How Donald Trump’s past with pro football revealed his true self

Opinion: As the President takes aim at NFL players for taking a knee, Jeff Pearlman finds clues of the present in Trump’s past as a USFL team owner

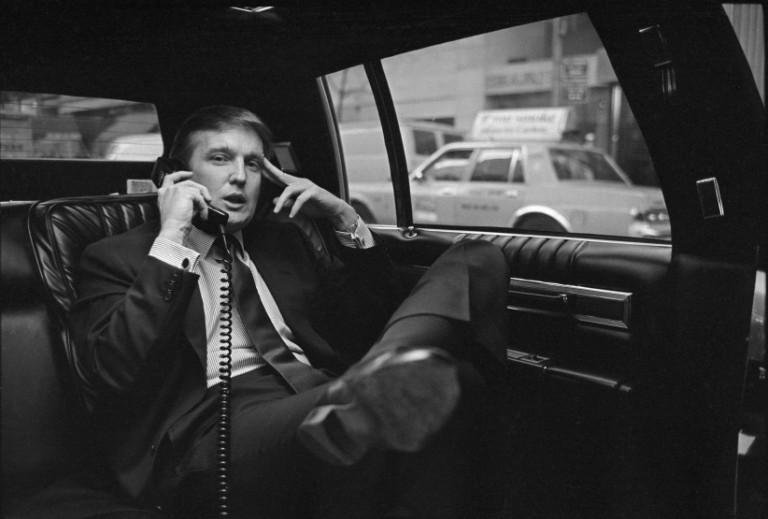

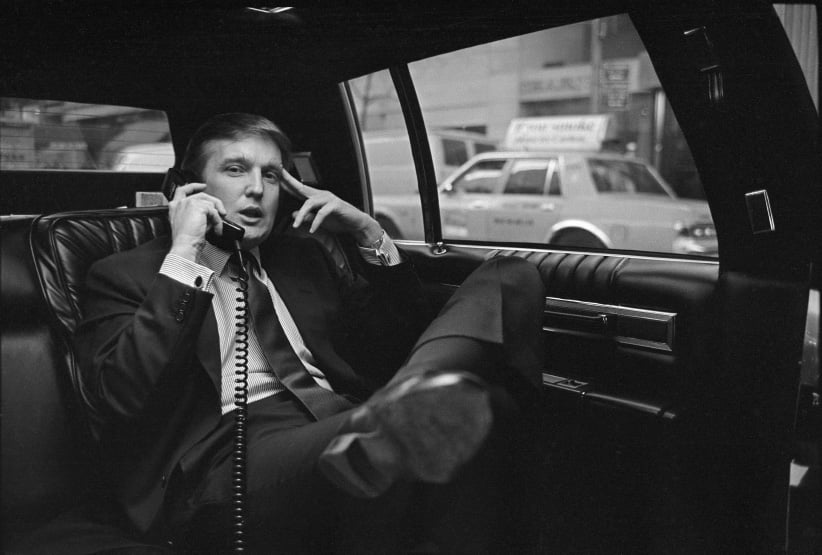

Donald Trump on the phone in his car after announcing plans for development of the west side of midtown Manhattan at the Hyatt Hotel on 42nd Street and Lexington Avenue, in New York, NY, November 18, 1985. (Neal Boenzi/The New York Times/Redux)

Share

Jeff Pearlman is the author of multiple New York Times bestsellers. You can follow him on Twitter @JeffPearlman and listen to his podcast, Two Writers Slinging Yang, here.

The greatest letter humanity may ever see is dated August 16, 1984.

It was written by John Bassett, the Canadian businessman who owned the Tampa Bay Bandits of the United States Football League, which played its games in the spring and was then in its second year. I uncovered it about a year ago, while researching The Useless, my upcoming book about the USFL.

The note’s purpose: To express extreme displeasure.

The note’s destination: The offices of one Donald J. Trump.

At the time, the man who would become America’s 45th president was merely a New York real estate developer and the owner of the USFL’s New Jersey Generals. He had purchased the organization earlier that year, and following a whirlwind of big-money signings, helped the team improve from 6-12 in 1983 to 14-4 one season later. Trump was bold and brash and dashing, a big figure in a still nascent league.

“Dear Donald.”

The letter begins peacefully enough. Bassett devotes a full paragraph to praising Trump’s business acumen, noting that “you are a talented and successful young man.” He even calls Trump “a friend and an owner who has made a contribution to the league in general and been a saviour to New York/New Jersey in particular.” Then—the hammer.

