The broken triumph of Justin Trudeau

Paul Wells: Why does it feel like the country isn’t any better off after this election? Perhaps because the problems Canada faces demand hard choices, and modern election campaigns reward denial and emojis.

PM Trudeau speaks with staff on the campaign bus in Mississauga. September 11, 2021. (Courtesy of Adam Scotti/Liberal Party of Canada)

Share

“Some have talked about division,” Justin Trudeau told a little victory party in Montreal on Sept. 20, election night. “But that’s not what I see. That’s not what I’ve seen these past weeks across the country.”

The Liberal leader had just won his third consecutive federal election, a feat that, in his lifetime, only Pierre Trudeau, Jean Chrétien and Stephen Harper had matched. And now he was marvelling at the unity of Canadian purpose and spirit.

Except, you know, it’s a funny thing. Barely three weeks earlier Trudeau had stood before reporters in Bolton, Ont., discussing a planned campaign rally that had been cancelled because of security concerns over anti-vaccination protests outside. And in Bolton, he’d seen division. “I’ve never seen this intensity of anger on the campaign trail,” he’d said then. “We need to hear the fears and the disagreements and the concerns that Canadians have—by listening to each other.”

This was great advice in August, forgotten by September. As an isolated case, Trudeau’s little rhetorical reversal—unprecedented division that must be heeded, followed by none at all that he could see—was trivial. Who doesn’t speak in approximations?

But of course there were other examples of Trudeau, and other pols from all parties, ignoring the complexity of the real world for the bracing simplicity of campaign rhetoric.

“Thank you, Canada,” Trudeau wrote on Twitter after the vote, “for putting your trust in the Liberal team.” In fact fewer than a third of voters had put their trust in his team. The Liberals had won a plurality in Parliament with a lower share of the popular vote than any other winning party in history. This odd feat of efficiency extends some impressive trends. The Liberal share of popular vote has declined in six of the seven elections since 2004: only Trudeau’s first win, in 2015, saw the party’s share of vote leap upwards, so it could start drifting downward again. The Conservative Party of Canada has won more votes than the Liberals in five of the last six elections. We count seats in Canada, not only votes, so the Conservatives have been out of power since 2015 fair and square. But “trust in the Liberal team” is hardly the only thing going on here.

READ: Justin Trudeau’s victory speech: ‘Our government is ready’ (Full transcript)

Still, Trudeau’s third victory will have real consequences. Just because an election is close or divisive doesn’t mean it doesn’t settle big things. An election in which voters pass up a chance to choose change is still very far from being an election about nothing. Trudeau’s government returns to work with a mandate to impose vaccine requirements in federal workplaces, trains and planes. It will proceed with a plan to triple carbon taxes and the rebates that go with them, in provinces that don’t have ambitious carbon-pricing regimes of their own. It has the go-ahead to keep building a national network of low-cost daycare spaces.

