A bad trip: Legalizing pot is about race

We know Aboriginal and black people are overrepresented in prisons for drug charges, but it’s time for a clearer picture of just how bad the situation is

The Liberal government’s point man on pot says Canada Day 2018 should not be about legalizing marijuana but about recognizing the country’s history. Liberal MP Bill Blair responds during Question Period in the House of Commons on Parliament Hill, in Ottawain a February 25, 2016, file photo. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Adrian Wyld

Share

Since 1908, when the Canadian government passed the Opium Act prohibiting the “importation, manufacture and sale of opium for other than medicinal purposes,” race has been a key aspect of Canada’s drug laws. It was impossible to separate the government’s thinly developed health concerns about opium from its much more deeply developed racist views on Chinese immigrants. Banning opium then was a part of the larger, shameful goal of preventing Chinese immigration. Fast-forward to 2017 and the Liberal government’s new Cannabis Act, which will legalize the recreational use of marijuana. Amidst the debate about production, distribution and criminalization, one dirty little secret remains: this is still about race.

“One of the great injustices in this country is the disparity and the disproportionality of the enforcement of these laws and the impact it has on minority communities, Aboriginal communities and those in our most vulnerable neighbourhoods,” said Bill Blair, the parliamentary secretary to the minister of justice said back in February of 2016. It was an astonishing admission. In outlining the rationale behind the government’s legalization plans, Blair made race a central issue. For a former police chief to suggest that minority groups have been unfairly hit by Canada’s pot laws was startling to some, and a long overdue admission to others. Has the criminalization of pot really masked a race issue that the legalization act will now fix? If Blair is right, the new act will, among other things, expose a nasty social injustice and deeply troubling issue for police. The trouble is, there is no systemic data available to support his claim.

READ MORE: Bill Blair: The former top cop in charge of Canada’s pot file

I asked the minister of justice’s office to send me the statistics that supported Blair’s claim and got nothing in return. “Not going to be a lot of help to you on this one,” said David Taylor, the spokesperson for the minister. He asked around to see if any other department had an answer and found nothing. “What I am being told is that stats on race and ethnicity are not tracked at the police or court level, so we cannot determine whether or not Indigenous or black people have higher conviction rates due to cannabis,” he said. That’s odd, since Blair said the exact opposite. For a government that touts its commitment to evidence-based policy, where did his claim come from?

There is not one source, but a few reports suggest Blair is right. In 2013, Howard Sapers, then Canada’s federal correctional investigator, tabled a report on ethnicity in Canada’s prison system that revealed troubling data. “Over the past 10 years, the Aboriginal incarcerated population increased by 46.4 per cent while visible minority groups (e.g. Black, Asian, Hispanic) increased by almost 75 per cent,” he wrote. “During this same time period, the population of Caucasian inmates actually declined by 3 per cent.” As Sapers discovered, black and Aboriginal people in Canada are disproportionately represented in federal jails: “9.5 per cent of federal inmates today are Black (an increase of 80 per cent since 2003/04), yet Black Canadians account for less than 3 per cent of the total Canadian population. Aboriginal people represent a staggering 23 per cent of federal inmates yet comprise 4.3 per cent of the total Canadian population.” Sapers openly questioned the fairness of our justice system.

