Joe Biden: Hope, unchanged

Paul Wells on the launch of the former vice president’s ‘American Promise Tour’—an exercise in grieving and the start of a presidential run

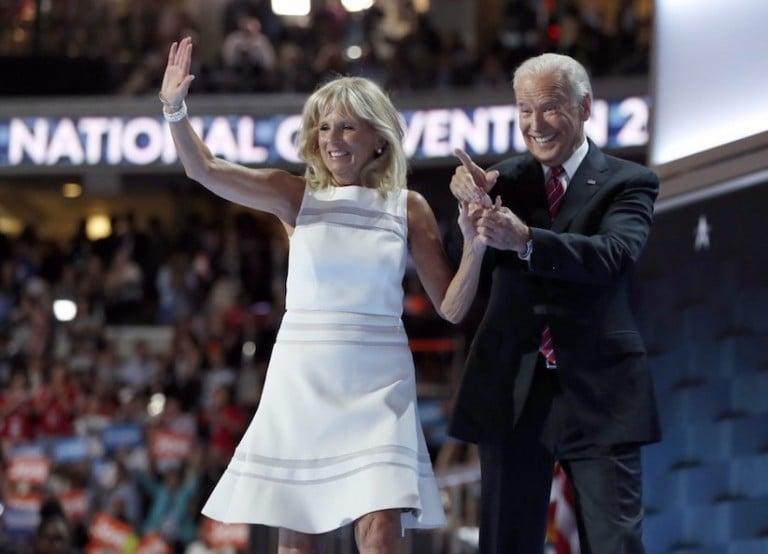

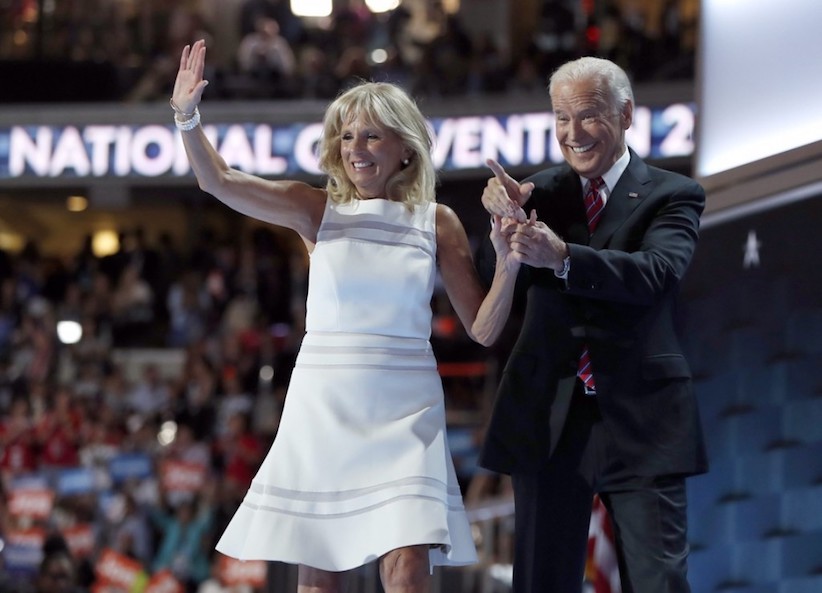

Dr. Jill Biden and Vice President Joe Biden wave after speaking to delegates during the third day session of the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia, Wednesday, July 27, 2016. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Share

Here’s Joe Biden mourning his dead son. Here’s Joe Biden running for president. I can’t tell the difference. Can you?

By the time the 47th Vice President of the United States of America strode onstage at the David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center in New York City on Monday evening, the launch of his 16-city American Promise Tour was already reminiscent of a major political party’s presidential nominating convention.

First came the video highlighting the candidate’s—sorry, I mean the retired 74-year-old’s—career accomplishments, artfully interwoven with high-profile endorsements. “If you can’t admire Joe Biden as a person,” Barack Obama says in one clip, “You’ve got a problem.” Their shouts of approval suggested just about the entire Lincoln Center crowd agreed. Surely even in this polarized American hour, most Americans do too.

