The Reformation at 500: Grappling with Martin Luther’s anti-Semitic legacy

Opinion: On the Reformation’s 500th anniversary, what lessons have been learned from the virulent but influential hatred of a foundational church figure?

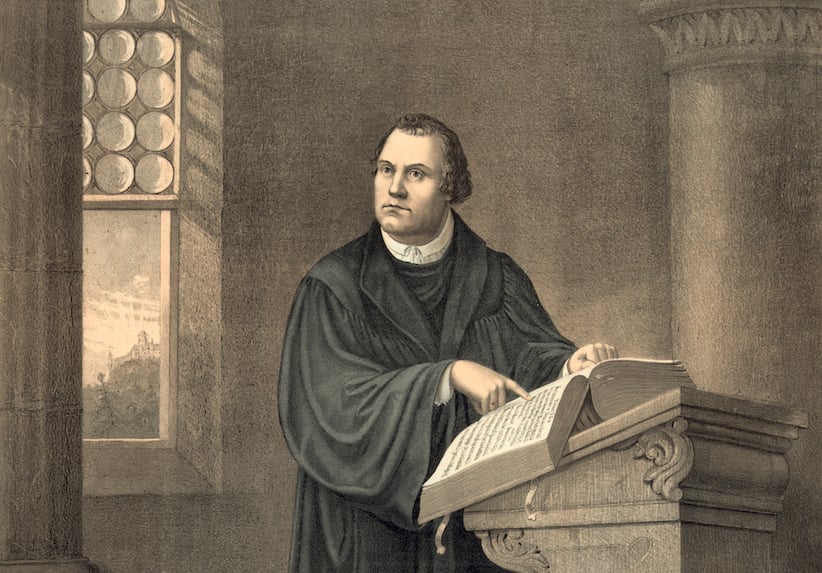

Antique print of Martin Luther in his study at Wartburg Castle in Eisenach (lithograph), 1882. (Photo by GraphicaArtis/Getty Images)

Share

Michael Coren is a journalist and broadcaster and the author of 16 books.

It’s party time in the religious world. On Oct. 31, Christians—or, to be more precise, Protestant Christians, with a surprising amount of support from the Vatican—celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, when legend has it that German monk and professor Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses on the door of the castle church in Wittenberg, thus lighting the fuse that blew European Christendom apart.

It matters far more than one might think, because it was not only religion but politics, culture, and economics that would change in that hammering’s wake. In the document, Luther made public his condemnation of the sale of indulgences—money paid to reduce the time spent in purgatory, a sort of waiting room before heaven, by relatives and loves ones. But this academic disputation went further than that, and it was a manifesto of criticism aimed at Roman Catholicism. History, as it were, was given a reboot.

There is much that is positive about Luther. He liberated people from rigid church control, gave impeccable energy to the idea of the individual’s relationship with God, and worked to eliminate corruption and superstition. In many ways, he was a pioneer not just of religious change, but of modernity.

But behind his undeniable genius was a gritty nastiness. He could be crude, abusive, angry, and, perhaps most tragically, profoundly anti-Semitic—a legacy that needs to be grappled with, even 500 years later.

He started as a supporter of the Jewish people, arguing quite rightly that they had been badly treated by the Roman Catholic Church, and quite wrongly that they, if presented with what he regarded as a more authentic Christianity, would surely convert. In 1523 he wrote an essay, entitled “That Jesus Was Born a Jew,” condemning the fact that the church had “dealt with the Jews as if they were dogs rather than human beings; they have done little else than deride them and seize their property.”

But the Jews did not convert, and Luther reacted appallingly. In 1543, he published “The Jews and Their Lies,” which today is shocking in its venom, and even for its time stood out as particularly cruel and intolerant. In the 65,000-word treatise, he calls for a litany of horrors, including the destruction of synagogues, Jewish schools and homes; for rabbis to be forbidden to preach; for the stripping of legal protection of Jews on highways; for the confiscation of their money. The Jews are, wrote Luther, a “base, whoring people, that is, no people of God, and their boast of lineage, circumcision, and law must be accounted as filth.”

Some of his defenders have claimed that Luther was old and ill when he wrote this, ignoring the fact that he lived another three years after the essay and that most of us become mildly grumpy when we feel unwell, not genocidal. Plus, Luther had also managed to have the Jews expelled from Saxony and some German towns as early as 1537.

And regardless of his intentions, Luther’s thinking on the Jewish people had a direct impact on history: The Nazis amplified Luther’s anti-Semitism from the earliest days of the National Socialist movement. It helped in the creation of the heavily Nazified and racist faction of Deutsche Christen, or German Christians, within the German Lutheran church, but perhaps more significantly, partly enabled the culture of anti-Semitism that made the Holocaust possible.

One especially repugnant case is that of Martin Sasse, the Bishop of the Evangelical Church of Thuringia during Kristallnacht in 1938. He feted the pogroms and the mass destruction of synagogues and Jewish businesses, and even tied it explicitly to Luther himself; just days after what was in effect the beginning of the organized slaughter of the Jews, he distributed a pamphlet entitled Martin Luther on the Jews: Away with Them! in which he claimed the Nazis were acting as Christians in their violent anti-Semitism, and that this was precisely what Luther would have wanted.

