Online hate speech in Canada is up 600 percent. What can be done?

Countries across the world are grappling with online hate speech through legislation. Is Canada about to join them?

Marchers at a white-supremacy rally encircle counter protestors at the base of a statue of Thomas Jefferson after marching through the University of Virginia campus with torches in Charlottesville, Va., USA on August 11, 2017. (Shay Horse/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Share

This piece originally appeared at The Conversation

Under Hitler, Germany experienced the consequences of a nation caving in to propaganda and hate speech. This may explain its government’s urgency to enact a new law, known as the “Facebook Act,” in response to the recent alarming rise of hate speech online.

Canada is experiencing a similar rise.

Media marketing company Cision documented a six-fold rise — that’s a 600 per cent increase — in the amount of intolerant and hate speech in social media postings by Canadians between November 2015 and November 2016. Hashtags such as #banmuslims, #siegheil, #whitegenocide and #whitepower were widely used on popular social media platforms such as Twitter.

Some analysts blame Trump. But Canadian media outlets shouldn’t be too smug about their adherence to the practice of fair and balanced journalism.

A group of scholars at Ryerson University conducted a critical analysis of how the Canadian media covered the resettlement of Syrian refugees in Canada between September 2015 and April 2016. They found several news outlets played a major role in reinforcing the negative image of Syrian refugees and Muslims in the public eye.

The refugees were subject to “othering,” the practice of depicting nonwhite cultures as “alien,” and highlighting differences rather than shared values or interests. The new arrivals from Syria were stereotyped, criminalized (especially men) and perceived as passive, lacking agency, vulnerable, needy and a drain on government resources. Male Syrian refugees were viewed as security threats and female Syrian refugees as voiceless, oppressed and desperate.

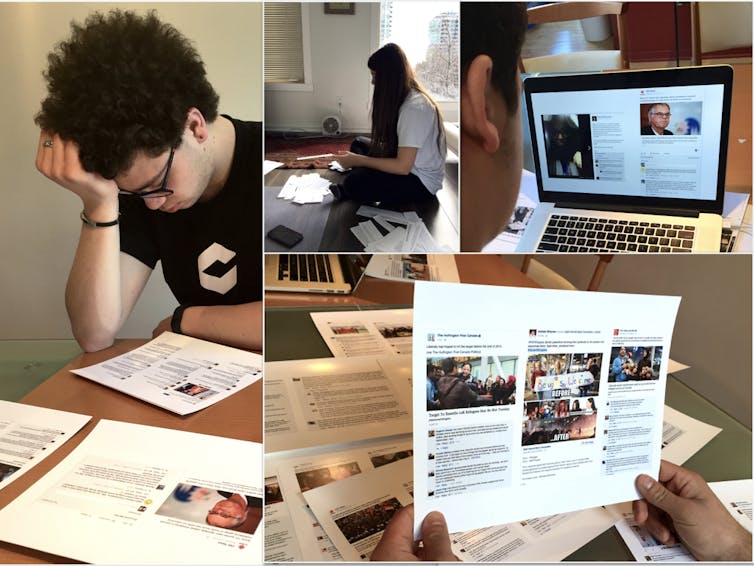

My research study investigates the way youth view their role in society as it relates to refugees, and how they regard and interpret online propaganda.

The $74 million question

The European Commission recently announced a new set of guidelines and principles for online platforms to prevent content inciting hatred, violence and terrorism, and Twitter began implementing its new rules for fighting hate on Nov. 1.

(AP Photo/J. David Ake)

Should Canada follow in Germany’s footsteps and enact a law that would pressure social networks to remove offensive posts within 24 hours or risk fines of up to $74 million for failing to comply?

Adopting new regulations forcing social media platforms to respond swiftly could be an effective intervention to halt the spread of hate speech online. However, it could also prove to be challenging, as moderators wade into complex language and often get it wrong. Ultimately, we need to adopt a systematic response to hateful and dangerous rhetoric online.

The German social media law has been the subject of criticism since it was announced. Some critics say the law is too broad while others warn it could be the executioner of free speech. The thin line between hate speech and free speech is the focus of many concerned Canadians.

In Canada, hate speech is addressed in the recently updated Criminal Code (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46). However, the applicability of this law to online hate speech is a frequent subject of debate that produces conflicting conclusions. In particular, the Defenses section of the code outlines cases where the proponents of hate speech could be exempted.

Distinguishing hate speech from fear speech — speech originating from fear and masked with terms and expressions usually associated with hate — is by itself a great challenge. Motion 103 (M-103), which condemns Islamophobia in Canada, and was passed in the House of Commons this Spring, is perceived by some Canadians to be suppressing free speech.

How to stop hate online?

Extremist parties, politicians and their fans have all successfully taken advantage of social media platforms to spread messages filled with racism and intolerance — even incitement to radical views.

Right-wing activists and the movements they espouse now total more than 100 organized groups in Canada. They are more visible and also better connected than ever before.

Stopping hate speech and extremist views on social media may be an impossible mission.

Yet, a majority of Canadians get their news about politics through social media giants such as Facebook. Facebook says 84 per cent of young Canadians actively use the social media platform.

(AP Photo/Noah Berger)

“The essence of propaganda consists in winning people over to an idea so sincerely, so vitally, that in the end they succumb to it utterly and can never escape from it,” said Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s minister of propaganda and national enlightenment.

According to the Shannon and Weaver Model of Communication, created in 1948 by mathematician and electronic engineer Claude Elwood Shannon and scientist Warren Weaver, every communication includes an information source, a message, a transmitter, a receiver, a destination and a noise source.

If we apply the communication model to online hate speech, we can identify the information sources as the propagandists, including extremist parties. They craft a simple, direct message such as “Muslims are terrorists” and transmit it through social media posts.

The destination is the audience the propagandists are focused on manipulating. This audience belongs to a whole spectrum, ranging from supporters of the idea to an audience that is outraged by it.

The receiver is the system used by the audience to decode the message and interpret it. The noise source includes the laws, acts, filtering and flagging strategies put in place to prevent the message from reaching the destination.

So far, it has been proven that the sender of hate speech is unstoppable and the noise source lacks efficiency, since hate speech not only persists but also is on the rise.

Therefore, we must shift our tactics. We could for example, focus on the receiver and the destination of the hate-filled message. We could teach the audience — youth in particular — how to withstand digital hate speech propaganda.

Youth need to be part of the solution

Conversations that characterize millennials as passive consumers of news with little and incidental exposure to world events could not be more wrong. A study conducted by the Media Insight Project in 2015 found youth between the age of 18 and 24 are “anything but ‘newsless,’ ” passive or uninterested in civic issues.

Instead, they consume news and information in strikingly different ways than previous generations and their paths “to discovery are more nuanced and varied than some may have imagined.” Social media plays a large role in their news consumption.

Many youth are critical of media content and their choice of the information and the news they read online is far from random. They often see or experience direct or indirect racial discrimination online or witness unproductive, uncivil or disturbing Facebook discussions.

They recognize the agendas and algorithms behind the posts that pop up on their walls, and they hunger for an influential voice that would disrupt the discourses about issues that affect their lives.

Yet, fearing a backlash, a majority of youth choose to remain bystanders in an era where their social media presence and skills are needed the most. They remain “power users (frequent users),” instead of “powerful users (influential users).”

(AP Photo/Ted S. Warren)

Hate speech and ugly online conversations around Syrian refugees are mainly orchestrated to spread fear among people who might otherwise be members of actual or prospective welcoming communities. A campaign to counter propaganda, led by agents of change, is important to counterbalance the negative influence and allow host societies to make informed choices.

Youth could be our best candidates to be these agents of change, given their familiarity with social media. For this to happen, young people need to develop civic online reasoning and identify ways to leverage the power of social media for “greater control, voice and influence over issues that matter most in their lives.”

They need to understand where their political tolerance and intolerance comes from, and understand the concerns, emotions and values that generate public attitudes.

Many argue that education is not enough. However, equipping and empowering youth to disrupt the messaging transmitted by radical extremists or parties with racist agendas starts with the pedagogy of understanding oneself.

The power of self-knowledge

My research study involved 126 in-depth interviews with 42 youth between 18 and 24 years old from Canada, the U.K., France, Belgium, Germany, Portugal, Italy, Poland, Greece and Lebanon. During the interviews, I engaged these young participants in the process of learning about themselves using tools I adapted from Personal Construct Psychology.

I wanted to understand how they viewed their role in the integration and inclusion of refugees in their societies, in a context where the image of refugees was deeply influenced by social media, especially after terror attacks.

I also wanted to discover what knowledge and skills they developed through the process of understanding themselves by identifying their construct systems — the “lenses” they used when decoding digital propaganda targeting sensitive and controversial issues such as the Syrian refugee crisis.

Through our discussions, each of these 42 young people had an “aha moment.”

Regardless of their geographical locations or the ways they experienced the refugee crisis and the recent terror attacks, they had the same sudden realization. Not only could they control how social media influenced them, but they also had a role to play in shaping the image of refugees through what they shared online.

They became critical of media content. They developed empathy towards both refugees and people who rejected newcomers. They moved from passive bystanders, to became confident agents of change, ready to play a leadership role in counterbalancing the digital hate speech propaganda against refugees.

To eradicate digital hate speech propaganda, we need to prevent propagandists from reaching their objectives.

Laws such as Germany’s “Facebook Act” constitute one piece of the solution. The other key is to make sure audiences are trained to better withstand manipulation.

Our youth, once equipped and empowered, are our best candidates to disrupt the messages spread by propagandists and to pursue the mission of putting a stop to hate speech.

Nadia Naffi, Full-Time Faculty in the Education Department, PhD Candidate in Educational Technology & Public Scholar, Concordia University

This piece originally appeared at ![]()

![]()