In his bid for the presidency, Joe Biden is stuck in the middle

The consummate pragmatist has been courting progressives—and a lot of risk

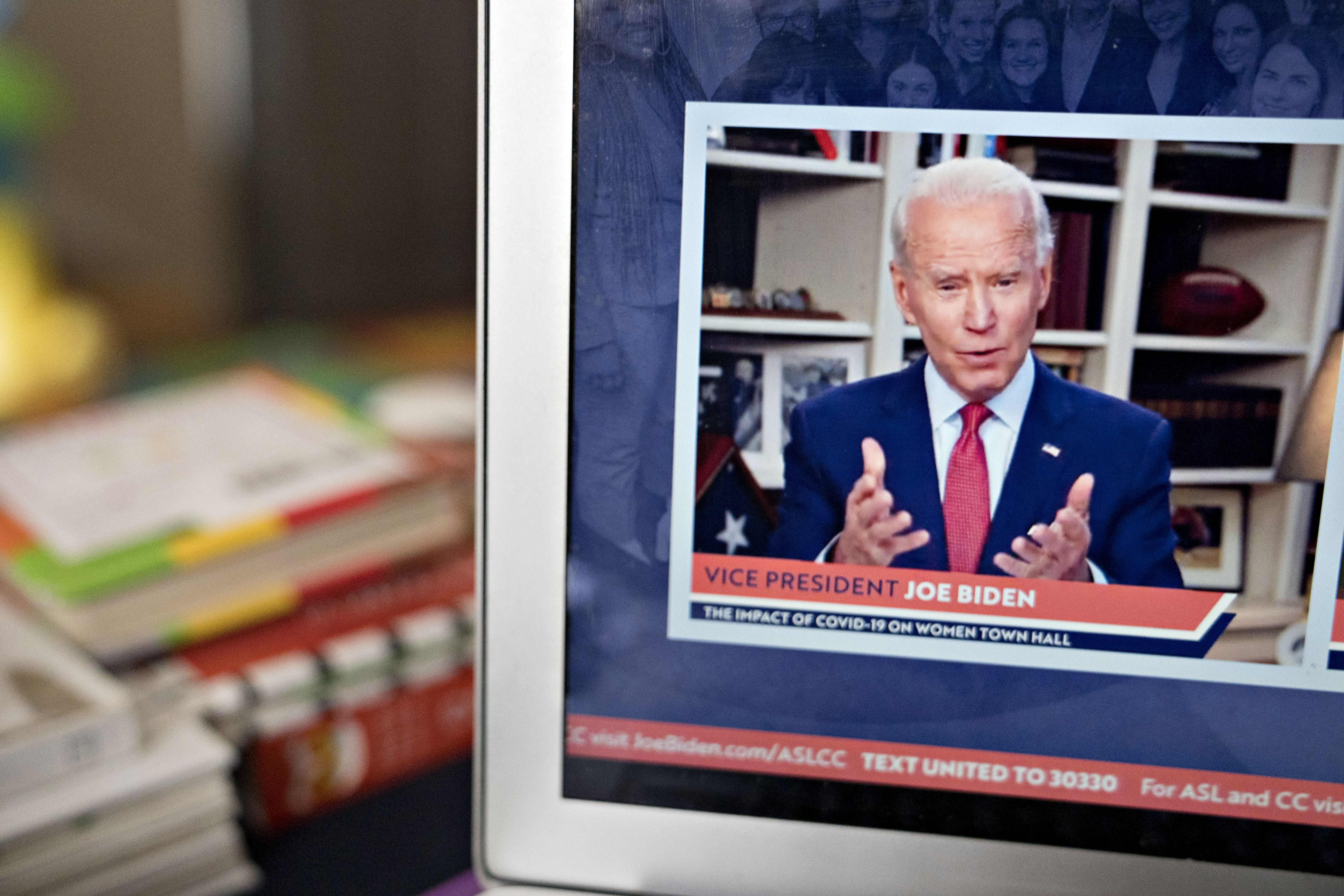

Biden must find a way to appeal to younger voters, lest they vote Green or not at all (Craig F. Walker/The Boston Globe/Getty Images)

Share

On April 14, to no one’s surprise, Barack Obama endorsed Joe Biden for president of the United States. The former president came off as eloquent and calming throughout a 12-minute video—also unsurprising, as he clearly wishes to fill a Donald Trump-sized chasm in the hearts of worried Americans. Obama emphasized Biden’s role in helping the U.S. recover from the last recession—more predictable praise, given the looming post-COVID-19 economy.

Then, six minutes in, Obama said something that took many off guard. After praising Bernie Sanders, the democratic-socialist senator and erstwhile Biden rival, he claimed that Biden “already has what is the most progressive platform of any major party nominee in history.”

Really? How could Obama claim that Joe Biden—a man who argued repeatedly for the government’s right to cut Social Security over his years in the Senate, who voted against busing for desegregation decades ago, who has fundraised millions of Wall Street dollars for his current campaign, who infamously backed the Iraq War—how could this guy helm the most progressive platform in American history?

