Remembering Bromley Armstrong, and the segregation of Canada’s stories

Opinion: Bromley Armstrong—who passed away on Aug. 17—helped end the segregation of Canada’s public spaces. Why don’t more Canadians know his name?

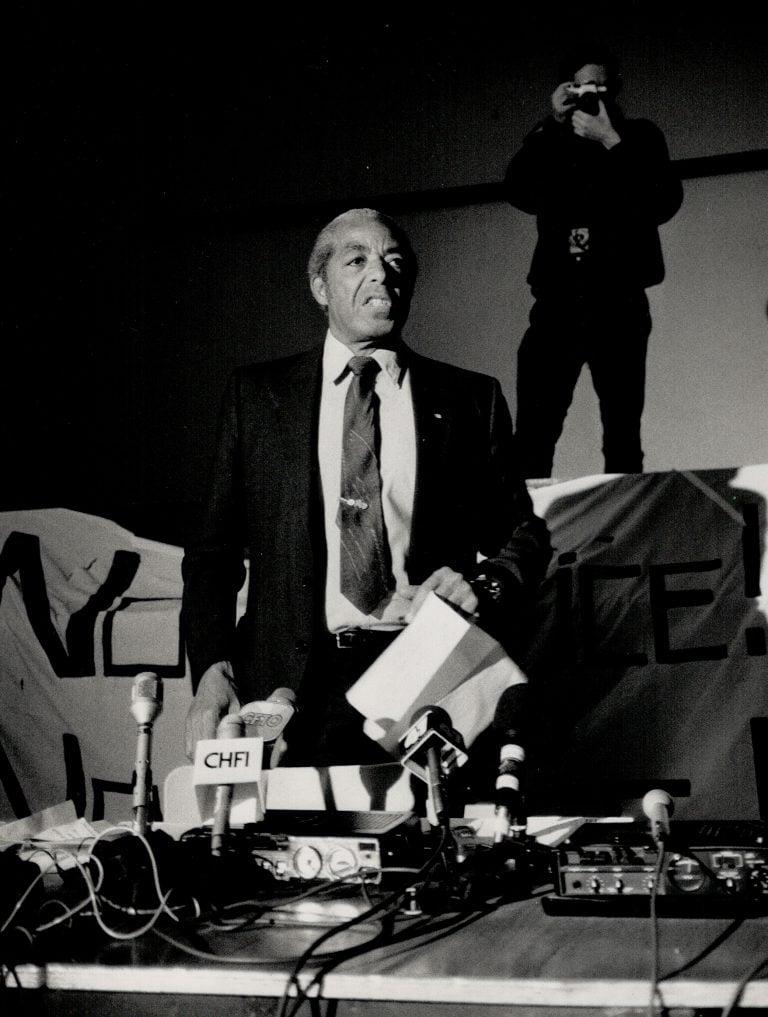

Bromley Armstrong, in a photo dated 1989. (Dale Brazao/Toronto Star via Getty Images)

Share

In January of 1991, when I was in the fifth grade, my mother woke me up early on a Saturday morning to go to school. I put on a white dress shirt, navy blue pants, and a matching tie before she packed me into the car and drove me across town to Higher Marks, a tutoring and mentorship program for Black youth in the Greater Toronto Area. At the time, the school was located near the intersection of Bathurst and Bloor streets, a corner that functioned as one of Toronto’s original Black business hubs and community gathering spots. While my friends ate sugary cereals and gorged themselves on morning cartoons, my mother parked my behind in a cold, cramped classroom to learn advanced math skills and Black Canadian history.

I hated it, of course. But it was in Dr. Ronald Blake’s classroom at Higher Marks that I first learned the phrase “Jim Crow,” and that even in Canada, the fight to end segregation was long and arduous. There were no textbooks we could flip open to read this history, and Google wasn’t yet even a twinkle in Larry Page and Sergey Brin’s eyes. It was inside that classroom that I learned of our separate history, carried on the lips of Black community members who were either born or immigrated to this country early enough to have witnessed the events as they happened.

