Calm in the storm: The rise and rise of Ahmed Hussen

He arrived in Canada as a teenage refugee from Somalia. With ‘preternatural calm,’ Ahmed Hussen is now Canada’s immigration minister.

Ahmed Hussen, who was just elected to the House of Commons for York South-Weston, sits in his campaign office on Lawrence Avenue. (Melissa Renwick/Toronto Star/Getty Images)

Share

It was the second week of the Trump administration, and the second consecutive Sunday the Prime Minister’s staff spent grinding it out in the office. President Donald Trump’s travel ban on seven Muslim-majority countries had just taken effect, stranding hundreds at airports, held back by customs officials who barely understood their marching orders. Furious protesters flocked to airports by the thousands.

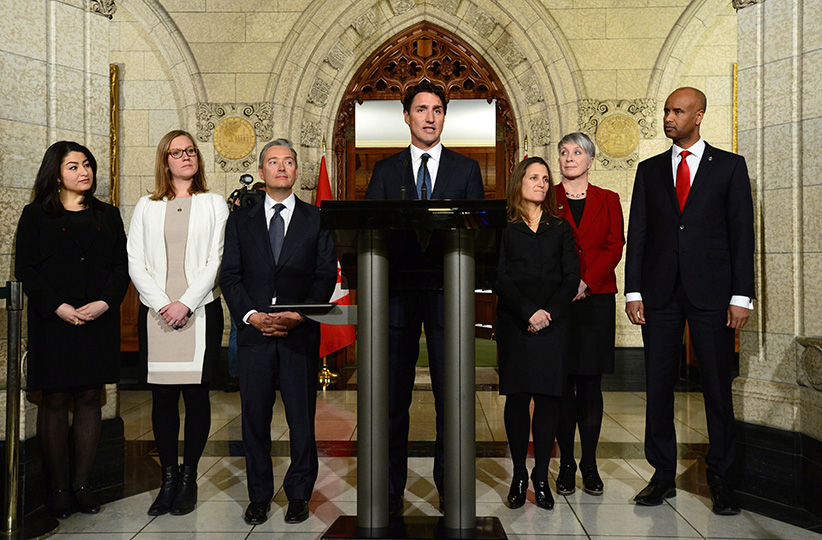

In Ottawa, PMO staffers had been up through unforgiving hours consulting with their White House counterparts, trying to sort out who was affected by the ban. At 4 pm in the National Press Theatre across from Parliament Hill, Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Ahmed Hussen would answer the questions roiling around the hastily concocted U.S. policy. The rookie MP had vaulted off the backbenches just 19 days earlier when he was sworn into cabinet; the House of Commons hadn’t even resumed sitting after the holiday break, so this was effectively his public introduction on the job.

A senior government official who spoke on condition of anonymity recalls glancing across the office during preparations for the press conference. “There was Ahmed in the middle of it all and he was just completely calm,” the official says. “I remember thinking to myself what a baptism by fire that was for a new minister, and then looking at him and thinking, ‘You know, it’s probably a little more manageable than Mogadishu was in 1992.'”

When Hussen, who came to Canada as a teenage refugee from Somalia, took his place before the cameras and reporters, he looked utterly calm and composed. He clarified the policy questions, then hewed carefully to the indictment-free line his government would tread over the coming weeks: other countries have the right to set their own policies, we can only speak to how we do things here.

When asked how he personally responded to the ban, given Somalia was on the U.S. list of verboten nations, Hussen gently batted away the premise of the question. “Yes, I was born in Somalia, but I took my oath of citizenship to this country 15 years ago. I am a Canadian,” he said. “I have spent most of my life here and I continue to be proud of our country, our ability to be generous, to continue to view those who seek protection as being welcome to this country.”

It’s virtually impossible to imagine a way in which the 40-year-old could be better suited to the cabinet job he now holds. He came to Canada fleeing the Somali civil war, and subsequently lived in Regent Park, a once-troubled and isolated downtown Toronto public housing project he would help rejuvenate and repatriate to the residents when redevelopment came calling. Later, he opened a law practice focusing on immigration law and criminal cases, particularly for young offenders.

