338Canada: A tale of two premiers

Philippe J. Fournier: A few years ago, Francois Legault and Jason Kenney were making history. Today, only one of them is sure to survive their next election.

Legault chairs a premiers news conference as premiers John Horgan, Kenney, and Scott Moe appear onscreen, on March 4, 2021 in Montreal (Ryan Remiorz/CP)

Share

When Jason Kenney lead his brand new United Conservative Party to a decisive majority victory in April 2019, some observers (yours truly included) wondered whether Alberta had just entered a new era of political dynasty. It wasn’t a far-fetched scenario: Even by earning more votes in absolute numbers in 2019 than in 2015, Rachel Notley’s NDP went for a majority at the Alberta legislature to the opposition benches with only 24 seats (almost entirely from urban Alberta). With the benefit of hindsight, it now appears obvious that the NDP simply did not stand a chance of winning the 2019 election against a single, united conservative opponent.

Mere months later, Andrew Scheer’s CPC won a stunning 69 per cent of the vote in Alberta in the 2019 federal election. It therefore appeared like an obvious understatement to say that Alberta conservatives had fully regained control of the political landscape of the province, and perhaps this new right-of-centre creature lead by Jason Kenney could potentially dominate the province for years to come.

In Quebec, François Legault’s Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) had, just six months prior, broken a half-century cycle in Quebec politics by winning a majority at the National Assembly, inflicting both the Quebec Liberals and Parti Québécois the worst defeats in their history. Legault, himself a former prominent PQ MNA, lead his party to victory by taking the middle road between two foes still deeply committed to fighting “La question nationale”, which, polls have indicted, many Quebecers feel is yesterday’s battle.

Legault’s victory in 2018 culminated a decade of high political volatility in Quebec. Three straight provincial elections featuring the same three parties had resulted in three different winners (PQ in 2012, Liberals in 2014, and CAQ in 2018). On the federal front, Quebec voters had overwhelmingly supported Gilles Duceppe’s Bloc Québécois in the 2008 federal election, only to turn massively towards Jack Layton’s NDP in 2011, and then elected 40 MPs from Justin Trudeau’s Liberals in 2015.

Yet, with only six months before Quebec voters go to the polls (the Quebec general election is scheduled for Oct. 3, 2022), Legault’s position is, according to recent polling, more comfortable than any sitting Quebec premier since Robert Bourassa in 1989.

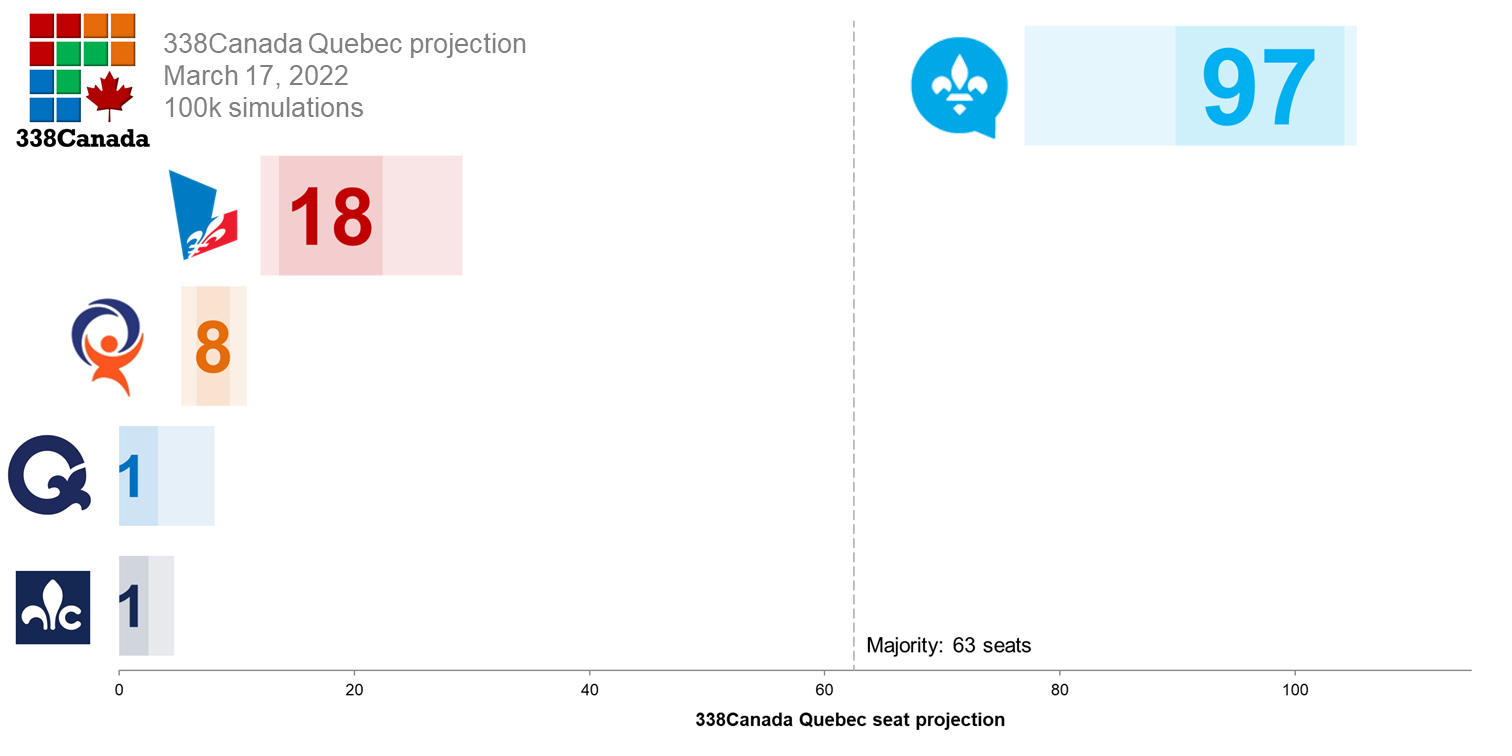

To wit: The latest 338Canada projection in Quebec gives the CAQ the edge in 97 of the province’s 125 electoral districts, a total well above the 63-seat threshold for a majority at the National Assembly. Unless the CAQ performs a nosedive of historic proportion in the coming months, Legault should handily win a second straight majority this fall.

The CAQ domination is such that most storylines about the Quebec election revolve around which party shall occupy the opposition benches, and which could even be virtually wiped off the Quebec map. The Quebec Liberals still rely on many safe Montreal seats where most non-francophone voters live and have historically been reliable Liberal supporters, but even this support may be dwindling. The latest Léger poll has the Liberals in fifth place among francophone voters, and measures a softening of non-francophone support for the Liberals.

The same Léger poll had Quebec Liberal leader Dominique Anglade as the favourite candidate for premier by 9 per cent of respondents—including a measly 4 per cent among francophone voters. Whatever Anglade is selling, most Quebecers aren’t buying, even several traditionally reliable Liberal voters. This only adds to Legault’s apparent aura of invincibility.

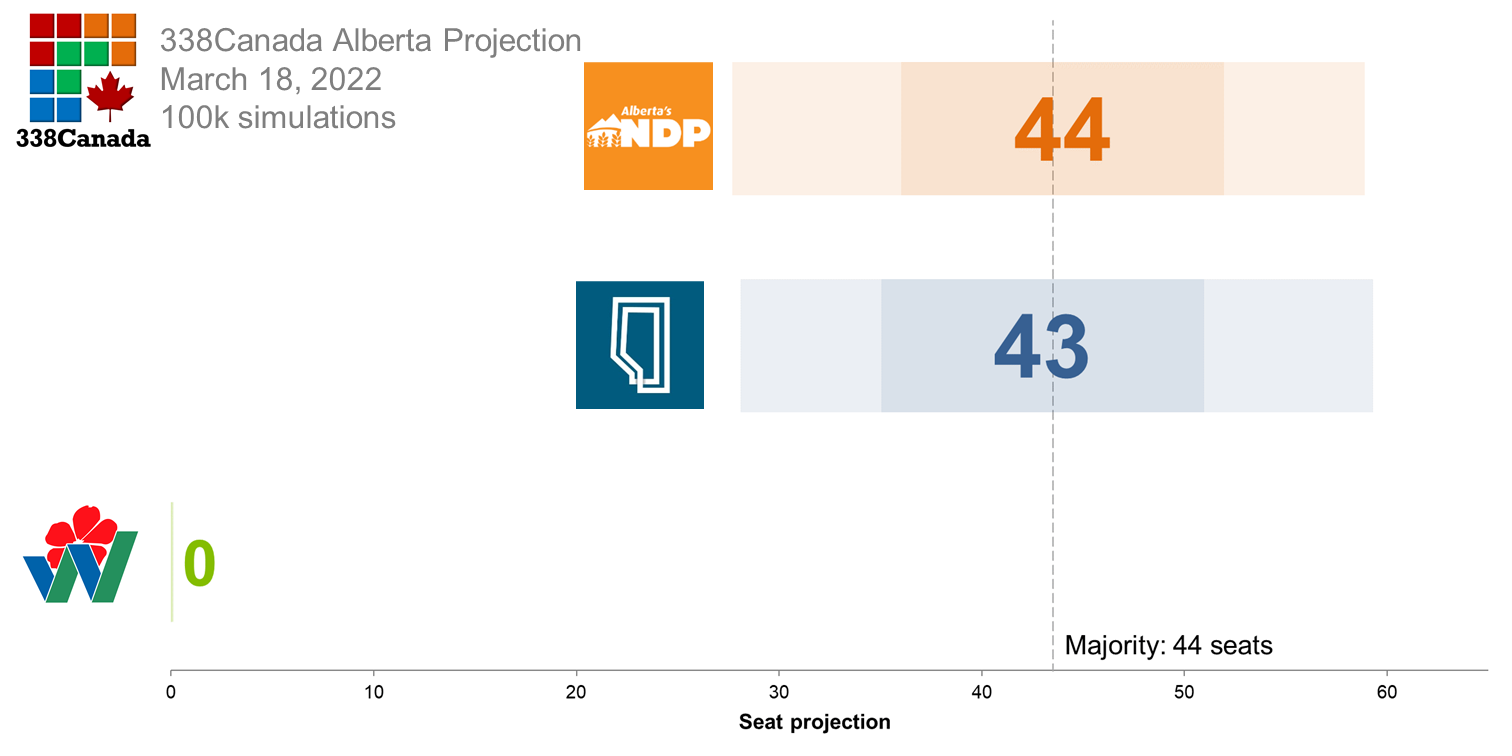

The contrast with Jason Kenney and the UCP could hardly be starker. Not only has the Alberta premier accumulated a long string of poor approval numbers since the pandemic reached our shores in the spring of 2020, the UCP has trailed the NDP in voting intentions in virtually all publicly released polls since December 2020 (a private poll from Janet Brown Opinion Research leaked by the UCP last week showed a modest rebound for the UCP). Moreover, the latest round of premier approvals by the Angus Reid Institute has Kenney at 30 per cent approval among Alberta voters, second last of the list of Premiers in Canada (only Manitoba’s new Premier Heather Stefanson fared worse than Kenney).

Using the available data, the 338Canada Alberta model measures the NDP and UCP in a dead heat in the seat projection: 44 seats for the NDP and 43 for the UCP, both numbers bearing wide confidence intervals. If an election was held this week, the projection would have been the very definition of a toss up between the main parties:

Former Wildrose leader Brian Jean’s comfortable victory in the Fort McMurray-Lac La Biche by-election last week only muddies the water further for Kenney. While Jean’s by-election win was not a surprise, his clearly stated objective of unseating Kenney at the UCP convention in Red Deer next months adds to the unfolding drama. Party organizers expect more than 10,000 UCP members to show up and vote on Kenney’s leadership, so not only do we wonder whether Kenney could beat Notley in a general election rematch, but it looks far from certain whether Kenney will manage to dodge this friendly fire and get to lead his party.

Contrast this with the Marie-Victorin by-election taking place in Quebec on April 11, where neophyte CAQ candidate Shirley Dorismond, a former nurse and union leader, has had to backtrack on several comments critical of Legault’s CAQ that she made before running for the CAQ. Dorismond had been especially outspoken on systemic racism, which the CAQ does not recognize exists in Quebec. As union leader, she butted heads with the CAQ government on union negotiation on several occasions. Despite all this, Dorismond was all smiles when she was introduced by Legault last month and promised “to be part of the solution.”

We are witnessing a fascinating tale of two Premiers: While Legault was elected in a period of political chaos and tumult in Quebec, he has so far succeeded in calming the storm, and even convinced former foes to kiss his ring. Meanwhile, Kenney’s UCP victory in 2019 had the air of a return to conservative hegemony in Alberta, but is now forced to welcome a new MLA in his caucus who won his seat largely by publicly saying he will work to boot the premier out of office.