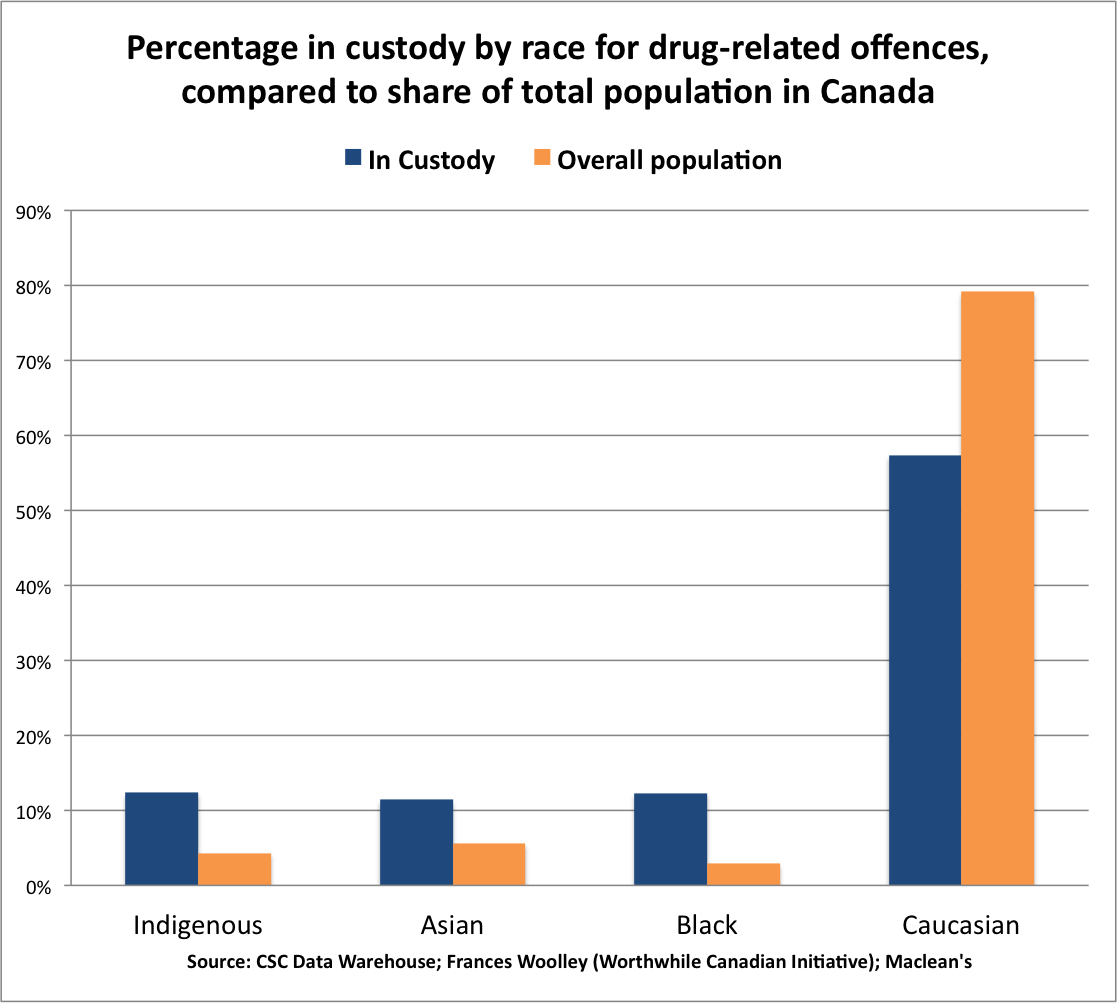

While that report opened a window on the race issue, it didn’t focus on drug arrests or specifically on cannabis. I went to the public safety minister to get more data on this, and his office simply sent me back to Justice. I was running in circles. Finally, after three days of asking, Correctional Services Canada sent me some data on the number of drug-related arrests as they correlate to race. In 2014, there were 2,177 inmates in federal prison for drug related reasons (Schedule 2). Close to 270 of those were black. About the same number were Indigenous. While the vast majority was Caucasian, 1,360, it still represents a significant overrepresentation of black and Aboriginal people relative to their share of the general population.

These stats are revealing but still not specific about what kind of drug is at play. ”Canada does not collect this kind of data,” Neil Boyd, a professor at Simon Fraser University’s School of Criminology told me. “It’s fair to say that Indigenous Canadians are overrepresented with respect to almost all criminal arrests, convictions and sentences to imprisonment. Legalization of cannabis would, then, have a disproportionate impact on Indigenous Canadians.” But even he can’t say for sure by how much.