MORE: Terry Glavin on why it’s time for Justin Trudeau to do brave things

Hussen, of course, sees the symmetry between his biography and the hefty file he now controls, but he’s distinctly understated about it. “Every public servant, every elected official, every minister of various orders of government, I think we are all informed by our lived experiences, and mine isn’t any different in that sense,” he says. “What is unique is that I happen to now lead the very department that I was once a client of. But I always tell people this: it really doesn’t say that much about me, it says much more about Canada, that this is possible in this country.”

Which leads to another way in which Hussen is uniquely suited to this post, at the precise moment when the debate about borders is so fiercely prominent in the world. His life story perfectly embodies the welcoming, globally-oriented Canada his government so wants to project. Hussen is the very best advertisement for this country’s immigration system—or, more precisely, for the best possible interpretation of how it can function.

Hussen arrived in Canada in 1993 at the age of 16, without his parents. He had two older brothers already in this country who helped with housing and the basics: buying winter clothing, registering for high school, accessing community services (his father died in 2000 and his mother lives in Nairobi). Hussen is quick to credit others who helped him, too, like his track coach, teachers and fellow students when he started high school in Hamilton. “They were very, very generous to me in my early years in Canada and I have never forgotten that,” he says. “I have always tried over the years to replicate that by helping those who came after me.”

After high school, Hussen moved in with one of his brothers in Regent Park. That’s where George Smitherman, a former Ontario MPP who represented the riding that included the neighbourhood, got to know him. A major redevelopment was in the works, so a group of residents started meeting, along with Smitherman, to ensure they had a voice in the process. By 2002, Hussen had co-founded the Regent Park Community Council. “We took a stand that said even though we welcome redevelopment, we also wanted to make sure that in that process, the people of Regent Park were revitalized, that the community was revitalized,” Hussen says.

Smitherman came to think of Hussen as “a gentle giant”: tall but slight, he possessed a presence and maturity that didn’t match his years; people simply listened when he spoke. “He could gently peddle a strong argument,” says Smitherman. “He seemed to me to have a well-developed—maybe instinctive—sense of how to carry himself.”

Hussen focused on concrete, pragmatic changes: isolated pockets of Regent Park were linked with green pathways, and University of Toronto professors were brought in to offer free classes. Basic public services like mailboxes were installed. In the many interviews Hussen gave in the thick of redevelopment planning, he would mention visiting Wasaga Beach, a town two hours north of Toronto that had roughly the same population as Regent Park. There wasn’t a single mailbox in his neighbourhood, but there were 22 in Wasaga Beach, he noted—he knew, because he’d counted them.

Hussen moved out of Regent Park around 2005, but he still visits that “mini-city” when he can, and he’s always amazed by the changes. “I had a lawyer friend, for example, a number of months ago who told me, ‘Hey, I’m moving into Regent Park,’ ” he says. “That’s something you would never have heard many years ago.”

Hussen volunteered on one of Smitherman’s campaigns, and he was spoken of so highly that he was hired as an assistant in Dalton McGuinty’s office when the Liberal leader was in opposition at Queen’s Park. After McGuinty’s party formed the government in 2003, the premier also became minister of intergovernmental affairs, and Hussen was hired as the legislative assistant and issues manager in that office.

Gerald Butts, now principal secretary to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, was McGuinty’s principal secretary at the time. One evening he had a friend visiting and he forgot something at the office, so they stopped by on their way out for dinner. Hussen had taken his oath of citizenship that day, and Butts introduced his colleague and told his friend he’d just become a Canadian citizen. As it happened, the friend visiting was Trudeau. Hussen recently reminded Butts of the conversation and recalled what his future boss said in response: “Welcome to the best club in the world.”

Arnold Chan, now the Liberal MP for Scarborough-Agincourt, was the senior advisor in McGuinty’s ministry office when Hussen worked there. He would get a call from the premier requesting, say, a briefing on Burma. Chan and the civil servants around him would be clueless, but eventually they learned to just send Hussen to brief the boss. “He’s very broadly read, very detail-oriented, and the most esoteric topics were already in that noggin of his,” says Chan. “He’s very soft-spoken, but my God, is he super-smart.”

Hussen left McGuinty’s office to attend law school at the University of Ottawa, after completing a history degree at York University. He saw a law degree as the way to further push the issues he cared about. He practiced for about five years, focusing on criminal defence, mainly for young people, and immigration and refugee cases.