There is some merit to the claim—albeit the kind that plays best in debating societies. PolitiFact, a fact-checking site run by the non-profit Poynter Institute for Media Studies, calls it “half-true,” noting that Biden wants to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour, erase past marijuana convictions, shut down private prisons, abolish the death penalty, create a national firearm registry and implement a study into reparations for slavery. He also loudly committed to naming a woman as his running mate, and a Black woman to the Supreme Court. Objectively, these are the most progressive policies Americans have seen in their country’s 243-year history.

READ: Can Joe Biden win the presidency from his living room couch?

The counter-argument: The definition of “progressive” in 2020 isn’t what it was 243 years ago, or even 10 years ago. The title of “most progressive” can only be examined contemporaneously, not retrospectively. George McGovern, who suffered a huge loss to Richard Nixon in 1972 (fun fact: the same year Biden was first elected to the Senate), pushed an aggressively liberal agenda for his time, including withdrawal from the Vietnam War, amnesty for draft dodgers, a 37 per cent reduction in defence spending over three years, and other environmental and crime policies that, while status quo today, were deemed radical in their day. The question, then, isn’t whether Joe Biden is more liberal than any of his predecessors, but whether he’s more liberal than any of his contemporaries. That answer is obviously no.

Neither interpretation is wrong. According to David Barker, director of the Center for Congressional and Presidential Studies at American University in Washington, D.C., Biden’s progressive promises are less about social progress than frank popularity. “That is how Biden has always operated; he modulates his positions based on where the median American voter is,” Barker told Maclean’s in an email. “In that way, he has always been squarely in the centre of the Democratic party ideologically, wherever that centre has been—never a lefty and never a true ‘centrist.’ ”

That delicate spot, squarely in the middle of a never-ending tug of war between moderates and progressives, is precisely where Biden finds himself trapped right now, as he draws up his platform in the run-up to the November election. Appease the frustrated far left, and he risks alienating the middle; pander too much to the middle, and progressives may simply stay home. For Democrats, this decades-long conundrum—how to advance a liberal agenda without scaring off middle-of-the-road voters—has taken on existential implications. Three and a half years ago, a moderately progressive agenda led by the first-ever female nominee pushed middle-of-the-road voters in key swing states into Trump’s arms. Has anything changed?

The greatest flashpoint between progressive and moderate Democrats has been Medicare for All, the health-care overhaul pushed by Sanders that would abolish private insurance companies and bring all Americans into a single-payer system. A recent countrywide poll conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation, an independent non-profit health-care organization, found support among 56 per cent of respondents for Medicare for All, but fully 68 per cent for a so-called “public option,” which is what Biden is proposing. That would allow anyone to buy into Medicare, an affordable program currently available only to seniors.

Still, despite the support, Biden has not etched his health-care plan in stone. Shortly after Sanders dropped out on April 8, crowning Biden the presumptive nominee, Biden’s camp shot out two policy proposals ostensibly targeting the Berniesphere: He would lower the age of Medicare from 65 to 60 and forgive student debt for low-income and middle-class individuals who attended public post-secondary institutions and historically Black colleges. In the media, this twofer was widely construed as an “overture to the left,” which sounded odd, since virtually every other presidential candidate, after clinching the nomination, shifts toward the centre. (The theory is that party members on the extremes will vote for you anyway, so you need to start working on undecided centrists and independents.)

In reality, diehard Sanders supporters were not impressed by those policies. “Biden struggles with younger voters,” says Luke Savage, a Canadian staff writer at Jacobin, a democratic-socialist magazine based in Brooklyn. “He doesn’t struggle with older voters—that’s his base. Lowering the Medicare age eligibility by five years isn’t really courting Sanders supporters.” (Young progressives—especially women—may be even more skeptical of Biden after a former aide, Tara Reade, accused him of sexually assaulting and harassing her in the early 1990s. Biden has denied the allegations and prominent Democrat women seem to be rallying around the candidate rather than his accuser.)

READ: Joe Biden:’For those that have been knocked down, counted out, left behind, this is your campaign’

Optimistic progressive Democrats have portrayed this as merely a first step in a years-long battle. They’re hopeful about six joint task forces established by Biden and Sanders in April—on climate change, health care, criminal justice, immigration, the economy and education—that comprise members of both camps, which could lead to further leftward policy shifts.

Even if Biden adjusts his messaging, however, those platforms are unlikely to replace any of his current ones, because—as with his health-care strategy—they’re poll-tested and popular. According to Ryan Pougiales, a senior political analyst at Third Way, a centrist Washington-based think tank, Biden was merely throwing a bone to the left with his Medicare age-lowering compromise. “Biden’s health-care plan, essentially, is a Medicare public option. So literally anyone has the option of buying into Medicare.” Any adjustments he makes between now and November will not substantially change that.

