Being Sacha Trudeau

For years, Justin Trudeau’s younger brother, Sacha, led an intensely private life. Not anymore.

Sacha Trudeau near his Montreal home. (Photograph by Will Lew)

Share

When Alexandre Trudeau was in high school, a TV crew showed up one day to ask students their opinions on a political issue; he thinks it was the Meech Lake accord, but he can’t quite remember. Trudeau hadn’t been much in the public eye since he was a child—he was 10 years old when his father, Pierre, retired from politics—so he figured he could offer his views as an anonymous student. He didn’t quite manage to escape notice. “The whole story was about ‘Trudeau’s son,’ ” he recalls. “I just felt violated.”

Trudeau—known to the Canadian public as Sacha, though that suggests a familiarity few have earned—was born into 24 Sussex Drive and escorted to grade school by RCMP officers. He learned from watching his father—an intensely private man who spent years in the spotlight—that public life requires a sort of papier-mâché armour. “You need a token self out there—that self is the one that people hate or love. That’s the self that people feel they own,” he says. “But you don’t put your real self out there—that would be far too painful and difficult.” Trudeau instead chose fierce privacy. As an adult, he virtually disappeared from public view, except for isolated, controlled appearances in documentaries he filmed in far-flung danger zones.

Trudeau, 42, is about to release his first book, Barbarian Lost: Travels in the New China. The book calls up inevitable comparisons to his father, who travelled extensively and wrote about the same country, and his brother Justin, who just completed his first official visit to China as Prime Minister. Trudeau has spent much of his life deliberately—almost aggressively—separating himself from his surname and the political and celebrity expectations that went with it. But it is now, in writing this book and revealing much more of himself, that the youngest surviving son of a dynastic Canadian political family is most independently himself.

Related: The making of Justin Trudeau

At a quiet mom-and-pop Japanese restaurant in downtown Montreal, Trudeau is greeted by the owner as “Sacha.” She complains good-naturedly to him about the construction rattling the building, then invites him to pick a table. The restaurant is just down the hill from the Art Deco residence, formerly his father’s, where Trudeau lives with his family. He’s been coming to this place for decades; they know not to bother bringing ice cream for dessert, because he never eats it.

In conversation, he exhibits a spidery energy and palpable intellect that’s restless and esoteric in nature. He is not a large man; there is both a toughness and a boyish whir to him. It’s easy to picture him surviving handily in a war zone, and also inspiring family matriarchs to insist on providing dinner and a warm bed. His documentary work in places like Liberia, Baghdad and Darfur has relied on both. He doesn’t consider himself a journalist, though he has produced journalistic dispatches, including for Maclean’s. “I am a professional traveller,” he says. “My unique skills are travel.”

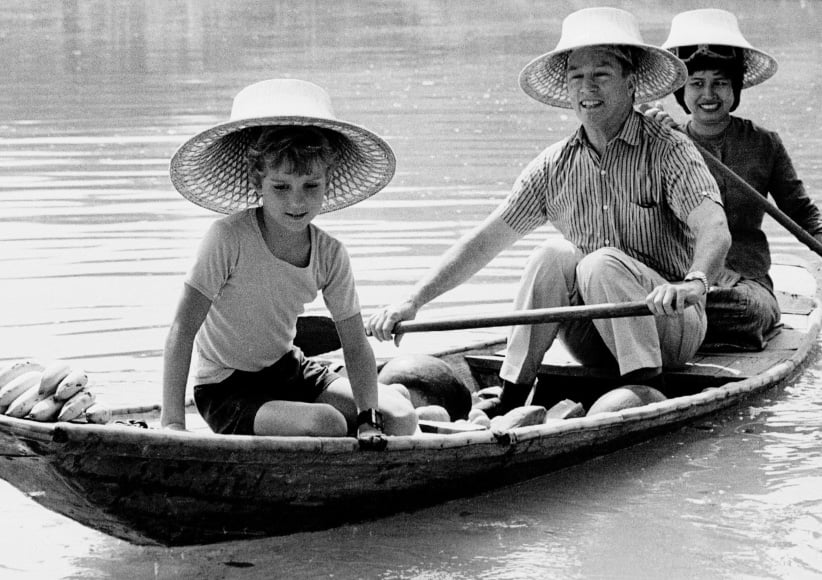

As in his films, Trudeau is present as a character in his book, but he’s not a naive stand-in for a reader new to China; he is instead an informed and opinionated interpreter. Publishers had asked him to write introductions for new editions of his father’s 1961 book, Two Innocents in Red China, and he had so much to say that it sprawled into his own manuscript. China fascinates him as one of the most stable and ancient cultures on the planet, now rocketing through in a single generation the social and economic shifts that took 200 years in the West. “My whole professional career has had a focus on geopolitics, and in this age, you cannot understand the world without understanding the massive role that China has grown to play,” he says.

China represented a transition for Trudeau. The book is based largely on a six-week trip in 2006, though it incorporates material gathered on a dozen trips since. After years in global conflict hot spots, there were a few moments in China when Trudeau had to remind himself that there was no danger, and this wasn’t a place where silence meant bombs were about to fall. He made the initial trip when he and his wife, Zoë Bedos, a clothing store manager, were expecting their first child. Now that they have three young children, Trudeau’s travel patterns and appetite for overt risk have changed, but he continues to relish how the most difficult locations throw everything into relief. “I love that—meeting people and instantly trying to see their motives and their beliefs,” he says. “In the Middle East, that’s the name of the game: you don’t know who you’re dealing with.”

