Kenney’s won the Tory crown. Now he needs to keep winning.

Jason Kenney takes hold of the Progressive Conservatives. Next on his to-do list: merge with another party.

Jason Kenney celebrates his leadership win at the Alberta PC Party leadership convention in Calgary, Alta., Saturday, March 18, 2017. (Jeff McIntosh/CP)

Share

Jason Kenney stood on the convention stage with his two Alberta Tory leadership rivals to await the results of the delegate vote — not so much to learn who won as to learn the margin of victory. As the party president went through the formalities at the microphone before the “moment you’ve all been waiting for” moment, Kenney took his victory speech out of his jacket pocket, gripping its folded edges. One can hardly blame him for being confident on this one — his win with 75.4 per cent of the vote was at or even below where some operatives were expecting. Perhaps we should allow him to savour the predictability of this result. The next several steps will come with far, far less certainty.

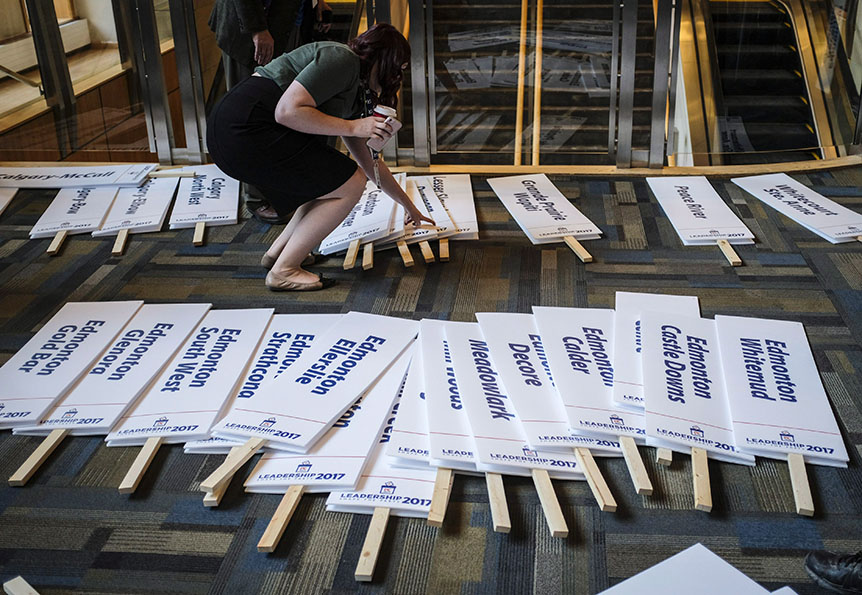

The path to power Kenney has chosen for himself in Alberta involves an inordinate amount of time behind debate lecterns and awaiting results in halls with a cash bar and anxious partisans. Kenney organizers were surprised how easy this first one was, to formally take over on Saturday a Progressive Conservative party that won 12 straight Alberta elections then shambled into a third-place centre-right rump — too small and demoralized a remnant group to prevent Kenney’s declared plan to dismantle the party and fuse it with the now-larger Wildrose party and create some new Frankenservative beast to crush the Rachel Notley NDP in 2019.

FROM THE ARCHIVES: Jason Kenney on life after Ottawa and uniting Alberta’s right

It’s all those other steps that should prove far trickier for Kenney, greater tests of his political skills than a leadership race against thinly organized candidates. He now has to (a) overhaul the PC party constitution to allow the party’s dissolution and hold a successful membership referendum to take Ol’ Tory behind the woodshed and shoot it; (b) persuade the Wildrose party to do the same; (c) negotiate the creation this conservative party, united by hatred of carbon taxes and New Democrats, and other policies TBD; (d) mount another leadership bid and win new that party’s crown; and (e) take your new party to the voting masses in two years.