Still, the outreach is meaningful, and it extends beyond Sanders. In mid-March, Biden absorbed Elizabeth Warren’s progressive proposal on bankruptcy reform, which would help middle-class Americans move on with their lives more quickly after declaring bankruptcy by waiving fees and protecting them from looming debts.

Democrats across the spectrum point to this consolidation as proof of a quality unknown in today’s White House: the candidate’s ability to listen. While critics blast it as flip-flopping, others hail it as open-mindedness crucial to building a strong coalition. Against Donald Trump’s authoritarian tendencies, it may be Democrats’ greatest weapon. Say what you will about Joe Biden—and he’ll hear you out.

***

Hours after Sanders dropped out, eight progressive youth organizations signed a public letter addressed to Biden, and published it on the website of Tom Steyer’s climate organization, NextGen. The letter is a blueprint for the program that Gen Z, democratic socialists and their progressive allies are hoping Biden will adopt: support Medicare for All, cancel all student debt, legalize marijuana. Biden will almost certainly not do any of that.

But some requests overlap with what he has already promised. For example, the NextGen authors want him to repeal the Hyde Amendment, which prohibits Medicaid dollars being used for abortions; Biden formerly supported the amendment, but openly changed his mind last June. They want greater accountability and transparency for border patrol guards while expanding the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program; his website promises he will do both. The letter makes no mention of a $15 minimum wage—a moot request, since Biden (following Sanders’s lead) is already on board.

One could envision the former veep shifting left on other files. His website sketches plans—albeit watered-down versions of what the NextGen authors want—for investing US$20 billion in crime prevention over incarceration, and laying out a framework for the Green New Deal. Around the same time Biden adopted Warren’s bankruptcy proposal, he picked up a 2017 Senate bill, led by Sanders, which would make public colleges and universities tuition-free for students coming from a household with an income less than $125,000.

[contextly_auto_sidebar]

Promises, however, are one thing; actions are another. Progressives cried out when Biden named Larry Summers, the former president of Obama’s National Economic Council, who enjoys close ties with Wall Street executives, as his economic adviser. Serious progressives care as much about appointments as they do about policy. “We’ve encouraged the Biden campaign to bring on personnel in the campaign, transition and presidency that are committed to fighting for people, not corporations or Wall Street,” Chris Torres, a political director at the progressive organization MoveOn, told Maclean’s in an email.

By including establishment Democrats in his cohort, Biden will never win over all Sanders supporters. But looking at the data, one has to ask: Why bother trying? A Morning Consult poll of 2,300 Sanders fans found that 80 per cent would vote for Biden in November. And while democratic socialists often point to Biden’s weakness among younger Americans, who skew progressive, multiple polls from March all showed Biden beating Trump among millennials by at least 10 percentage points. Even if those predictions don’t come to pass, younger voters are statistically less likely to vote than older ones, who skew conservative. Crunching the numbers in Vox, the journalist Matthew Yglesias summarized it mathematically: “Every voter on the margin between Democrats and Republicans is worth twice as much as every voter on the margin between Democrats and the Green Party.”

Yet Biden cannot ignore young Americans, for fear that they might actually vote Green, or not at all, and spoil the outcome in critical states. “The delicate political calculation he has to make is how far he can go to mollify the progressive wing,” says Matthew Dickinson, a political science professor at Middlebury College in Vermont. He points to Biden’s electability argument, that he can win back the disenchanted middle- and working-class white voters in Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania who swung to Trump in 2016 after decades of supporting Democrats. “The issue that really divides those Trump supporters is a sense of fairness. They think that the rules have been stacked against them. And anything that smacks of favouritism or elitism, or elevating one group over the concerns of other groups, they tend not to support.” For Biden to win back the Rust Belt, he’ll need to convince voters that a $15 minimum wage, public option and criminal-justice reform are in fact equitable policies.

Luckily for him, that argument may be easier to make in 2020 than it was in 2016, due to the seismic shift brought about by COVID-19. Terry Moe, a political science professor at Stanford University, believes we’ve been living in a post-Reagan world for decades, where conservative politicians successfully run on anti-government policies, promising retrenchment, lower taxes and less red tape. In the same way the Great Depression led to Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s, he says, the current pandemic proves how badly we rely on well-funded, effective government. “This could be the beginning of a new political era in which politicians run on agendas that promote government capacity and government action in solving social problems,” Moe says. “That is the progressive agenda.”

Democrats will likely link the concept of a strong and equitable government to everything Trump opposes, harkening in some ways to the anything-but-Trump campaign of 2016. The message may sound more convincing after a devastated economy compounds the chaos of Trump’s last four years. With a pragmatic, fair, progressive-lite platform, they might be able to convince enough voters to join the blue team.

Policies this early have never been about affecting real change, anyway. They’re about hope. And at this point, with no standard-bearer left to fight for them, hope is all progressives have.

This article appears in print in the June 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “What’s left to Biden.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.