This is one of the stories I first learned at Higher Marks.

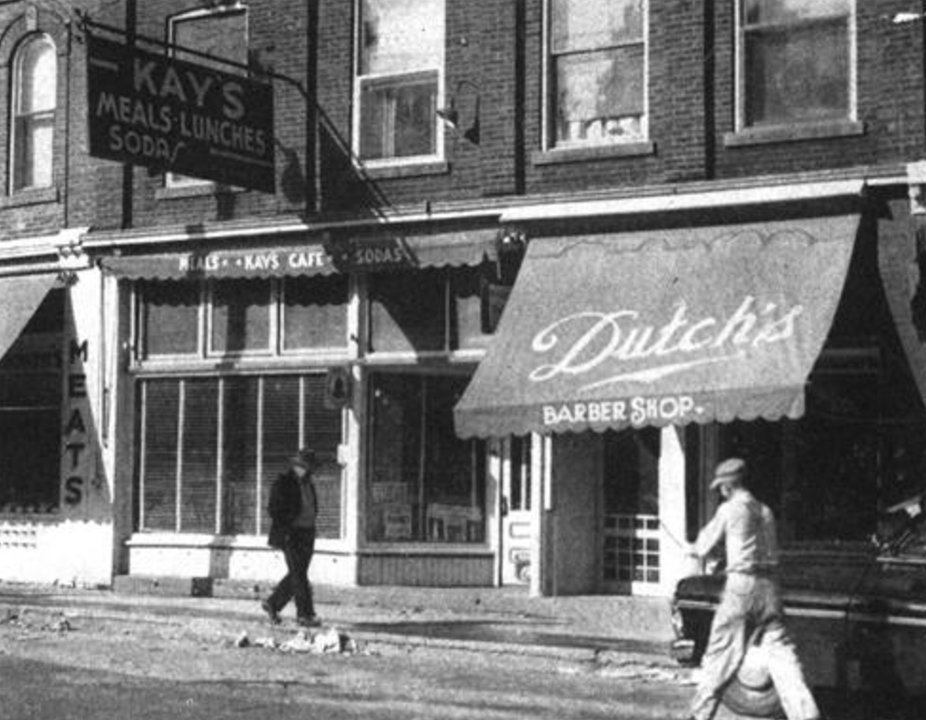

In July of 1943, carpenter and Second World War veteran Hugh Burnett wrote a letter to federal justice minister Louis St. Laurent about an incident he felt demanded the minister’s attention. While Burnett was in town to visit relatives, he went to have lunch at Kay’s Café, a restaurant in Dresden, Ont., while wearing his army uniform—the one he voluntarily put on to fight the tyranny of the Third Reich. But because he, like approximately one-fifth of Dresden’s 1,700 residents, was descended from slaves who escaped to freedom via the Underground Railroad, he was told he was not welcome to eat at that counter. Its proprietor, Morley McKay, was a flagrant racist who, like many of Dresden’s white residents, believed in the separation of the races.

St. Laurent’s reply to Burnett’s letter was curt and dismissive: there was no law in Canada that barred racial discrimination.

In response, Burnett, his family, and several Dresden residents organized over several years to form the National Unity Association, which joined with the Toronto-area Association of Civil Liberties to draw attention to Dresden’s Jim Crow-like racial atmosphere. Vivien Mahood, chair of the ACL’s committee on group relations, contacted Maclean’s managing editor Pierre Berton in 1949 regarding the town’s growing discontent, and Berton dispatched feature writer Sidney Katz to cover the story. Katz’s article, “Jim Crow Lives In Dresden,” helped propel the Dresden story to national interest, even quoting McKay as saying “I get raging mad every time 1 see a Negro. Maybe it’s like an animal who’s had a smell of blood.”