In normal politics, a candidate appeals to partisans and wins a leadership, then must pivot politically to appeal to the general public. Kenney now must perform the above sequence of pivots to court different audiences, most notably reaching farther to the right to woo staunchly conservative Wildrosers into a merger and then win that second conservative party primary. Following that rightward reach he must twist back to persuade everybody else in the province he should be premier. It’s well known how tireless Kenney was as a federal cabinet minister and Harper point man for newcomer communities, and then hustling since July throughout Alberta to secure Tory delegates. Now we get to see how agile the 48-year-old is.

He’ll doubtless alienate people at every step, and his success will be measured in how minimal those damages are. Some will abandon the PCs now — one common button at this weekend’s convention said “Keep the P in PC” — but now we know this will only be some portion of one-quarter of the party, and many of those Red Tories will play the pragmatist for now. Katherine O’Neill, the party’s avowedly centrist president, vows to stay on under Kenney’s leadership, and says this unity talk has already reestablished communication lines with the Wildrosers who long ago abandoned the Tories: “We’re getting used to knowing each other again,” she says. The party board meets its would-be dismantler Kenney on Sunday. O’Neill says she doesn’t expect a mass resignation, which means she expects a smaller one.

Courting the Wildrose party should be the bigger challenge. They already lead the NDP comfortably in the polls; they don’t necessarily need a coalition to win, but leader Brian Jean has always wish for a dancing partner in the Tories. (He meets with Kenney on Monday, the first of likely several sitdowns.) Kenney didn’t need 75 per cent of the vote on the Tory leadership’s first ballot, but that’s the necessary threshold for the Wildrose to dissolve. Insiders suggest terms could include some avowed conservative positions that scare off more centrists, and a bunch of populist pledges to not have a centralizing leader. Many Wildrosers fancy themselves more of a movement than a party, and the past leaders have struggled to tame the grassroots. Stephen Harper managed to consolidate power when he merged the Canadian Alliance to the federal Tories a decade ago, but in some ways the Wildrose represents the more ragged Reform Party, an organization that leaders struggled to move to more moderate ground.

If all that works out, a leadership race will pit Jean against Kenney and likely a few other people. Kenney didn’t have to bother pledging much policy to win the Tory race — unity and promising to scrap the Alberta carbon tax were plenty sufficient — but a Conservative Party of Alberta’s members will demand more red meat. This stands to play into Notley’s hands, as her NDP is already structuring government policy around the image of an NDP protecting Albertans and their beloved public services from the scourge of an evil cast of Kenneyite slashers that will flood every emergency ward and teachers’ break room with pink slips.

The public seems hungry for an end to Alberta’s NDP experiment, but through all these pivots Kenney must prove he’s that man. His image as a right-wing champion is well-known, and even some Red Tories view Brian Jean as the more moderate and palatable option. Polls show that he’s more popular than Kenney, as well.

Underlying that is a problem with Kenney’s first major pivot, the one he took last year by leaving Parliament to enter provincial politics. Janet Brown, a Calgary pollster, recently held a focus group with apolitical Albertans; Kenney wasn’t the topic, but he came up in the conversations. She asked about their impression of him: not so great. “They have trouble saying anything nice about him, except that he has federal experience,” Brown says. That was also his biggest liability among this panel. “One guy in the focus group said we don’t like it when people from Ottawa tell him what to do in Alberta.”

Sure, Brian Jean also came to Alberta after a decade as a Conservative MP, but he’s now at a couple years in the legislature, and he was too low-profile in Parliament for people to really know that about him — unlike Kenney, Harper’s de facto Number 2.

As much as he roars around the province in a Dodge pickup, he bounds out of it in a navy blazer. As much as he looks comfortable in a cowboy hat and talks about hard-working Albertans who shower after their day shift not before, he quotes St. Augustine of Hippo in speeches and has referred to price bloat on “hydro” bills — a true tell of an outsider, as Alberta doesn’t rely on hydroelectricity.

The late Jim Prentice tried returning from Ottawa and his bank executive job, and then finagling a collapse of the Wildrose under his expanded tent. The end result was NDP government. Kenney wants to undo that government. Leaving central Canada behind and winning the Tory crown were, let’s recall, the easiest steps for Prentice, too.