Yes, there was also a powerful anti-Nazi movement within Lutheranism, and the sacrifice and even martyrdom of those pastors and laypeople must never be forgotten. The Confessing Church, for example, was formed in opposition to the regime’s attempt to unify all German Protestants into a single pro-Nazi church. Leaders like Martin Niemoller and Heinrich Gruber were sent to concentration camps but survived; writer and activist Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who was accused of being part of a plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler, did not.

But Luther was not unique in his Christian anti-Semitism. It’s such a grotesquely paradoxical reaction, of course; Jesus and most of the founders of Christianity were Jewish, but many of those claiming to love Him have hated His race and people. St. John Chrysostom, a major influence on the Eastern Orthodox Church, was virulently anti-Semitic; in 1555, Pope Paul IV issued a bull removing the rights of the Jews and subjecting them to communal humiliation. The examples are, alas, legion. Christians deliberately expunged the Jewishness of their faith and thus distorted it and shamed the teachings and life of that 1st-century Jewish preacher from Galilee. It’s a birth defect of the historic church, and it didn’t take very long for early Christian leaders to join the club—and while Luther did not codify his hatreds into tangible church policy, he left a heritage of antagonism and hostility all the same.

But 500 years later, have lessons been learned and wounds healed? Is the world a better and kinder place now because Christians have realized their colossal failures, stemming from one part of the church’s founding figures? It’s a layered answer. The Roman Catholic Church formally rejected its doctrinal anti-Semitism at the Second Vatican Council in 1965, and Catholics have worked diligently and genuinely to build bridges with the Jewish world since then. And outside of fringe conservative movements within the church, Rome has been largely successful. Protestantism is diverse by its very nature. Evangelical conservative Christians frequently adopt a Christian Zionist stance and are passionate supporters of Israel, even if often for mangled reasons; the underlying theology looks to the world’s Jews moving to Israel en masse, thus hastening the second coming and the end times. Lots of fire and mayhem to come—sinners beware.

Liberal Protestantism, including most Lutherans, is less absolute. In 1994, the 5-million-member Evangelical Lutheran Church in America spoke publicly of Luther’s “anti-Judaic diatribes” and denounced “the violent recommendations of his later writings against the Jews.” The Central Council of Jews in Germany had long asked for a formal statement from Lutherans on the subject of anti-Semitism, and just last year, the Lutheran Church in Germany obliged, condemning Luther’s writings on the Jews and “the part played by the Reformation tradition in the painful history between Christians and Jews.” The state Lutheran churches in Norway and the Netherlands have followed suit.

Other Lutheran churches reacted earlier; the American Lutheran Church, for instance, acknowledged it as early as 1974. In 1998, on the 60th anniversary of Kristallnacht, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria issued a declaration that “it is imperative for the Lutheran Church, which knows itself to be indebted to the work and tradition of Martin Luther, to take seriously also his anti-Jewish utterances, to acknowledge their theological function, and to reflect on their consequences. It has to distance itself from anti-Judaism in Lutheran theology.”

The situation is confused by the situation in the Middle East. Progressive churches have been some of the first to admit and condemn past anti-Semitism, but have been equally bold in criticizing Israel, sometimes stridently. Informed critiques of certain Israeli policies is certainly not the same as anti-Semitism, in spite of what some zealots might have us believe, but there are times when attacks on Israel by Lutherans, the United Church and other liberal Protestants do seem to lack historical context and sensitivity to the Jewish experience, and seem more angry at the Jewish state than committed to a greater social and international justice. There have, for example, been numerous motions and even decisions to boycott and disinvest from Israel while at the same time brutal Muslim theocracies have been largely ignored.

Put simply, one of the prime reasons for the creation of Israel in 1948 was because European Christians had acted against their faith and persecuted the Jewish people. It’s imperative that Christians understand that, but it’s unclear that enough of them do. But for all that, the twin solitudes of Jews and Christians were broken down long ago. William Temple, for example, became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1944 and helped co-found the Council of Christians and Jews; in 1943, he spoke out in the House of Lords about the Nazi persecution of the Jews, insisting that, “We at this moment have upon us a tremendous responsibility. We stand at the bar of history, of humanity and of God.” That type of stance has been replicated and applauded myriad times since then and now, thank God, flows through the bloodstream of contemporary denominations. When in 2008 Lord Jonathan Sacks, the chief rabbi of the Commonwealth, publicly referred to the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Archbishop of York as “beloved colleagues,” he meant it. When in 1986 John Paul II entered Rome’s Great Synagogue, the first Pope since St. Peter to enter a Jewish place of worship, the emotion was genuine.

As a Christian with three Jewish grandparents, I have hardly ever experienced any anti-Semitism in the church. But as I celebrate this 500th anniversary, I will do so with reservations. Not because I regret the Reformation—far from it—but because the otherwise sparkling lens that Luther provided is not, for me and I know for many others, completely clear. And that’s so terribly sad.

MORE ABOUT RELIGION:

- Why Quebec’s Bill 62 is an indefensible mess

- Jagmeet Singh’s Quebec problem

- Q&A: Reza Aslan on religion and U.S. politics

- Atheist United Church minister to start new secular community

- Nine interesting data points on the state of today’s Protestant churches

- It has risen: Is this the key to growing Protestant churches?

- Praise the Lord and grab the money

- Did Jesus really exist?