The story of Dresden helped precipitate two events in 1954. One was a 30-minute documentary entitled Dresden Story, in which residents debated the problem of segregation, and in which pro-integrationists were even accused of having “communistic influences;” it was an eye-opening look at the intellectual lengths to which white Canadians would leap in order to keep Black Canadians yoked to second-class citizenship. The second was the Fair Accommodation Practices Act, passed into law by Ontario premier Leslie Frost, a Progressive Conservative who served at a time when the party stood for racial and gender equality. The act erased the ambiguity of anti-discrimination policies that varied from municipality to municipality, and made clear the province’s stand on segregation: “No person shall deny to any person or class of persons the accommodation, services or facilities available in any place to which the public is customarily admitted because of the race, creed, colour, nationality, ancestry or place of origin of such person or class of persons.”

In order for the law to be effective, though, it had to be enforced. And in order for that to happen, businesses had to be caught in the act of discrimination. Enter a 21-year-old labour activist named Bromley Armstrong.

Along with University of Toronto student Ruth Lor, Armstrong was dispatched to Dresden in the fall of 1954 to sit at Kay’s Café and request service. According to Armstrong, McKay became so angered at this “test” that Armstrong feared that the man would attack him with the meat cleaver he was holding. The cafe’s waitress refused them service, which not only violated the law but also exposed McKay in front of undercover reporters that were invited from Toronto to witness the test. McKay was prosecuted by the government of Ontario, marking a first for Canada: a racial discrimination trial in which a business establishment was the defendant.

McKay would go on to lose the trial, successfully appeal on the basis that a business proprietor shouldn’t be punished for the actions of an employee (i.e. the waitress who refused service), and then lose on the basis of another test, in which his overconfidence in the secret handshake of white supremacy led both the waitress and himself to deny service to two more Black patrons.

Armstrong’s name would become widely known throughout the Black Canadian community over the course of his decades-long career in civil rights and labour activism. He helped to found the Jamaican Canadian Association, the Black Business and Professionals Association (with which I’ve served as a board member and consultant), the Black Action Defense Committee (which successfully pressured Ontario into create the Special Investigations Unit oversight branch, for police incidents involving injury, death, and sexual assault of civilians), and the Urban Alliance on Race Relations.