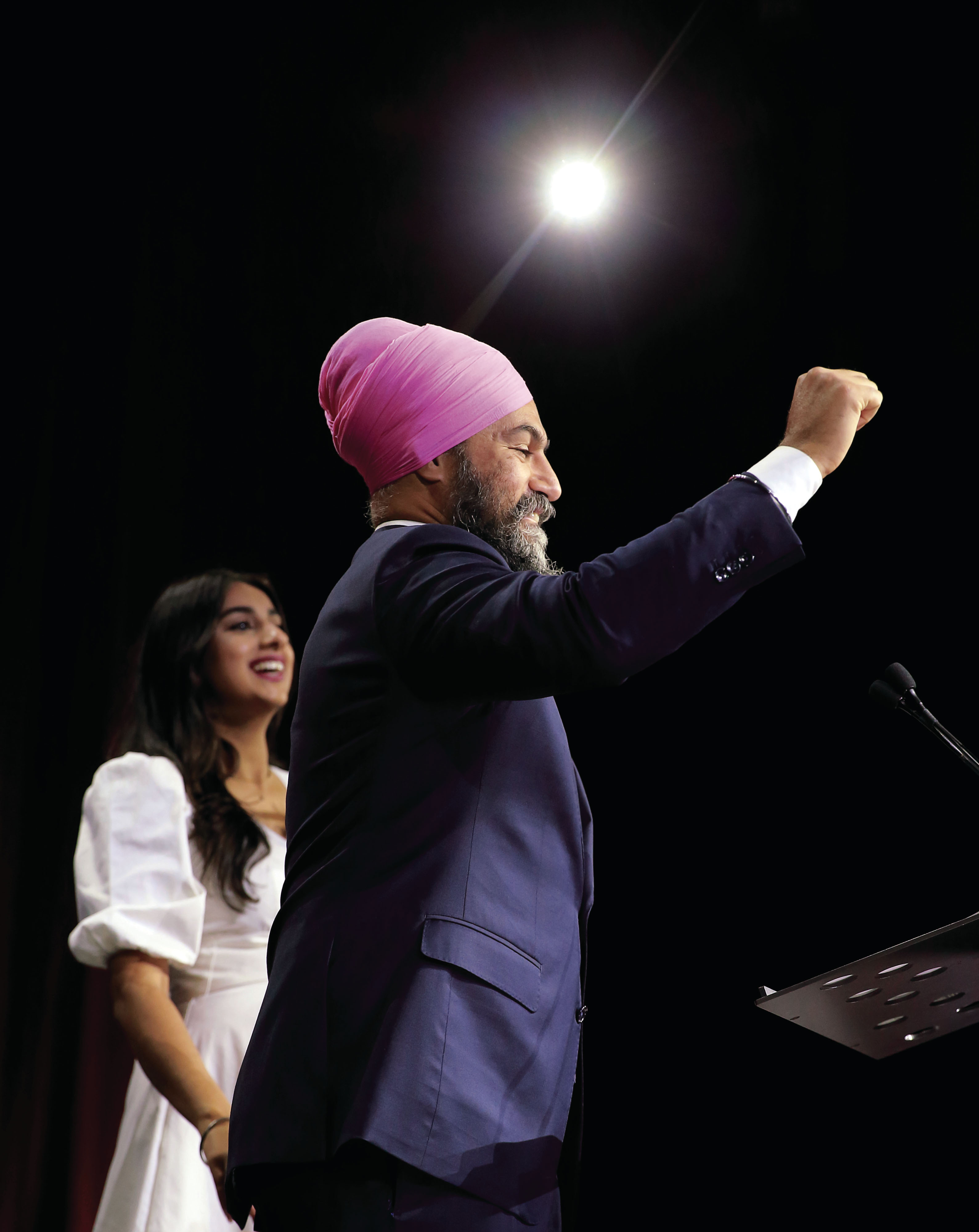

Clear alternatives got a real hearing in the campaign. Erin O’Toole’s Conservatives, Jagmeet Singh’s New Democrats and Maxime Bernier’s populist, outsider-shtick, one-man act took turns surging in the polls. If any had withstood the ensuing scrutiny better, each could have made a sustained breakthrough. That none did suggests Canadians who had considered switching their votes finally decided they preferred the Liberal they knew.

So Trudeau’s victory is legitimate and impressive. It sets a distinct course for the country on things that matter. Why, then, do so many people feel the country isn’t any better off for having dragged itself through this campaign?

Perhaps because the problems Canada faces demand realism and hard choices, and the dynamics of a modern campaign reward denial and emojis. Everyone hopes these are the waning days of a historic catastrophe nobody anticipated the last time we voted in 2019. We could actually use a real discussion about what happens next. Is it masks for everyone forever? Is there a quantum of risk that’s low enough that we can get back to living more or less the way we used to? Are we anywhere close to that blessed day?

How do we blunt the terrible force of the next catastrophe, given that the next catastrophe may not be a coronavirus or even a disease?

