Freeland says Trump’s tariffs are illegal, but don’t expect a U.S. court to listen

Legal experts explain why a World Trade Organization case, although slow, is a better bet than trying to use the U.S. law against Trump

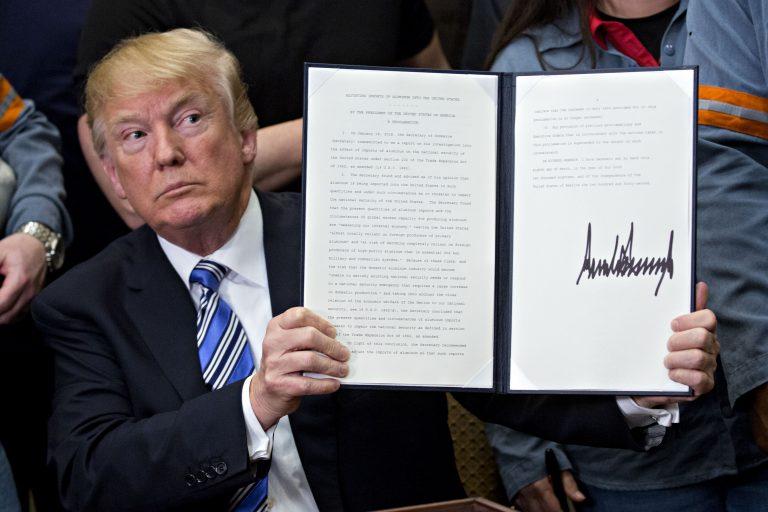

U.S. President Donald Trump holds a signed proclamation on adjusting imports of aluminum into the United States in the Roosevelt Room of the White House in Washington, D.C., U.S., on Thursday, March 8, 2018. (Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Share

When Foreign Minsiter Chrystia Freeland rails against the tariffs U.S. President Donald Trump has imposed on Canadian steel and aluminum, one word stands out: illegal.

Her complaint that the tariffs are unfair, or her lament that they cut against the great American tradition of support for liberalized trade, might be persuasive, but those sound like subjective arguments. On the other hand, when Freeland flatly declares that the tariffs are against the law, it sounds more like an objective claim of the sort that might be tested in court.

However, trade lawyers doubt that’s going to happen—at least, not in an American court. Here’s the problem: Trump’s pretext for the tariffs is that steel and aluminum imports—including imports from close allies like Canada and European democracies—threaten America’s national security. He’s wielding Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, under which Congress gave presidents the authority, way back when John F. Kennedy was in office, to impose tariffs where national security is threatened.

Trump’s own comments undermine his claim that the tariffs are really about national security. He has bluntly linked them to Canada’s protection of its dairy sector and to lack of progress in the NAFTA renegotiation. That leaves little doubt that he’s exerting pressure for concessions on other trade fronts. Yet lawyers on both sides of the Canada-U.S. border doubt any U.S. judge will be eager to consider the argument that Trump is abusing the Section 232 authority.

“I think it is extraordinarily unlikely that any U.S. courts would get involved in deciding that question,” says Joshua Zive, a Washington-based trade lawyer with the firm Bracewell. He points out that since Congress delegated the Section 232 powers to the president, Congress could also act to restrain a president who was seen as misusing the power. “Courts are loath to step in and do the work that Congress will not do,” Zive says.

READ MORE: Donald Trump’s tariffs don’t protect American security—they jeopardize it

(In fact, Senator Bob Corker, a Republican from Tennessee, who chairs the Senate’s foreign relations committee, has led a push for Trump to be required to seek congressional approval before using Section 232 to impose the tariffs, but Corker doesn’t appear to be getting enough support to pass his bill.)

The Canadian government seems well aware that counting on Congress to step in, or fighting Trump in the U.S. courts, are at best long shots. Freeland has focused instead on international trade dispute-settlement processes. “The 232 tariffs introduced by the U.S. are illegal under WTO and NAFTA rules,” she said in a speech in Washington this week. “They are protectionism pure and simple.”

Indeed, Canada is among the raft of countries that have already filed challenges against the steel and aluminum tariffs at the World Trade Organization. Riyaz Dattu, a Toronto-based trade lawyer with the firm Osler, says the WTO is a better bet than the North American Free Trade Agreement’s process. The WTO process can usually be completed in about 18 months, whereas the timeline for reaching a conclusion under NAFTA would be much harder to predict.

As well, Dattu says Osler expects the WTO to be open to hearing arguments about presidential discretion that the U.S. courts would be reluctant to delve into. “The preliminary research we’ve done,” he says, “suggests the WTO would likely question the factual basis of the claim that there’s a threat of injury to national security.”

The WTO agreement does allow countries plenty of leeway to impose tariffs for security reasons “in time of war or other emergency in international relations.” But there’s obviously no war involved in this dispute, and Larry Herman, a veteran Toronto trade lawyer, says there’s no real emergency either. “Ironically, if there is an emergency in international relations, it’s Trump himself, by using Section 232, who has created it,” Herman says.

A victory for Canada the WTO, though, wouldn’t have nearly the direct impact of winning in a U.S. court. “The WTO will not have the power to reverse any of these actions like a U.S. court would,” Zive says, “but they certainly have the power to authorize retaliatory tariffs.”

And that would be a hollow victory for Freeland and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. After all, they have already announced Canada’s intention to impose retaliatory tariffs on July 1—far in advance of any WTO ruling. “Pursuing a WTO case will emphasize that even though we took the counter-measures on a premature basis, under the WTO rules they were justified,” Dattu says.

In other words, Canada might be vindicated, but nothing much would change. Still, trade lawyers who don’t like what Trump is doing assign serious value to the WTO case, even if it doesn’t end up having much practical impact. “The U.S. might snub their noses at a WTO ruling and ignore it, and they probably will,” says Herman. “But it would be an important victory.”