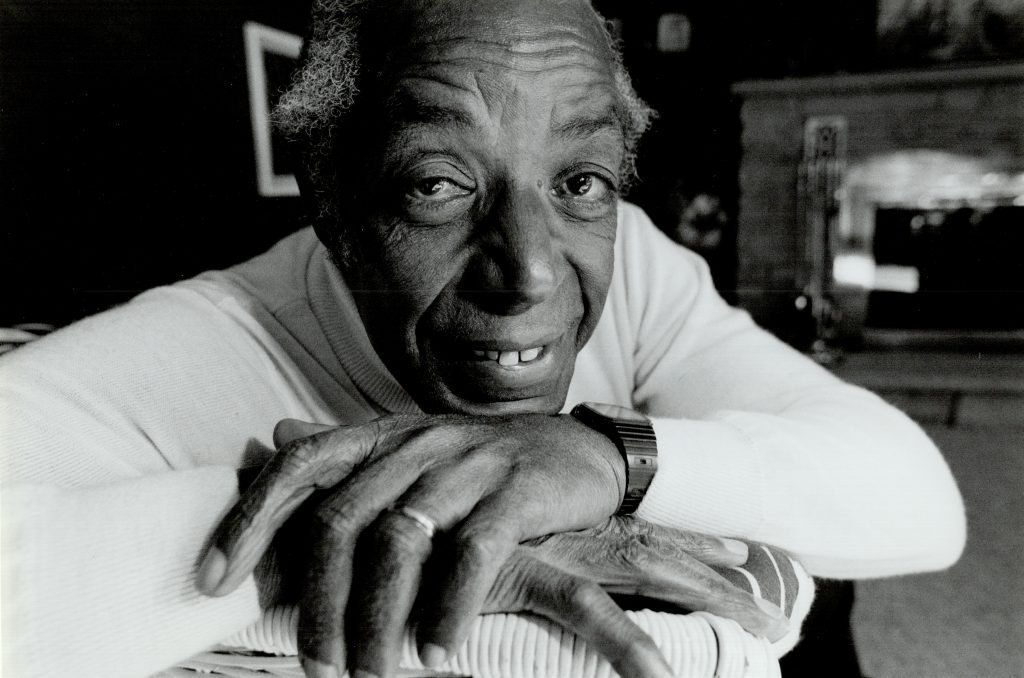

For his tireless work, Armstrong was granted a seat on the Ontario Human Rights Commission, as well as admission to the Order of Ontario, and the Order of Canada. And after a life lived in service to the communities he loved, Bromley Armstrong passed away on Aug. 17, at the age of 92.

And yet, outside of labour websites and Facebook tributes from small-press Black publications in Toronto like Share Magazine and Pride News, media coverage of his death was nonexistent. While activists like Bromley Armstrong helped end the segregation of Canada’s public spaces, his story has been deeply segregated from public knowledge.

By Aug. 22, Black journalists (including myself) began to make noise on social media, arguing that it was unacceptable that the passing of someone with such a rich legacy, and whose work helped drag Canada into civil-rights modernity, would go unremarked upon by the mainstream media. It wasn’t until a week after his death, on Aug. 24, that CBC’s “As It Happens” picked up the story—and even then, in the original published draft, Armstrong was incorrectly reported to have died the previous Saturday.

Bromley Armstrong’s life, and his work, matters. Within the Black community, this is incontrovertible fact. But in our classrooms, almost 30 years after I first set foot in Higher Marks, his name is still absent from the textbooks. And in our newsrooms, where Black journalists regularly watch our colleagues take cameras and laptops out to our neighbourhoods to report tragedies in our community, and convert our blood into copy, clicks, and revenue, our history might as well be that of some small, unremarkable country overseas.

I attended Armstrong’s wake, and shook hands with his family. There were labour activists present, a few MPs and MPPs, and members of the organizations that Armstrong helped found. It was not a somber event, but a joyful one, as people shared stories about the man, including that long-ago time when he sat stoically at a café table while a bigot, armed with a meat cleaver, hurled insults his way. And it saddened me to know that, if it hadn’t been for the few Black journalists in Canada’s media industry holding their colleagues’ feet to the fire, some of the people listening to those stories might not have known who the man was.

And if it wasn’t for Higher Marks, I might not have known either. None of what I learned in Dr. Blake’s classes—not in middle school, high school, or university—was any of this history taught. As with most Black Canadian history—the razing of Africville, the No. 2 Construction Battalion, the trial of Viola Desmond, and stories of Armstrong, Burnett, Lor, Joseph Hanson, Bernard Carter, Lyle Talbot, Sid Blum, and the National Unity Association—there was no space in the public school classroom for the Dresden sit-ins. Instead, during the school week, my classmates and I read books about Sir John A. Macdonald and the formation of the Dominion. But on Saturdays, in a classroom my mother worked double shifts for me to attend, I watched a VHS copy of Dresden Story. I read news clippings blurred by the imperfect cloning process of the photocopier, as well as Katz’s story. And I listened to an instructor who knew Bromley Armstrong on a first-name basis—as well as several other Black civil rights activists, like Charles Roach, Dudley Laws, and Denham Jolly—deliver the man’s oral history. Otherwise, I might never have known about the Dresden story at all.

As the concept of diversity comes under attack by white nationalists in Canada, and when prominent members of Canada’s opposition party have castigated the taking-down of Macdonald statues as the erasure of history, it’s time for this whitewashing of our history and of the quiet struggles that people of colour have undertaken to end. Slowly and inevitably, the civil-rights generation is leaving us behind in troubled times. The story of Dresden led to the end of segregation, and if that can teach us anything, it’s this: if we truly want unity and shared values to prevail in Canada, some stories have to be told.