Donald Trump has congressional immunity. Yes or no?

Alan Dershowitz responds to Laurence Tribe. As the temperature rises in the Russia investigation, constitutional experts face off.

US President Donald Trump walks towards Air Force One to board the plane at Morristown Municipal Airport on September 22, 2017 in Morristown, New Jersey.

Trump is on his way to Huntsville, Alabama, where he will speak at a rally for Sen. Luther Strange. (Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images)

Share

My colleague Larry Tribe’s response is unfortunately not responsive to my arguments. He erects several straw men, which he proceeds to knock down, but he fails to respond to my most compelling arguments.

Two striking examples: Larry correctly points out that congressional immunity is based explicitly on the text of the Constitution, but he fails to deal with my other primary example—judicial immunity. There is no mention of judicial immunity in the Constitution, and yet the Supreme Court has ruled that the separation of powers and checks and balances requires that judges be immune for conduct that is part of their constitutionally authorized powers. If he is to argue that the inclusion of congressional immunity in the Constitution precludes immunity for members of other branches, he must respond to my argument about judicial immunity. That he fails to do so reveals the weakness in his constitutional analysis.

Follow the full exchange in Maclean’s:

- ALAN DERSHOWITZ: Why Trump cannot be charged with obstruction

- LAURENCE TRIBE: Why Trump can be charged with obstruction

Second, I provide three specific examples of presidential acts that he ignores: President George H.W. Bush was neither charged nor impeached for pardoning Casper Weinberger and other potential witnesses against him—acts that the special prosecutor believed were clearly motivated by a desire to protect himself. Nor does he deal with the fact that presidents Nixon and Clinton were not impeached for merely exercising their constitutional authority. Congressional committees went out of their way to specify criminal acts beyond those authorized by Article II. Larry must deal with these examples. While doing so, he may also want to consider the failed impeachment of former president Andrew Johnson for firing a Cabinet member in violation of the Tenure of Office act passed by Congress. The Supreme Court ultimately held that act unconstitutional as violative of separation of powers.

The cases Larry cites do not deal directly with the issue of whether a president can be charged with criminal conduct for merely exercising his Constitutional powers. His inclusion of impeachment is yet another straw man, since my article does not suggest that a president could not be impeached for improperly pardoning or firing an executive official. That remains an open question. The text of the Constitution suggests that impeachment must be based on “treason, bribery or other high crimes or misdemeanors,” but Congress may have the power to broaden these categories.

Larry includes among alleged criminal acts by President Trump telling the director of the FBI to go easy on General Flynn. But he fails to respond to my more general point that our Constitution authorizes the president to direct his attorney general who to prosecute and who not to prosecute. Thomas Jefferson did that, as did Abraham Lincoln, FDR, and Barack Obama.

Larry’s most dangerous argument—and several of his arguments endanger our liberties—is that “placing presidential pride over the nation’s sovereignty is a grave abuse of presidential power by anyone’s definition.” All presidents are motivated in part by “pride” and other personal considerations. If questionable motives could turn an Article II exercise of presidential power into crimes, there would be no limits to the criminalization of political differences.

Finally, Larry characterizes my arguments as “familiar,” as if that were a bad thing. He is, of course, correct about them being familiar since I have been making them for nearly 50 years. I opposed the naming of Richard Nixon as an unindicted co-conspirator. I railed against the impeachment and prosecution of former president Clinton. And I strongly opposed efforts to criminalize Hillary Clinton’s carelessness. Yes, my arguments are familiar because I have been consistent in making them for half a century. They are not about Donald Trump. They are about the institution of the presidency and our constitutional system of separation of powers and checks and balances.

This exchange demonstrates that Larry Tribe and I respectfully disagree about fundamental issues regarding our Constitution and efforts to criminalize political conduct. I think the general public can learn from our clash of ideas. Accordingly, I renew my challenge to my friend and colleague to engage in a public debate now while these important issues are at the forefront of public controversy. CNN has offered an international platform for this debate. I have accepted CNN’s invitation. I urge Larry to do so as well, so that we can respond to each other’s arguments in the court of public opinion. And let the citizens decide. That’s how democracy works best.

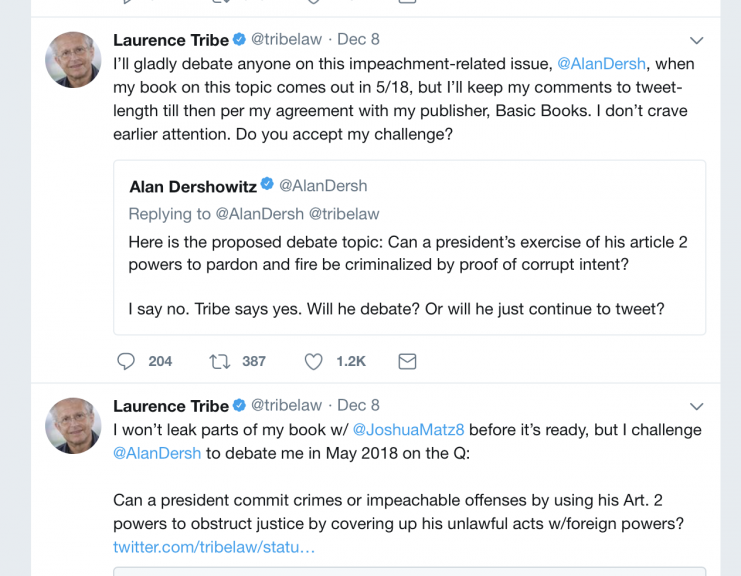

Editor’s Note: Mr. Tribe has already publicly offered via Twitter to debate Mr. Dershowitz, but not before May when his book To End a Presidency: The Power of Impeachment is due to be published. He says the offer stands.

MORE ABOUT DONALD TRUMP:

- If you only read one book about Trump over the holidays, make it this one

- Why Donald Trump can be charged with obstruction

- Why Donald Trump can’t be charged with obstruction

- Fascism’s return and Trump’s war on youth

- ‘Why are fidget spinners so popular?’ What Canadians searched on Google in 2017

- Democrat Doug Jones defeats Roy Moore in Alabama Senate upset

- Donald Trump and North Korea’s nuclear war rhetoric is frighteningly similar