How the election became a game of Balanced Budget Bingo

For the moment, the election depends on how balanced is your budget

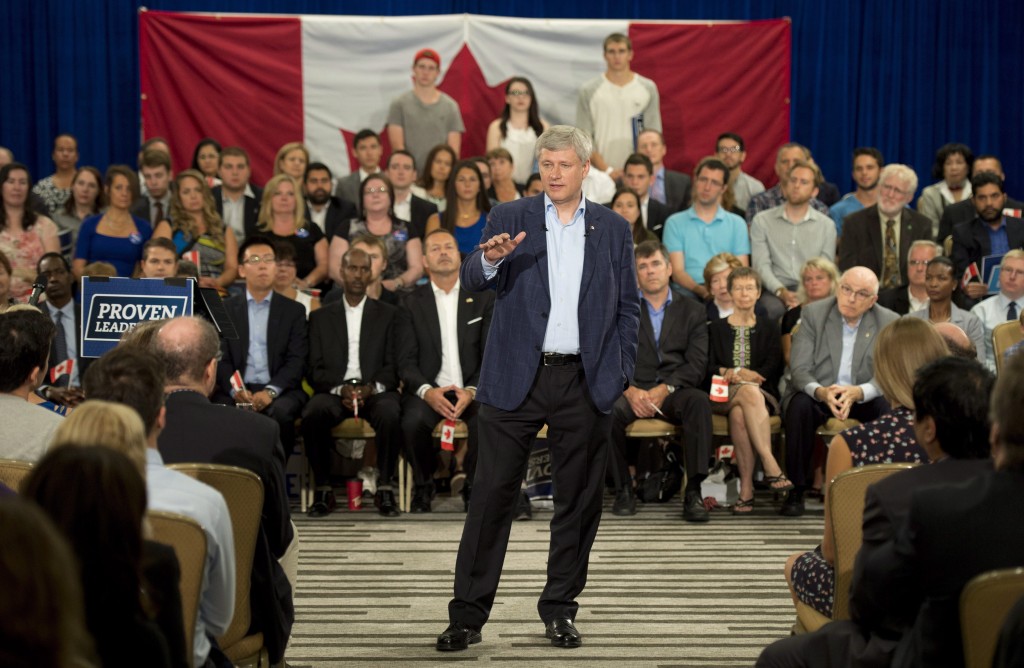

Conservative leader Stephen Harper speaks to supporters during a campaign stop in Ottawa, Monday, August 31, 2015. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Adrian Wyld

Share

“In terms of the education job, I think we’ve done a good job at educating the public to the view that deficits are generally bad,” an economist once said. “We now may be in a period where we have to educate the public to a somewhat less simplistic view. There are occasions where deficits are not only not necessarily bad, they are essential.”

Seven years later we have returned to a simpler time.

“Not deficits, not higher taxes,” the Prime Minister warned this morning, distilling almost the entirety of his pitch to five words. “It’s time to stay the course with our government’s balanced-budget, low-tax plan.”

Insofar as they have planned on eventually balancing the budget, the Conservatives do have a balanced-budget plan. But then by that standard, the Liberals also have a balanced-budget plan.

The difference is that the Conservatives continue to insist that the budget will be balanced in the fiscal year of 2015-16, while the Liberals would have the budget balanced by 2019-20. The New Democrats, meanwhile, are committed to balancing the budget for 2016-17.

And this is apparently now the crux of the entire election. If only because simple math is, well, simple.

[widgets_on_pages id=”Election”]

“A balanced budget is not an end in itself. The reality is that balanced budgets are the foundation that allow a government to put more money into the pockets of hard-working Canadian families and makes you know that you will keep that money,” Harper explained for the benefit of the television cameras set up behind his made-for-TV audience. “Tax hikes take money from your pocket, as you know. Just as importantly, deficits, the kind of routine deficits the Liberal party is now advocating, are just future tax hikes.”

That deficits should necessitate tax hikes is a novel argument so far as it might be advanced by Stephen Harper.