Writes Bassett: “While others may be able to let your insensitive and denigrating comments pass, I no longer will. You are bigger, younger, and stronger than I, which means I’ll have no regrets whatsoever punching you right in the mouth the next time an instance occurs where you personally scorn me, or anyone else, who does not happen to salute and dance to your tune.” Bam.

Long before the United States’ electoral college system gifted the world with the greatest conman of the past half-century, and before he took aim at players in the National Football League and National Basketball Association, Trump exposed his true self via professional sports. When he paid US$9 million (not the $5 million he boasted to people) to buy the Generals from an Oklahoma oilman named J. Walter Duncan after the 1983 season, Trump insisted that he loved the USFL, that he dug spring football, that this was a concept he believed in and a product that could last. “He was the air pump into the tire,” Charley Steiner, the Generals play-by-play announcer, once told the Washington Post. “He gave the league the air it needed, elevated it to another level, pumped it up real good.”

MORE: Scott Gilmore on Trump, taking a knee, and the meaning of patriotism

As soon as the acquisition was finalized, however, the real Donald Trump stepped forward to breathe fire. The USFL, he maintained to anyone with working ears, was a rinky-dink operation that would never rival the NFL until it switched from spring to fall to battle the elder league head-to-head. “If God wanted football in the spring,” he famously said, “he wouldn’t have created baseball.” During owner meetings, he bullied, he mocked, he ridiculed, he insulted—all in an effort to get his peers to agree with him. He told the other owners that great riches awaited in the fall; that the USFL would either beat the NFL or, worst-case scenario, be absorbed by the NFL. When Chet Simmons, the famed television executive who served as the league’s first commissioner, resisted the move-to-fall bluster, Trump attacked him in the newspapers, often cloaked by anonymity. Ultimately, he forced Simmons’ ousting.

And, of course, there were those “insensitive and denigrating comments” that Trump slung at Bassett, one of the few men who smelled Trump’s nonsense from afar. If owners and executives took time to read between the lines, it was clear Trump was angling for a merger between the leagues, with the goal of the Generals becoming the NFL’s lone New York City-based franchise. Few, however, read between the lines. Trump was young (he was 37 at the time) and—to the unsophisticated and easily swayed—convincing. He spoke, and people followed. He promised, and people believed.

In 1984, the USFL announced a two-pronged plan to switch to the fall in 1986 while also filing a US$1.69-billion lawsuit against the NFL for violating antitrust law by monopolizing sports television. Trump led the way in hiring the USFL’s attorneys and developing a scorch-the-earth approach.

The result: The USFL won the case, but—with a jury uninspired by the loudmouth Generals owner and his arrogant testimony—was awarded a mere $1 in damages. The league vanished, never to be heard from again.

Thirty-one years later, Donald Trump discusses the USFL about as willingly as he discusses hemorrhoid cream or life with Marla Maples. It is the blackest cloud on a resume filled with black clouds, a reminder that the so-called “dealmaker” singlehandedly worked to destroy a promising league.

When, in 2009, the filmmaker Mike Tollin interviewed Trump for the ESPN documentary Small Potatoes: Who killed the USFL?, the billionaire sat in a chair and fielded questions with the joy of fielding dead rodents. After the film aired, Tollin—who had created the USFL’s weekly highlight show decades earlier—received a letter from Trump. “MIKE: A THIRD-RATE DOCUMENTARY—AND EXTREMELY DISHONEST (AS YOU KNOW) BEST WISHES, DONALD TRUMP PS: YOU ARE A LOSER.”

“That’s Donald Trump,” Tollin told me. “It was him in the 1980s, it’s him now.”

Indeed. The warped lesson of those football days is that, with enough swagger and gusto, anyone can be bullied. The Trump who mocked Bassett is the Trump who mocks Kim Jong Un. The Trump who convinced the USFL’s other wealthy owners to follow him and move to fall is the Trump who convinced rural white Americans that a former Democrat with five military draft deferments and a $3.7-billion net worth is one of them.

The United States Football League failed to last. But Trump’s trademark bombast and nastiness began in the world of spring gridiron.

For the USFL, it’s not a legacy to boast of. But it is, without question, a legacy.

RELATED:

MORE ABOUT DONALD TRUMP:

- #TakeAKnee tweets massively outnumber #BoycottNFL tweets

- Two nuclear hotheads and a job for Justin Trudeau

- Ivanka Trump’s Chinese business ties shrouded in secrecy

- To sit or stand? It’s Sunday night in the NFL.

- Trump, taking a knee in the NFL and the true meaning of patriotism

- U.S. flies bomber, fighter mission off coast of North Korea

- ‘Deranged’ Trump will ‘pay dearly’ for threats, says Kim Jong Un

- Trump speech a ‘welcome statement,’ says Russia foreign minister