How do we “build back better,” given that there’s actually not much building back to be done? I mean, look out a window. The world of 2019 is still there, dusty but intact. This isn’t 1945. Stop saying it’s 1945.

It would be great if we could have adult conversations about these things, about hard choices and limited payoffs. But the very best that can be said for election campaigns is that they obliterate any hope of such conversations for only five weeks.

When Jagmeet Singh pretends there are enough billionaires in Canada to pay for the NDP’s platform, he’s living in the campaign world. When Erin O’Toole defends freedom of choice on vaccinations while everybody who actually has to govern—Doug Ford, Joe Biden, Jason Kenney, Scott Moe—is implementing tough vaccine mandates, he’s living in the campaign world. When Chrystia Freeland brags in one sentence about all the vaccines her government has bought, using money, then says she stays up at night worrying about private sector encroachment on the health-care system, she’s living in the campaign world.

And lately what’s worse is that campaigns don’t just delay the serious work while they’re happening: they discourage serious work while they’re looming. And campaigns never stop looming.

Here’s what will be happening around Trudeau in the wake of his latest victory. There will be urgent meetings and memos whose theme is that the next election campaign—the battle for 2022; 2023 at the outside—is already underway. Every decision must be taken with an eye toward highlighting contrasts from the last campaign. There’ll have to be a Minister for Assault Weapons Elimination. The health minister will have to become the Minister for Public Health Sanctity.

READ: Old man Trudeau enters an election year as the veteran politician

The Liberals were in pre-election mode in 2018, after all, when they pressured Jody Wilson-Raybould to cut a novel out-of-court deal for SNC-Lavalin. Various aides and emissaries from the PMO and the finance minister’s office tried to explain it all to her. How there was a provincial election coming in Quebec. How a federal election would follow the year after. How decisions of law and order needed to be made with a sensitive eye to the federal and provincial parties’ fortunes. The procession of aides and emissaries making electoral arguments to the attorney general, in her capacity as an official of the judiciary, on government time, saw no contradiction in any of this: in modern politics, the government and judiciary bend to the party. The aides and emissaries must have been amazed that they even needed to explain any of this.

The Liberals were in pre-election mode in 2020, less than a year after exiting election mode, when Trudeau and others started using words like “opportunity” to describe a global health catastrophe. “As much as this pandemic is an unexpected challenge, it is also an unprecedented opportunity,” the Prime Minister said after he fired his finance minister.

Then, for five weeks over the summer, the Liberals shifted briefly from pre-election mode to election mode. Now they are back in pre-election mode. This car only has two speeds.

The PM will keep his senior staff intact if he can. Now’s no time to shake things up! An election’s coming! Anyone who does leave will be replaced from within by people who grew up in the system Trudeau built and who will perpetuate it because they can’t imagine another way of governing. Trusted emissaries of the PMO team will be assigned as chiefs of staff to look out for cabinet ministers, who cannot be trusted to make decisions or listen to complicated representations from the outside world, because there’s an election coming.

The spring budget from Chrystia Freeland and Michael Sabia, a new finance minister and a new deputy minister, announced more than 200 new programs and initiatives. The Liberal platform had 182 chapter headings. All of this was simply layered over the residue of countless hundreds of earlier strategies, pilot projects and proofs-of-concept, like a new deposit of sediment dumped onto a bed of shale. Somebody will be put in charge of lining up the new plans with the nearly new plans and coming up with even newer plans for a Fall Economic Update that has to test well with focus groups because, you see, there’s an election coming.

The Liberal platform did make one reference to “a comprehensive strategic policy review of government programs.” This “continuous process” is supposed to “examine how effectively each major program and policy is doing in meeting the biggest challenges of our time.” That would be such a good idea. There is no chance it will happen. Who has the time? Who on earth would be granted the serenity to judge government effort on its results, instead of on its marketing potential? The promise of a continuing effectiveness review is best understood as a forlorn hope, a message in the bottle. Someday whoever wrote that line will be able to say, “Look, I tried. But there was no time. An election was coming.”

