 per cent of offensives. U.S. commanders say they are the most successful fighters on the battlefield, but they are being pushed to their limits.

Earlier this year, President Ashraf Ghani announced a plan to double the existing 17,000 special forces troops over the next four years. Kilford warns such an expansion will require a massive mobilization of resources.

“In Canada, the Liberals have decided to increase special forces personnel by around 600 over the coming years,” he says. “That means taking on around 1,800 recruits and whittling them down to the best.”

It was a mistake to turn away from Afghanistan and Afghans have paid the price for it. Canada should not compound the mistake by continuing to withhold the support the Afghan military needs at a time when successes in Afghanistan hangs precariously in the balance.

Training for the Kurds has only produced elite fighters without a war to fight. In Afghanistan, the war is still raging. And they need Canada’s help.