Around the same time, Hussen became a prominent voice of the Somali diaspora, as national president of the Canadian Somali Congress. In 2011, he testified before the Homeland Security Committee in the U.S. about Al-Shabaab recruitment and radicalization efforts in the Canadian Somali community. Hussen traced the statistics of vastly lower median incomes, higher unemployment and school drop-out rates that revealed a young immigrant community still finding its feet. “After fleeing a civil war that gripped Somalia in the late 1990s, the Canadian Somali community is now undergoing the growing pains of integration into the larger Canadian mainstream society,” Hussen said.

He also spoke as “a Canadian Muslim who is proud of my faith and heritage” about how Canadian and American values of democracy, liberty, rule of law and human rights fit with his faith, and how Muslims can in fact best practice in countries that enshrine those. “The civil rights of our community members must obviously be protected, but it is equally important to disseminate these integration-friendly messages in order to contribute to a process where our community emphasizes the defence and attachment to the countries of Canada and the United States,” he said.

A few years later, when Hussen garnered 46 per cent of the vote and defeated NDP incumbent Mike Sullivan to take York South-Weston, a working-class and immigrant-heavy riding in Toronto’s west end, in the 2015 federal election, he became the first Somali-Canadian elected to Parliament. “Sure, I’m proud to be the first Somali-Canadian to get into elected office, but my history has indicated my ability to work with everybody and I intend to do that,” he told CBC the night of the election.

As an MP, he introduced a private member’s bill in May 2016 that would allow the federal government to require assessments of the “community benefits”—social or economic boosts such as job creation or the improvement of public space—derived from infrastructure projects. In the House, he has spoken about the budget, his concern over the proposed closure of a refugee camp in Kenya and against a Conservative MP’s call for the Canadian government to declare the treatment of Yazidis and others by ISIS a genocide. “The sentiment of the opposition’s motion is commendable, but sentiment is not enough,” Hussen argued. “Political declarations do not result in justice for victims of atrocities. What is needed is an impartial, independent determination by a competent court.”

Still, Hussen was not exactly a high-profile MP, and when he was tapped to take over the immigration file from veteran John McCallum—who subsequently resigned his seat and was named ambassador to China—the reaction was largely, “Who?” Hussen says he had no sense this was coming, but he was “very, very honoured and really touched” that the Prime Minister handed him this file. “I’ll be frank: it’s a big job, and he didn’t start as a parliamentary secretary, so he didn’t have the opportunity to get seasoned on the brief,” says Chan, who remained friends with Hussen after both left McGuinty’s office. “But I’ve never doubted his intelligence. So for me, his only major challenge is the cut-and-thrust, and the speed with which things will transpire in his life.”

Chan exudes a warm, fatherly sort of pride toward his colleague, despite being only nine years older. Hussen has three sons aged seven, three and five months; Chan’s three sons are just about a decade older, and he’s warned Hussen of how hectic it will be juggling everything now. Chan echoes others who know Hussen, in remarking on how he manages to be quietly commanding. “I think the challenge sometimes is in the heat of the bright lights, some people might take that (soft-spokenness) as a form of weakness. I would never take that as a view, that he won’t see through the issues or that he’s going to act in a capricious way, or that there’s a soft underbelly to him,” Chan says.”There isn’t.”

In fact, the PMO saw Hussen’s “preternatural calm” as a major asset in this portfolio, the senior government official says. The Liberal government—not unlike vast swaths of the U.S. government apparatus, apparently—didn’t know exactly what the Trump administration had planned, but it was clear from the campaign that immigration would be a hot file. Hussen was also seen as an ideal fit because he had, quite literally, been there. “We wanted to make sure there was someone in the control room who really understood what it was like to be on the shop floor,” the official says.

Hussen is almost comically understated about his dramatic public introduction to the job, conceding only that it was a “very interesting” weekend. “I’ve always learned most when I’m placed quickly in a situation where I have to deal with something,” he says. “It was a very steep learning curve to get right into it, but I have a very good staff and supportive department officials.”

When asked about his seeming reluctance to respond to issues like the U.S. travel ban from a personal perspective, Hussen returns to a familiar line in spelling out the various pieces of his identity and history. “I’m very happy and proud of my Somali heritage, but I also make it a point to emphasize that I’m a Canadian citizen, and I’m a Canadian,” he says. “This is where I have spent more of my life, this is home for me and this is the society I have grown to cherish.”

For Hussen, it’s about being proud of his roots, but recognizing that he is a citizen of one country now: Canada.