With his antics, the B.C. Greens’ Andrew Weaver risks making himself irrelevant

Opinion: The most powerful non-premier in B.C. has been prone to outbursts in his time as the province’s kingmaker—a reminder of the risks of outsider politics

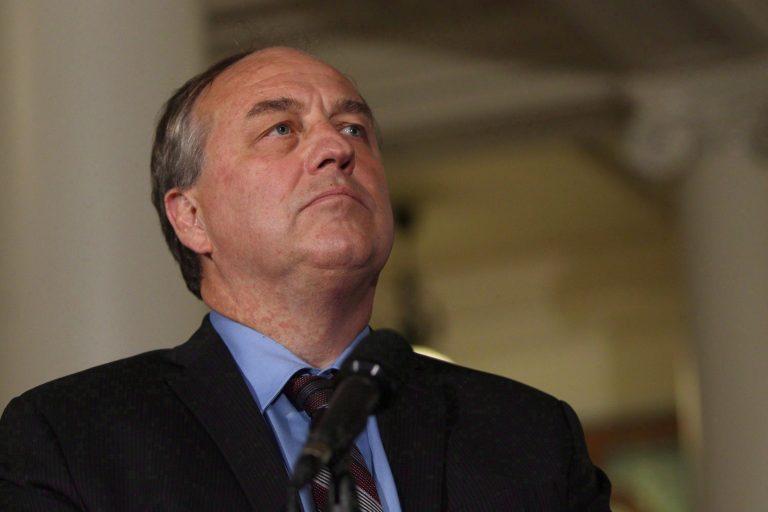

B.C. Green party leader Andrew Weaver speaks to media at the legislature in Victoria, B.C., on Tuesday, May 30, 2017. (Chad Hipolito/CP)

Share

If you had wagered in the early spring of 2017 that British Columbia Green Party leader Andrew Weaver would be one of the most powerful residents of the province just months later, you’d have met long odds and won a fortune. You might’ve even won enough to buy a house in Vancouver. After all, who could have predicted a hung legislature in which the third party would hold the balance of power?

History suggests that British Columbians prefer the makeup of their legislatures, if not their politicians, to be predictable. Indeed, prior to last year, there hadn’t been a minority government in B.C. since 1952. At the outset of the 2017 election, as close as the race seemed, the Liberals had a good chance at maintaining the status quo: they had governed with majorities since 2001, enjoyed a favourable economy, and were helmed by one of the most tenacious retail politicians in the country.

Life and politics being what they are, however, the usual happens until it doesn’t. British Columbians awoke May 10 to razor-thin margins in the legislature: the Liberals with the most seats—43 of 87—but not enough to govern without support, opposite 41 New Democrats and three Green Party MLAs, which tripled the party’s strength from the previous contest in 2013. The Liberals had won the most seats and the most votes, dropping only a few percentage points off their 2013 win, but a quirky first-past-the-post electoral system proved fickle. Suddenly, Andrew Weaver—leader of his party since December 2015, scientist, professor, and a not-a-politician politician—was also the head of a caucus that would play kingmaker in the province. Weeks later, after frenetic negotiations between the Greens and their suitors, the party backed the NDP, and now John Horgan’s party governs with the support of the Greens under their supply and confidence agreement (known as CASA), relying on them to pass legislation, maintain confidence, and remain in power.

But in a province that is used to stable majority governments, Weaver himself hasn’t done much to assuage a skittish electorate with his occasionally mercurial disposition and his recent outbursts.

Last month, the Green leader held a strange, rambling press conference that ran nearly half an hour after Horgan announced measures to support the liquefied natural gas industry in the province, including generous tax breaks. Weaver railed against the NDP government, suggesting that their LNG plan violated CASA, and threatened emissions targets—and possibly the confidence of the third party. Nonetheless, after some bluster, Weaver concluded that he’d wait to see the LNG legislation before he decides whether to bring down the government at the next opportunity. His approach seems pragmatic enough on the face of it, though it leaves some room for uncertainty. In January, the Green leader tweeted, “Lest there be any doubt, let me be perfectly clear: NDP government will fall in non confidence if after all that has happened it continues to pursue LNG folly.” It was neither his first nor his last outburst on social media; there were so many, in fact, that during the election, an enterprising Twitter user captured screenshots of Weaver’s Twitter brouhahas and set them to the Gary Wright song “Dreamweaver.”

READ MORE: B.C.’s housing debate is political. A foreign investment ban is politics.

Then, just weeks ago, Weaver was at it again, losing his temper after a procedural error—arriving late—cost him his chance to speak to several sections of a bill that subsequently passed. “Let’s have an election,” he said—and thus also quasi-threatened—directing his ire at the opposition Liberals whom he blamed for his missing his moment. Cannon to the left of him, cannon to the right.

Last year, a big part of Weaver and his party’s charm was that they were different. Many in the province were tired of the Liberals, but plenty of those voters had little interest in supporting the NDP. Meanwhile, disgruntled New Democrats were loath to support Clark and her blue-red team. The Greens were considered a principled third option with room to grow—a protest-plus choice. Before the election, the party announced they wouldn’t accept union or corporate donations while the others continued to do so. They ran on bringing citizens into the process. On aggressively protecting the environment. On affordable homes and child care. On better transit. After an inspired campaign, they more than doubled their popular vote from 8 to 17 per cent and tripled their seats from one to three. But Weaver’s success made him the dog-that-caught-the-car: now that he’s nabbed the fender, what the hell does he do now?

The affable, intelligent, Pokémon-Go-playing-in-the-legislature, goofy-dad professor—charismatic in his way, someone with whom I’d definitely have a coffee and a long chat, if only to listen—Weaver is a case study in what happens when the “I’m not a politician” politician suddenly finds himself influential.

READ MORE: B.C.’s carbon-tax changes are covered in Green thumbprints

Criticisms of politics often turn on disliking inauthenticity, choreography, and business as usual, which is why, from time to time, outsiders enjoy success when they buck the trend and promise to do things differently. But while slavish devotion to the carefully managed status quo ends up turning in on itself and becomes regressive, the characteristics of politics that make it seem like theatre—in which all players and the stage are carefully managed—do exist for a reason. Sometimes, what seems to be phony, planned, and predictable boilerplate is an attempt to keep the institutions that make political, economic, and social life scrutable and manageable.

So when the outsider wins or becomes unexpectedly influential, when he or she arrives to “shake things up,” we often find that what we get is less a sure bet (“We know what we want, we just need someone who’ll come in and do it!”) and more a throwing of the dice (“Come on, daddy needs a new mass transit system!”). Or, to be plain: things get risky and unpredictable.

There’s opportunity in risk. A lot of good can come from a risky environment: a lot of change, a lot of new thinking, a lot of the outside getting inside. The NDP government, supported by Weaver and the Greens, has already started to transform politics in the province, focusing on affordability over the provincial credit rating, recognizing that economic growth is meaningless on its own, even counterproductive unless the fruits of our collective labours are equitably, if not equally, shared. But what if Weaver makes good one day on his semi-regular threats to bring down the government? What if his intransigence on one issue or another undermines the careful balance that needs to be struck when governing a diverse province marked by persistent disagreement and incompatible interests? What if voters just plain get sick of his antics?

It’s early days for Weaver and his Greens. It could very well be that in the weeks and months to come, the third party chief levels out a bit and finds a balance between the politics of outrage and the outrage of politics, striking the right balance between his need to oppose the government (as the leader of an opposition party) and support them (as a CASA-bound supporter in the legislature). That would be ideal. The alternative is a series of ongoing, perhaps escalating, threats that will culminate in what my grandfather would call a “piss-or-get-off-the-pot moment”: if you’re going to issue threats and ultimatums, you’ll eventually have to make good on them or else you’ll quickly reach a point at which you’re no longer taken seriously. And in politics, not being taken seriously is the last stop before retirement or, worse, irrelevance.