READ MORE: Scowly Liberals legalize the demon weed

There have been other reports that fill some gaps. The results of the recent Traffic Stop Race Data Collection Project in Ottawa, in which a York University research team analyzed 81,902 traffic stops over a two-year period between 2013 and 2015, found that Black and Middle Eastern-looking people were stopped two to three times more frequently than Caucasian drivers. The police association argued this did not prove racial profiling, but it was hard to see it another way.

In 2002, the Toronto Star conducted its own analysis on the difference between how blacks and whites were treated by police regarding basic drug charges and they found a wide ranging disparity. “Black people, charged with simple drug possession, are taken to police stations more often than whites facing the same charge,” the Star found after using data from previously unseen police databases of more than 480,000 incidents. “Once at the station, accused blacks are held overnight, for a bail hearing, at twice the rate of whites.” The Star showed what many in the black community already felt: they were being unfairly targeted. “

The police usually deny there is any racial profiling in Canada, despite Bill Blair’s statement. Sen. Vern White, the former Ottawa Police chief, told me he doesn’t buy the argument that race has any impact on arrest rates for pot. “I don’t remember arresting anyone for simple possession of pot for 25 years,” he said. “It usually comes with another charge, like trafficking. The reason is simple: paperwork. If you charge someone for simple possession you have to fill out a complicated form so no one bothers unless there are other charges. It is too expensive. As for charging non-white versus white, stats will tell us that Aboriginals have the highest arrest and incarceration rates, but I never saw marijuana as the reason for that,” White said.

READ MORE: How public officials got into the weed game

White’s argument doesn’t hold for people like Kate Kasper, a lawyer at Aboriginal Legal Services in Toronto, who works on the front lines of this issue. “Do I think that there is a strong correlation between drug arrests, convictions and race?” she asks. “Absolutely. Unfortunately, the numbers to support this remain elusive. There are gaps of information that occur from beginning to end in the criminal justice system that—if filled—would provide a much clearer picture as to how race factors into conviction rates. To begin with is the lack of race-based aggregate data collection from police agencies across the board. As we move through the justice system, the various court houses do not track conviction rates for offences as specific as the possession of marijuana and certainly, do not mark or identify the race of the offender either entering the plea or being found guilty at trial.”

Is the lack of data merely demonstrating logical and understandable sensitivity to minorities? After all, no group wants to be targeted for profiling purposes. Not for Akwasi Owusu-Bempah, an assistant professor at the University of Toronto’s Department of Sociology, who believes the lack of data is no accident. “Our criminal justice system and various levels of government systematically suppress race-based criminal justice data,” he says. Owusu-Bempah argues that police don’t want the public to know that “Black, Brown and Aboriginal Canadians have been disproportionately harmed by Canada’s war on drugs and by cannabis prohibition in particular. Cannabis is a gateway drug,” he says. “But not in the way that people typically think of it. Cannabis has been used by the state as a gateway into the lives of societies most marginalized populations.” In other words, once someone is arrested for pot possession, Owusu-Bempah believes it begins a cascading descent into Canada’s justice system, which is why Blair’s declaration of the great pot injustice struck Owusu-Bempah as hypocritical.

“Blair has profited from this twice—once as the criminalizer (police officer) and once as the drug czar,” he says. “What gets me about that is that he has argued pardons are off the table for those previously convicted.” That is a key point. If Blair believes that too many people have been unfairly convicted by old pot laws, why won’t the government consider pardoning those already convicted? The Liberals will have to deal with this issue in the next year as both the NDP and some Conservatives argue for immediate decriminalization.

The legalization of pot still has many hurdles to overcome. Provinces will struggle to set up proper retail and licensing systems by July 2018. But one thing this whole process should do is to force governments at all levels to find a way to overcome the legitimate political sensitivities around race data collection and find a responsible, systemic way to aggregate racial and ethnic data in order to get a less opaque view of the criminal justice system and of drug enforcement. “It is my hope that we will see more racial equality as a result of the change in legislation, but that will not come naturally,” Owusi-Bempah says. “In order to reduce racial disparities in drug arrests, a conscious effort will have to be put forth on the part of legislators, policy makers and practitioners, police, crown and judges.”