On election day in October 2008, the Prime Minister had allowed an op-ed to appear in the Toronto Star under his byline that ventured that, “We’ll never go back into deficit.” Five weeks later, with a recession apparent, he was of a “less simplistic view.”

His government proceeded to run seven annual deficits, totalling $146.7 billion of new debt.

Next year was to be when the federal budget returned to surplus. But oil prices have dropped and economic growth is sluggish and so government revenues should be lower than expected. And thus the parliamentary budget officer now projects that the government’s accounts will be $1 billion short of balance. Mike Moffatt calculates that the budget might now be in deficit through 2018-19.

These numbers might be of the rounding error variety, but so far as this is a matter of simple math, these are now figures of consequence.

That Harper’s government is anywhere near a balanced budget is nothing to do with the tax hikes that he now warns would be inevitable, but the result of “restraint”—$14.6 billion in annual restraint on program spending according to the government’s accounting, without which a surplus would be nowhere in sight. Perhaps the Prime Minister would have us believe that only he could possibly be so frugal, but four years ago, when his party’s campaign platform booked $4 billion in unspecified cuts, he said it was just a matter of consolidating the government’s computer systems and letting some public servants retire. Budgets don’t balance themselves, but it’s also apparently pretty easy.

A subsequent attempt by the PBO to study the impacts of the cuts was stymied by the government’s lack of disclosure. A comprehensive accounting might be useful now—the PBO has reported that it found no statistically significant relationship between program performance and funding allocation—but in lieu of such a review there is an interesting wager here: that $14.6 billion in federal funding can be eliminated without a statistically significant number of people noticing.

To create its projected surplus for 2015-16, the Conservatives had to sell their shares in GM and take $2 billion from the so-called contingency fund (the PBO’s projection uses all $3 billion of the contingency fund). But both the New Democrats and Liberals might have to stick close to the Conservative government’s discipline to manage future surpluses—at least so long as neither is willing to reinstate the GST’s original seven points. That that might’ve contributed to a structural deficit is a fact all sides would rather not acknowledge.

For now, there is the simple fun of watching the Prime Minister, whose government ran seven consecutive deficits, trying to warn about the peril of running a deficit. And the added fun of watching the Liberal side try to simultaneously mock the Conservative deficits—some of which they encouraged in response to the last recession—while promising three of their own. Further fun may follow when the NDP has to explain how it will balance the budget in a few years. (The New Democrats have historically been keen to remind everyone that their provincial cousins balance their budgets most often.)

As luck would have it, the government’s own balanced budget legislation makes an allowance for the running of a deficit in response to a recession. And by tomorrow morning we may know that we are (or at least were) in one. (That law has the fun bonus of defining a recession as two quarters of the oxymoronic “negative growth,” a definition from which Jason Kenney valiantly tried to run away yesterday.)

“The question for Canadians is what to do with that,” the Prime Minister said today when asked for his own definition (which he avoided providing). “Because of this temporary effect, do we now plunge our country into a series of permanent deficits and tax hikes? We think that is precisely the wrong answer.”

Should a proposal for permanent deficits emerge that will be a point worth debating. Otherwise, the budget balance—whether there is a small surplus next year or a deficit for three more years—seems less an actual matter of consequence than it is a potential measure of character. Do voters, now more educated on the nuances, still cherish a deficit? Does a balanced budget, or at least the promise thereof, constitute credibility and seriousness? Does at least a commitment to balance, and a refusal to entertain a deficit, demonstrate a properly disciplined mind? A day after Trudeau’s pledge, the Winnipeg Sun declared it “political suicide.” And that is surely the conclusion that will be easily drawn if things don’t work out for him.

But, as the Prime Minister says, a balanced budget is not an end in itself. It obviously requires context. And simply adding up the numbers to determine whether revenues exceed expenses only sidesteps the more interesting questions of how funds would be spent or not spent and for what and why. These are decidedly less simplistic matters.