Then Biden’s wife Jill marched out to a lectern at stage left. Suddenly the evening diverged from the convention script. “It’s been tough,” she told the crowd. “But you all carried us when I thought we couldn’t go on.” She thanked assorted Biden children and grandchildren for supporting the family patriarch as he wrote the slim book that had been distributed to each audience member once they had cleared the venue’s metal detectors.

“This was a hard story to tell, and one he had to get right,” she said.

The book in question is Promise Me Dad: A Year of Hope, Hardship and Purpose, released Tuesday. It’s Biden’s account of the year his son Beau Biden died of cancer. A quick read suggests it’s a genuinely affecting tale of a father’s worst nightmare. But it’s more than that, or it’s simultaneously that and something else entirely.

READ: Barack Obama surprises VP Joe Biden with Medal of Freedom

At the end of the book, in early 2016, Biden decides against a third run for the presidency, after unsuccessful attempts in 1988 and 2008. It’s a wrenching decision. This time he would have run from the best possible launch position, as the vice-president of a popular president. He would have been fulfilling a dying wish of his son, a popular Delaware state politician who would, Biden feels sure, have run for president himself one day. As the book ends, its author has said nothing definitive about his future. He has already suggested he’s revisiting his decision. Three days before Donald Trump’s inauguration, Biden told an interviewer that in 2020, “I’ll run if I can walk.” It’s a big if. He’ll be 78 on inauguration day in 2021. It would make him by far his country’s oldest president, older by nearly eight years than Trump, who was older by a year at his inauguration than Ronald Reagan.

So what, precisely, was the near-capacity crowd at Geffen Hall there to do? Meditate on grief or rally around a champion?

Wearing a navy suit and looking hale, Biden plunked himself down in one of two plush chairs at centre stage. Stephen Colbert, the television talk-show host, took the other. Colbert does not like to keep an audience guessing about whether he likes an interview subject. “I just want to say that, you know, people love Joe Biden,” Colbert said. The audience roared its agreement. Colbert continued: “And Joe Biden loves people!”

The next hour of conversation, while not scripted, covered a lot of ground briskly and in orderly fashion. What’s he been up to? Biden mentioned new Biden Institutes at the Universities of Pennsylvania, for foreign affairs, and Delaware, for domestic policy (delighted squeals from Quaker and Blue Hen alumni in the crowd). He said he’s still trying to help researchers cure cancer.

Does he miss politics? “I do. I enjoyed politics. I enjoyed being a senator.”

What’s the book about? “It’s basically to find purpose,” Biden said. When you’re dealt a crushing blow like the death of an adult child, you need a reason to go on. Biden asked the audience how many of them have had similar losses. Hundreds of hands went up.

“You know,” Biden said. “You know. You’ve got to find purpose.”

He’d poured himself into writing the book. “It surprised me. I didn’t realize how much I’d put out of my mind—that I didn’t want to remember.” He’d repeat something he remembered Beau saying to his other son, Hunter. “Dad, Beau couldn’t say that,” Hunter would reply. “His throat was full of tubes.”

Biden’s first wife and daughter died in an automobile crash in 1972. Writing the new book “reminded me how long it took to deal with it the first time.”

The book’s title is a line from one of their last conversations. “I’ll be all right,” Beau had told him. The Bidens are a big Catholic family. “But promise me, Dad, that you’ll be all right.” Biden took this as an admonition to resist the urge toward introversion—to “stay engaged” instead.

Colbert spotted a cue for a pivot. How, he asked, has writing the book affected Biden’s sense of purpose? “Well, it’s intensified it,” Biden said. And with that Biden was clear of the precincts of grief and free to romp more or less uninhibited in the sunlit uplands of political commentary.

Does anything in today’s U.S. politics give him hope? Why, yes it does, and he began by listing two Republicans. “Start with my friend John McCain,” Biden said. He added “a guy who’s probably not getting enough credit,” Republican senator Jeff Flake, who’s already announced he won’t run again and is serving out his term as a persistent Trump critic. This was deft. In a country whose politics often seem to have degenerated into a war of all against all, here was a Democrat naming two nominal opponents when asked for heroes.