Meanwhile the Conservatives will be quietly discussing the trade-offs between the market and deft intervention that might one day bring Canada a less cumbersome government that ensures prosperity while interfering less in citizens’ lives. Just kidding! No, the Conservatives will be trading insults on Twitter as various factions circle the wary camper Erin O’Toole like wolves, bickering over whether they should start snacking now or later. There’s an election coming, you see, and—well, from here it becomes a bit of a choose-your-own adventure. Only O’Toole, battle-hardened from his first fight, can apply lessons to the next one. Or only O’Toole could have screwed the last one up, so turf him and get a new leader. Pick one! Make fun of the people who pick the other!

None of these is really a question about governing. They’re all questions about getting a chance to govern. The gap between the two notions is the place where good policy goes to die.

It’s fun to rant, but am I describing a problem that has a solution? “Modern campaign imperatives limit the space available for thoughtful governance” is a fun sentence, but what’s the remedy?

I’m forced to admit it would probably be wrong to stop having elections, although lately it’s become easier to understand the temptation. And Canada’s decade-long flirtation with “fixed election dates” at the national level has ended where it was always going to end: with fixed election dates in addition to bonus optional election dates. Fixed election dates were supposed to take the pressure off governments and oppositions by ensuring everyone knew they could count on plenty of time between votes. No such luck.

Perhaps, though, it’s time to consider two modest reforms. One would take some of the competitive pressure off political parties between elections. The other would dissuade overheated rhetoric during campaigns.

First, it’s time to bring back public funding for political parties. Parties used to receive a government subsidy proportional to their share of popular vote, so that the more votes you earned, the more money you’d have to fight the next election. Stephen Harper’s government eliminated that system in 2011. And to be fair, it’s not a great system. It perpetuates incumbent advantage, providing big war chests to parties that already had big war chests, crowding out newcomers.

But the alternative—individual donations, capped at a low annual total, as the only financing mechanism for parties—forces parties to spend most of their time asking their supporters for money. Long experience has shown that the most effective way to get somebody to give your party money is to make them scared or angry. So now we have a system that requires every party to spend much of its time frightening or enraging the largest possible number of Canadians. It becomes a hard habit to break.

Instead of per-vote subsidies, maybe implement a flat subsidy to political parties, with some threshold for eligibility so fringe or fly-by-night parties wouldn’t automatically qualify. Individual donations would still be permitted, but they needn’t remain the only source of income for parties. Peddling outrage shouldn’t be the only way to finance the operations of parties that aspire to government.

My second proposed reform is even simpler. Party leaders’ debates during campaigns should be organized so that no leader has less than three minutes to answer any question.

The most ridiculous thing about the televised debates in 2021 wasn’t a loaded question for the Bloc Québécois leader, it was the ridiculously short time limits for answering. Leaders were cut off before they could complete a sentence. And frankly, some of the leaders were probably delighted. It’s easy to bark out some haiku about “more justice! Less waste!” Or whatever. Harder to compose a few sentences—even three minutes is only 300 to 390 words for most speakers—that reveal something about how a leader has thought about an issue. Or whether they have.

It’s easy to guess why our TV debates have ridiculously short time limits: because they’re designed by TV producers, who like it when debates produce a maximum of heat and a minimum of light. But if we’re going to at least pretend that elections are about more than great TV, then we should follow through on our convictions by presenting at least one event during every campaign that requires leaders to be thoughtful.

Of course, neither of these reforms has any chance of being implemented. They’d have the effect of reducing the pressure and the breakneck tempo of partisan activity at the federal level in Canada. They’d give thoughtful people more time to be thoughtful, and governments more time to concentrate on governing. But if you want to know the truth, most of our politicians really like high-stakes campaigns. Growing up, they dreamed of acceptance speeches, not of meeting with stakeholders to design a workable new program. There’s something intoxicating about the campaign trail. It calls to our leaders even now. They won’t resist its song for long.

This article appears in print in the November 2021 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “The triumph of Justin Trudeau.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.