How we chose the entries for our 2022 Power List

Our Editorial: The thinking behind our annual ranking, which reflects the pressing issues facing the country, and the opportunities ahead

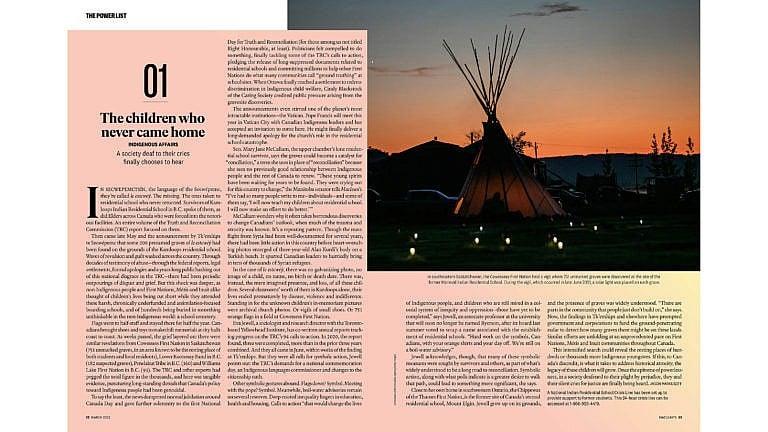

#01 of the Maclean’s 2022 Power List: The children who never came home.

Share

In 2021, amid report after report of presumed grave sites being found on the former grounds of residential schools, non-Indigenous Canadians experienced what’s been generously described as an awakening. Everyone from random citizens doing TV street interviews to the Prime Minister himself voiced horror and dismay, as if blindsided by the fact that the assimilationist project this country ran for the better part of a century had claimed the lives of children. Many, many children.

We were not, of course. The deaths of young Indigenous kids at residential schools were described widely in the accounts of former students, who shared the knowledge with their children and grandchildren; they were meticulously reported by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2015.

THE POWER LIST: See the full ranking of 50 Canadians

No wonder, then, that as the news sank in, a strikingly different theme emerged in the remarks of Indigenous leaders. If Canada had indeed awakened, they asked, would it now act? Or would it leave First Nations people to keep curating this dreadful history, passing it between generations in the hope that someday, at long last, it would move their non-Indigenous neighbours to repair a broken relationship?

Cadmus Delorme, the chief of the Cowessess First Nation in Saskatchewan, put it best: “We have one of two options right now,” he told Global News in November. “To address the truth, accept the truth, then move to reconciliation; or be ignorant to the reality and make our children figure it out. I am one to not wait for our children to figure it out.”

Write it in the sky. Again and again, Indigenous children have borne the brunt of tragically misguided government policy. Over successive generations, they were abused in the schools and exposed to disease, plucked from their loved ones to be raised by white families and traumatized by intergenerational fallout. For decades, they’ve been voiceless and forgotten. Surely this moment of self-realization is our chance to change that.

RELATED: We failed to hear them when they lived. We are obliged to hear them now.

Here, in brief, is the thinking behind our decision to place the unknown victims of residential schools at the top of our annual Power List (page 30). The children who rest in graves at Tk’emlúps, Cowessess, Williams Lake, B.C., and elsewhere are lost to their communities. But the shared knowledge of their existence, of their fates, has its own compelling power. We failed to hear them when they lived. Without question, we are obliged to hear them now.

Before making this choice, Maclean’s consulted privately with Indigenous, Métis and Inuit leaders, who unanimously approved of, and in some cases applauded, the idea. The grave finds, they agreed, changed the tone and substance of debate over Indigenous rights. Whether that change yields action, they’re waiting to see. But it has already proved pivotal in forcing Ottawa to negotiate its landmark $40-billion settlement on Indigenous child welfare.

To be heard is to have influence, so this year’s ranking also features a number of prominent First Nations people to whom the country has turned its ear—RoseAnne Archibald, the first woman to lead the Assembly of First Nations; Niigaan Sinclair, a writer, political commentator and community activist; and Autumn Peltier, the water defender, among them.

As in 2021, our ranking hews toward good-faith actors in the service of positive change, even if their approaches, or their notions of positive, are not universally shared. Pierre Poilievre is not every Canadian’s first choice as a seatmate on a long flight. But the Tory MP excels in his role as an opposition critic, holding the government’s feet to the fire.

And again, we’ve looked beyond mere status. The nabobs of banking, lobbying, telecom and other arms of the establishment must do more than occupy corner offices to merit berths on our ranking. Simply making noise in the town square isn’t enough, either. Dog-whistlers, conspiracy theorists and censorious pedants are ineligible.

The result, we believe, is a ranking that reflects the pressing issues facing the country, and the opportunities ahead. Attentive readers will notice that Canadians who guided us through the first years of the pandemic—public health leaders, epidemiologists—have given way in this year’s ranking to those who will guide us out of it.

It’s our version of cautious optimism. With luck and good sense, we’ll emerge from Omicron into a world where COVID-19 is a managed risk, refocused on the challenges that define Canada and its place in the world. As ever, our ability to navigate these challenges will rest heavily on our brightest, most dauntless and most accomplished. Remember their names, and lend them your ears.