When he was 18, he took off to Africa before starting university. It was a deliberate break with the privilege he’d grown up with, he says, and for a teenager enamoured of apocalyptic tales like Heart of Darkness, it seemed necessary that he himself come close to destruction. “I didn’t want to be young; I wanted to be ancient,” he says. “I felt like the gravest things had to happen to me.” He caught malaria and thought it was an important experience that would age him.

When he returned, he enrolled at McGill University to study philosophy. He used his summers to augment his studies: two years in a row, he went to Germany so he could learn to read German philosophy. The following summer, he enrolled in a Canadian military program that trained students to become commissioned officers. He explains that he was preparing to write his thesis on Heidegger’s critique of Hegel’s dialectical method, then he backtracks and translates that into conversational terms: he was thinking a lot about ways of learning, and the military seemed to him a very old example. It was also a way to test himself by doing something that made no sense. “It was almost a lark,” he says. “Anyone who knew me back then, that’s my great character flaw: I have no capacity for authority.” He surprised himself by loving it, and he took pride in proving to be more than his training officers expected. “They were extra interested in breaking me, because they assumed I’m privileged, soft, I’ve had a cushy and easy life,” he says. He figures if Canada had been a wartime country, he would have become a career soldier. Instead, his year in the Reserves was “like a men’s club,” so he sought discharge.

Trudeau eventually realized that ideas in their purest form were what really interested him, and he concluded that the way to make a career of that was through film. Over the course of his career, he guesses there were three times when he seriously feared for his life. He thinks about the movie The Perfect Storm—he doesn’t consider it a great movie, but there’s a moment when a character contemplates his own impending death and says, “This is going to be hard on my little boy.” That resonates deeply. “It brings tears to my eyes as I say it,” Trudeau says. “But that’s very much what I had in my head: ‘This is going to be hard on my mom.’ These were years when my brother had died and my father had died, and it was, ‘Oh no, I’m going to deliver another death to the family.’ ”

After his younger brother, Michel, was killed in an avalanche in 1998, Trudeau moved in with his father and cared for him at the end of his life. As a child, he can remember startling to the awareness that as vigorous as his father was, he was as old as his friends’ grandparents. Lodged in his young mind was the frightening thought that when his father was 80—the age at which people died, he thought—he would be just 27 years old. As it happened, that’s exactly when he lost his father, in 2000. “It’s a beautiful thing to care for a parent who’s dying,” he says. “It’s the last final piece of great wisdom—to understand we start as innocents and we end there as well. He had taken such good care of me, and I was taking care of him.”

When they sent his father’s body to lie in state on Parliament Hill, Trudeau withdrew to a rural spot to regroup before the state funeral in Montreal. He felt like he had just sent a child off into the world. “I had a moment of, ‘What am I doing? Who am I entrusting him [to]?’ It was a kind of irrational moment of fearing that he was not in good hands, that he would be alone there,” he says. “Then I heard the reports the next day that people lined up, and I was reassured that he was loved.” He was happy for his father, but the public mourning was so different and separate from his private grief that it seemed to have nothing to do with him.

Trudeau is now getting another chance to contemplate the strange relationship between public and private, as he watches his brother in the Prime Minister’s Office. The questions about when he himself would go into politics were once a constant. “People would always ask me,” he says. “Well, maybe less now—now our family has produced what they wanted.” Beyond that dynastic script fulfillment, it’s almost amusing to Trudeau how ill-suited he would be for politics—the Rotary Club types, the gregariousness, the need to compromise and negotiate. Growing up in the spotlight left reverse imprints on him and his brother. “To a certain extent, I was ashamed of being a prince, and he’s embraced it, used it,” Trudeau says. “The person I chose to be is the one who’s hitchhiking in the rain in January in Israel, trying to get work on a farm. It’s so much realer to me.” The commonality, he says, is that both he and his brother have a purpose in mind. “I’m not sure I agree with this turn in politics, but it certainly is the mainstay one—the movie-star politician is a formidable force in this kind of world. Maybe a dangerous one, in the long run,” he says. Asked if he freely opines to his brother about this, he laughs: “I tease him about it, maybe.”

Justin Trudeau has said that he is most like his mother, Margaret—emotive, spontaneous, drawn to other people. The obvious deduction is that intense, cerebral, interior Alexandre is like his father, but when asked for his own assessment, he initially bats the question away. Later, he says his mother sees him as exactly like his father. “I was very close to my father and remain very close,” he says. “I live in his home, I’m the guardian of his private spirit.” There are significant differences, too. Trudeau is handy around the house, while hands-on skills eluded his father, but he sees his father’s intellect as grounded in politics and law, while pragmatics don’t interest the younger Trudeau. He has one of those brains that’s always going, and he’s learned that occupying himself physically is the best “off” switch. He swims and gardens and loves to cook—Japanese food in the winter, when he has more time for elaborate preparation, and Thai, Argentine or Chinese in the summer, when more of life is spent outside.

In part through his book, he’s arrived at a certain peace with how the Trudeau part of who he is fits with the pieces that are entirely his own. “At different times in my life, it annoyed me that my identity was so connected to that of my father,” he says. But now, he’s “embraced my own Confucianism” and landed on a different idea: being linked with his father is not just normal, but honourable. Delving into Chinese culture was part of arriving at that, but it was also a product of Trudeau accumulating experience and simply becoming the person he wanted to be. “As time goes on, there’s a kind of joy to have him alongside me,” he says of his father. “There’s room in my world now—long after him, and he’s gone now—for him.”

Now that Trudeau is a parent, his perspective is a zoomed-out one: he believes we exist as bridges between the people who came before us and those we are helping to launch into the world after us. “I think the Chinese view of that is the safest and surest one: we’re all immortal insofar as parts of us remain, and parts of those who preceded us remain in those who come after us,” he says. “We’re sort of carrying it all, passing it along. I think that’s beautiful, and true.”