Who else did Biden want to compliment and, by implication, associate himself with? The military. “They do it every single day.” Millennials. (Millennials?) “The most open, the most engaged, the most tolerant generation in American history.”

By this point Colbert was sailing one lob after another right over the plate. What advice might Biden have for discouraged voters? Turned out he had advice! “Folks. Folks. There’s nowhere to hide.” A call to service. “You can’t build a wall high enough to make the environment cleaner. You are diminished when your sister can’t marry the woman she loves.”

The Trump presidency is not a joke anymore, he said. “What started out as bemusing or somewhat distasteful—people are now genuinely worried about the fate of our democratic system.” At this, Colbert’s hand drifted slowly upward like a shy student’s. The crowd laughed. Biden ignored the distraction. He was just getting wound up.

America has all the attributes of a great country, he said, mentioning natural resources and “research universities” and—and—and “venture capitalists.” “What drives me crazy is that we’re squandering it right now. We’re squandering it. And you think you’re tired? Get up. Just get up.”

There was a detour into autobiography-as-credential-setting. What was it like working with Obama? “When he gave me authority, I had absolute authority,” he said. “I was calling the shots.” Once at a senior staff meeting, someone had put a question about Iraq to the president. He’d pointed at his veep, all casual, just like that: “Joe gets Iraq.” The Obamas and the Bidens were super-close. Still are. He’d talked to the ex-president on that very day. His granddaughter Maisy “is Sasha’s best friend in the world.” The two families weren’t just friends. “It became a family. But it’s because the value set is the same. The value set.”

Does he talk to his successor, Mike Pence? Sure he does. Would he rather see a President Pence than a President Trump? “I’d rather see a President Clinton.”

READ: Joe Biden’s speech to the 2016 Democratic National Convention

Colbert, no fool: “Or a President Biden?”

Biden just sat there, smiling sheepishly, while the crowd applauded and offered its endorsements. “We need you, Joe!” a guy behind me shouted. The Schrödinger candidate, his political career simultaneously finished and thriving, was in no mood to clarify his thinking just yet.

Colbert threw him a lifeline. “In some crazy alternative reality where you don’t run in 2020,” did he think the Democrats could find a good candidate? Biden mentioned Massachussetts senator Elizabeth Warren with no great enthusiasm, and New Jersey senator Cory Booker with more. He mentioned Kamala Harris, the new senator from California, and Sherrod Brown, the senior Ohio senator. Colbert asked about Bernie Sanders. “Bernie struck a chord that is consequential,” Biden allowed listlessly. “Look, the income inequality in this country is unsustainable.” It was the first time in more than an hour he had mentioned income inequality. Sanders can effortlessly regale a crowd for an hour on the theme. The mutual incomprehension between the Democrats’ Sanders wing and its establishment wing remains complete.

Biden has to know this talk about who might run for his party in 2020 contains in it the germ of the end of his own dream. Three years out, it’s impossible to know who’ll run, or who the party will want. In 1999 I visited the Iowa Republican Straw Poll, an entertaining event on a state fairground that served as the unofficial kickoff for the next year’s presidential election campaign festivities. George W. Bush was there, but he was only one of several candidates getting a serious look from the state’s GOP base. Lamar Alexander, who’d put a scare into Bob Dole in 1996, was there. Dan Quayle, who’d once been a vice president and who still thought that meant something he could benefit from. Elizabeth Dole, whose walk-and-talk on the floor of the 1996 San Diego Republican convention had briefly outshone her own husband’s candidacy.

Each of them had walked through fire to get this far. Each had a dream and at least the rough foundation of a reason to believe. None but one made it to the big desk in the Oval Office. A lingering sense of justice and decency has left millions of Americans feeling that fate owes Joe Biden something. But fate is cruel, as perhaps only a man on a speaking tour about his own son’s death can understand.

Maybe Joe Biden will run again. He might even win. Stranger things have happened. On Nov. 8, 2016, that sentence became authorized for use in any discussion of presidential politics, lo unto the end of days. For now, Biden is a reminder that politics can be redemptive—or that it is, at least, permitted to wish it could be.

MORE ABOUT JOE BIDEN: