338Canada: Why the CAQ now dominates Quebec

Philippe J. Fournier: While the Liberals and Conservatives are all over the map, Legault’s coalition has found the optimal recipe for current Quebec politics

Legault walks to Question Period with members of his staff as the legislature resumes for its spring session on Feb. 2, 2021 in Quebec City (CP/Jacques Boissinot)

Share

In the 2018 Quebec general election, François Legault’s CAQ broke a political cycle that had lasted almost a half century, during which the Quebec Liberals and Parti Québécois took turns at the reins of the National Assembly. With the Quebec national question getting relegated to the back burner for many slivers of the Quebec electorate—most notably young voters and aging baby boomers—both the Liberals and PQ lost what had been their campaigning bread and butter for the past 50 years: Canadian unity versus Quebec independence. François Legault offered a third option: The economy, education, and a nationalist “Quebec First” attitude with all aspects of governing the province.

It worked. Not only has the CAQ won a 74-seat majority in that election, the allure of the CAQ’s middle way has nothing but increased since then. As mentioned in last week’s column, the CAQ is leading voting intentions in Quebec with the support of almost half of Quebec voters, including a crushing 40-point lead among francophones. According to the 338Canada Quebec model, the CAQ would easily surpass its 2018 score (with 90 seats on average) and leave opposition parties in the dust.

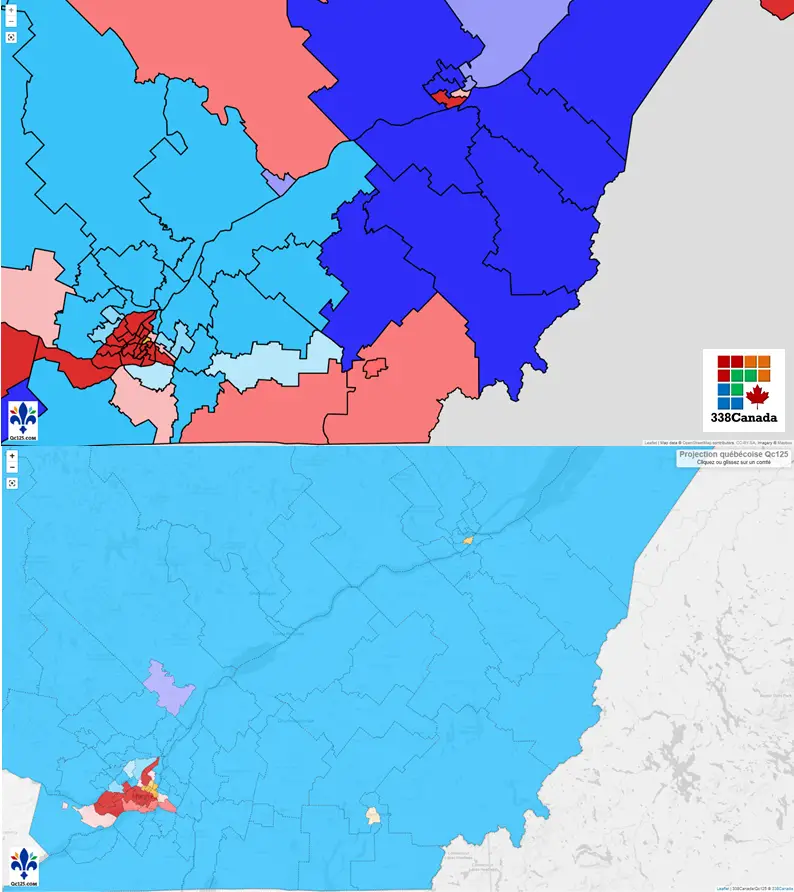

There are several complex and historical explanations for the current success of the CAQ, but let us apply Occam’s principle of parsimony here: The “C” in CAQ stands for “Coalition”. This simple fact could hardly be more obvious when comparing the current provincial and federal projection maps of Quebec. The top half of the figure below is the federal projection of southern Quebec: Red for LPC, blue for CPC and powder blue for the Bloc Québécois; the bottom half is the provincial projection: specks of red (QLP) and orange (Québec solidaire) are lost in a sea of powder blue (CAQ) that spans all of the Montreal suburbs, the Eastern Townships, and all ridings along highways 20 and 40 towards Quebec City:

As the federal Liberals, Conservatives and Bloc Québécois are all projected to win chunks of the Quebec map, the CAQ plows through all regions of southern Quebec except for the island of Montreal.

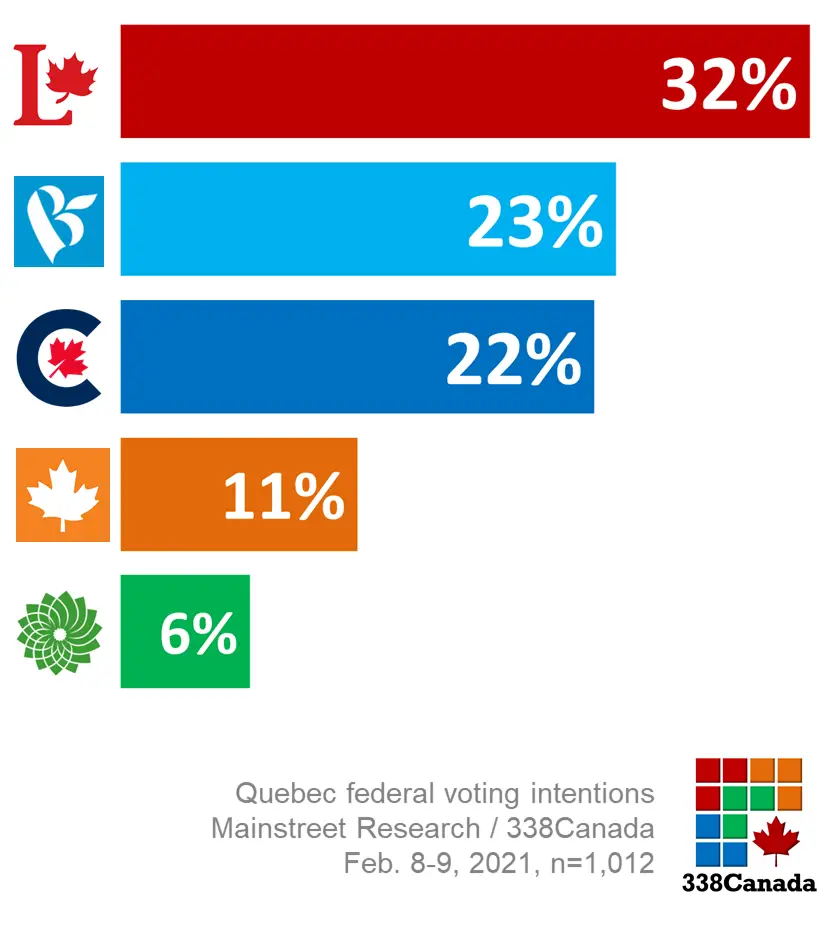

Let us add fresh polling numbers to this analysis. We present today the second part of Mainstreet Research’s Quebec poll, which includes crosstabs of federal party support with provincial voting intentions.

Among all respondents of the poll, the Liberals lead the fray with 32 per cent. The Bloc Québécois and the Conservatives are in a statistical tie for second place with 23 and 22 per cent respectively:

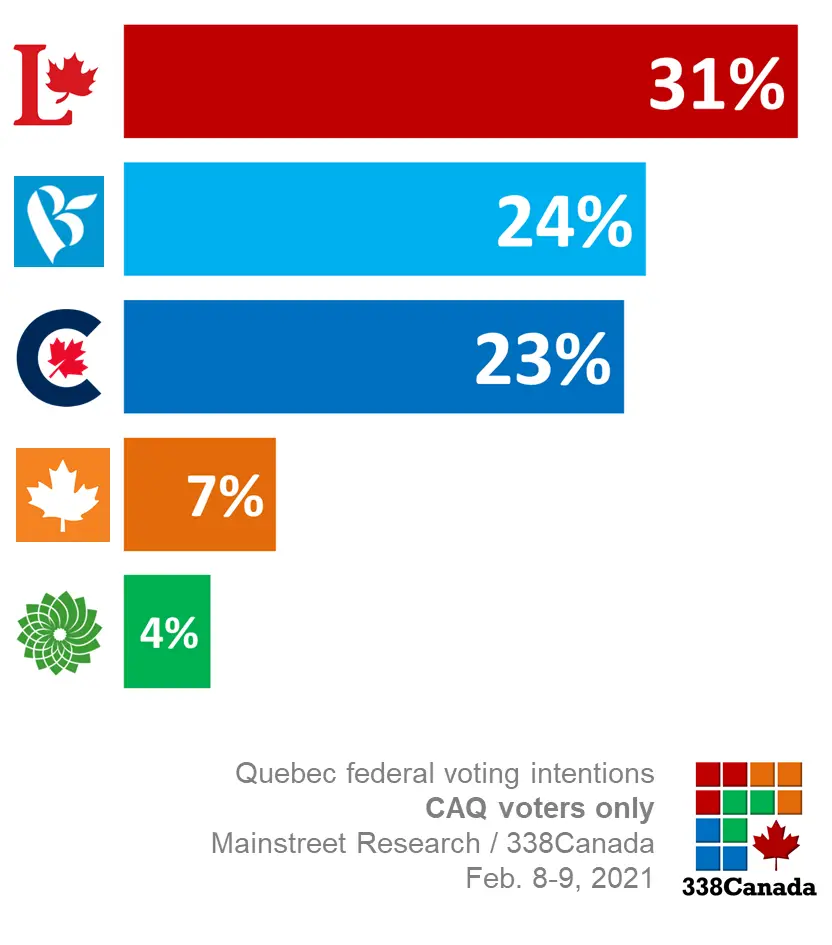

When we isolate results of federal voting intentions by provincial voting intentions, we can clearly see the “coalition” that makes up the core of CAQ supporters. Unlike the QLP and the PQ, two parties that have natural cousins at the federal level in the LPC and BQ, CAQ voters are a little all over the map:

Among CAQ voters only, the federal Liberals receive the highest share of support, but it is nowhere close to a domination: The LPC gets the support of barely a third of CAQ voters (31 per cent). Once again, the Bloc Québécois (24 per cent) and the Conservatives (23 per cent) are in a statistical tie for second place. The NDP is a distant fourth with only 7 per cent.

For the sake of comparison, 62 per cent of QLP voters support the federal Liberals, and 75 per cent of PQ voters side with the Bloc Québécois. The CAQ has thus broken the mold of Quebec politics.

Much has been written about the parallels between François Legault and former Quebec Premier Maurice Duplessis, and I will let more knowledgeable historians debate whether this comparison is adequate. Nevertheless, I have been asked on radio stations across the country how and why Quebecers could still support Legault despite Quebec having the worst record of any Canadian province in terms COVID-19 infections and fatalities.

In the much celebrated “Duplessis” TV mini-series (written by Denys Arcand and aired in 1978), long-time Quebec MLA Joseph-Damase Bégin (1900-1977) shares his political strategy with then-former Quebec premier Maurice Duplessis on how to regain in power in 1944 Quebec election. Paraphrasing, he says: “About 40 per cent of Quebecers are going to vote Liberal (Anglophones, Montreal elites, unions), and 40 per cent are going to vote for the Union nationale (rural voters, conservatives), then there’s 20 per cent undecideds in the middle—that’s whom we have to get on board.” (See full clip here.) Premier Duplessis (sublimely played by actor Jean Lapointe) listens and nods, as Bégin goes on: “And how are we going to do that? Nationalism. Nationalism touches everybody, it’s universal, much like a mother’s love. Most importantly, we have it, and the Liberals don’t.” Duplessis went on to win the 1944 handily over the Quebec Liberals and never lost power again until his death in 1959.

According to Quebec historian Jonathan Livernois in his book “La Révolution dans l’ordre: Une histoire du duplessisme“, part of Duplessis’ success was to due to how much space he occupied within the political spectrum: Duplessis was both a nationalist and a federalist, a “social conservative pushing for economic liberalism, and capable of enacting social programs when he believed necessary.” Any politician of any stripe would only dream to scoop voters from that many demographic pools.

Legault has successfully siphoned away support from former PQ voters who, although Quebec independence would still be the ideal outcome, have settled for the CAQ’S approach to governing. As for the QLP, many francophone voters who had been supporting the Quebec Liberals not for their policies, but to stop the PQ from preparing a third referendum, discovered they no longer needed to vote for the QLP and gave Legault’s CAQ a shot in 2018. To wit: In the 2014 election, the Philippe Couillard Liberals had swept all ridings from the Outaouais (5 seats), Mauricie (5 seats) and Eastern Townships (6 seats) regions. Four years later, the CAQ won 12 of those seats, and the QLP was reduced to only two.

Like Duplessis who drove the merger between L’Action libérale nationale (a group of disappointed liberals) and the Quebec Conservatives back in the 1930s, Legault has found the optimal recipe for current Quebec politics: A mix of voters from a wide spectrum of political leanings who are more interested in governing than in fighting decade-old constitutional strifes. The question now is whether Legault’s coalition will manage to remain stable through the turbulent crises (economic, health, climate, etc.) that lurk over the horizon.

Follow 338Canada on Twitter.

* * *

The poll from Mainstreet Research was in the field on Feb. 8-9, 2021 and compiled data from 1,012 potential Quebec voters using automated calls (IVR technology). The margin of error of the full sample is ±3%, 19 times out of 20. The poll was commissioned by 338Canada / Qc125. Find the full report here.