‘We had good intentions but we fell short’: What it means to be a baby boomer

Don Gillmor: We strived for a better world. And then we grew up. And now, politically, the world looks like the episode of ‘The Simpsons’ where the dim-witted Homer blows up Springfield.

Don Gillmor in his home office (Photograph by May Truong)

Share

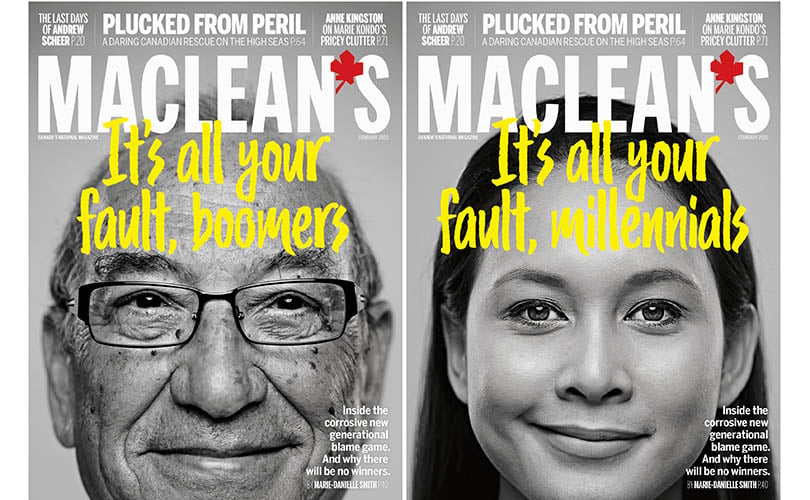

This essay is from the February 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine, which charts the current conflict between boomers and millennials—one of the defining struggles of our age. The issue has two different covers. Here’s why.

In high school I marched for nuclear disarmament because I had a crush on a girl who was marching. We carried banners and chanted something uplifting. Afterwards, we went to a coffee house (yet to be called “cafés”), listened to Leonard Cohen songs and basked in our activism.

It was 1969 and John Lennon and Yoko Ono were staging a bed-in for peace at Montreal’s Queen Elizabeth Hotel. Later that year they met with our hip Prime Minister, Pierre Trudeau, to discuss disarmament. As it turned out, the bed-in and our anti-nuclear march—one of hundreds—didn’t do the trick. Over the next 16 years, the world’s nuclear arsenal increased from 38,000 weapons to more than 61,000. That stockpile has since been reduced, but the 14,000 weapons still out there aren’t a comfort. This will be a part of our legacy—we had good intentions and infectious energy, but ultimately, we fell short.

For many boomers, the ’60s remain the defining decade; all that music, all that change, “free love,” bad fashion, long hair and marches. It was like Camelot with a backbeat. But there are boomers and there are boomers. Because of the size of our cohort (born between 1946 and 1964), there are boomers who came of age in the 1980s, more or less the opposite of the 1960s. Idealism had been edged out by consumption by then. The Age of Aquarius become the Age of Mutual Funds.

COVER STORY: Inside the corrosive new generational blame game

I grew up between these two poles, but we were all joined by the idea of youth. We felt that we created the concept, and to some extent, we did. Certainly, no generation held onto it for as long—50 years in some cases—or was so reluctant to give it up to the next group. We changed music and fashion but failed to have much impact on politics, despite the marches, slogans and campaigning. We championed the environment, but now find ourselves in this Old Testament mess. We denounced racism and find it hasn’t changed much in 50 years. I raised my fist at rock concerts when skinny, drug-assisted singers denounced hatred or violence or The Man or whatever. But time rolled along. The rich got richer and the world got more dangerous.

There were moments when we pulled together in those exhilarating numbers, but over the decades we drifted apart. One of the greatest misunderstandings of my generation is that we are a monolithic force. The boomers are more like the country itself, bound by different languages and separate interests, histories and fears.

Rebellion is the prerogative of youth, and our first rebellions happened in the nation’s homes, arguments over hair and politics and whether Grand Funk Railroad was a great band (the parents were right about that one). I saw this in the homes of my friends, though there wasn’t much to rebel against in my own home. My parents were young and progressive, and my mother would have preferred my hair to be longer than it was. The church we went to featured Simon and Garfunkel songs, but even that wasn’t enough to keep us in the fold. Like so many others, we drifted away from Jesus.

ANNE KINGSTON: Why intergenerational warfare is a mug’s game

Boomers tore down institutions—divorce rates went up, churchgoing went down. We demonized the corporations that previous generations had venerated, though we bought their products in record numbers, our idealism blurring with the search for the perfect pair of jeans. We wanted it all. In place of institutions, we created the cult of the individual, our own particular Frankenstein.

Music was such an important element in those days. It was the most dramatic separation from the previous generation: The soundtracks of our early lives were the Beatles and the Stones; Frank Sinatra was replaced by Led Zeppelin. Now I hear Zeppelin’s “Rock and Roll” in Cadillac commercials. The Beatles have been used to promote Nike running shoes (“Revolution”) and banks (“All You Need is Love”). The Stones’ “Satisfaction” was used in a Snickers ad, and “Brown Sugar” was used by Pepsi, which was, at least, truth in advertising.

So much of our music comes back to us in unfortunate ways, Dylan’s anthems barely recognizable in sappy orchestral arrangements that fill the hours we spend on hold. And we seem to be permanently on hold these days. We are between 55 and 73 years old now, still defining this as middle age, still a potent economic force because of our numbers, controlling 70 per cent of disposable income, though it feels to many of us that we have already disposed of it. Still, we bought houses when they were vaguely affordable. And politicians still cater to us because we vote en masse. However, we are largely left out of the cultural conversation, as music and social media continues to evolve, always leaving us one app behind the curve.

MORE ESSAYS:

‘Self-sufficient and unassuming’: What it means to be Gen X

‘Directionless and lost’: What it means to be a millennial

‘Don’t you see yourself in us?’: What it means to be Gen Z

We rejected the generations that came before us and were too self-obsessed to notice the generations that came after us. We notice them now, now that we find ourselves increasingly baffled by technology, edged out of the workplace by those who grew up with it. And our criticism of them is eerily similar to what our own parents were saying to us 50 years ago—you’re entitled, naïve, and your music sucks.

We strived for a better world—freer, more egalitarian, more peaceful. Some of this change stuck (thank you, sexual revolution). Then we grew up and faced the mortgages, financial worries and health woes that every generation does. The pot dealers became real estate agents or premiers. And the world we helped create is now worrisomely inegalitarian and self-destructive. Politically, it looks like the episode of The Simpsons where the dim-witted Homer blows up Springfield. But there was a moment when there was genuine passion and a sense of community that hadn’t been co-opted by the virtual world. Every generation falls short of its ideals, but the ones we had were laudable.

Last September, I went to see The Who at Toronto’s Scotiabank Arena, a sold-out sea of grey, pony-tailed men. Pete Townshend, 74, and Roger Daltrey, 75, were in fine form, backed by members of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. They rocked out. Technically, neither are boomers. They are arguably the two loudest members of what has been labelled “The Silent Generation,” born before 1946. Noticeably absent from the set list was the anthem “My Generation” with its iconic ’60s lyric, “hope I die before I get old.”

This essay appears in print in the February 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “The music of our youth.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.