I have questions about le unvax tax

Paul Wells: There’s at least a decent case to be made for François Legault’s plan to tax unvaccinated Quebecers. But don’t be surprised if he drops the idea.

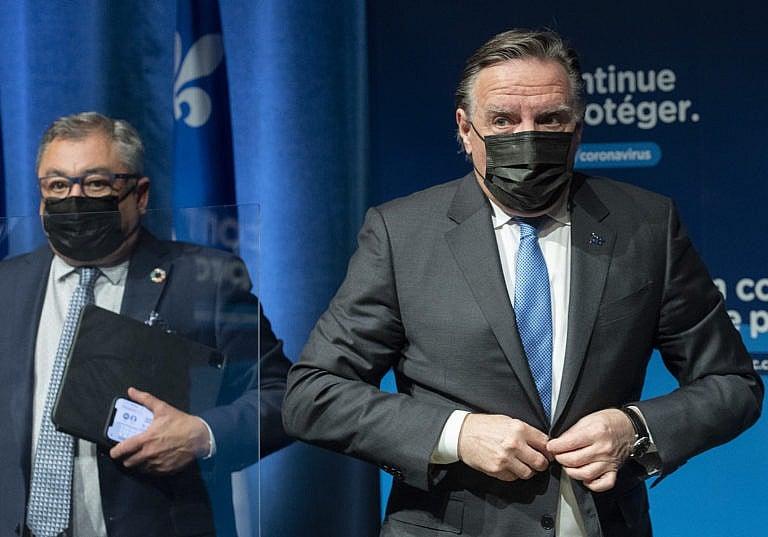

Legault leaves a news conference in Montreal, on Dec. 30, 2021 (Graham Hughes/CP)

Share

I admit I was kind of intrigued when François Legault, the Quebec premier who’s never short of new ideas, announced he’s thinking about levying a “health contribution”—essentially, a hefty tax—against Quebecers who aren’t vaccinated. As you’ll have heard, thinking about it is so far all Legault is doing. At the Tuesday news conference where he announced it, the premier was unable to answer basic questions: how much do you have in mind? (More than $100, he said, but… that’s all he said.) When does it start? How do you collect the levy? (Through the tax system, he said, which raises a lot of second-order questions.) Would people pay once, or for as long as they stay stubborn? And the big one: is this constitutional? “We’re working on the legal part,” Legault said cheerfully. Welcome to the new Quebec-made electric vehicle for everyone. We’re working on the engine and the battery.

But I felt like making at least a minimal case for Legault’s unvax tax. Start here: it’s a new idea. Federalism used to be a system for testing new ideas in multiple jurisdictions so the best ideas could be shared and the bad ones weeded out. And Legault’s tax, or fee, or contribution, seeks to do, directly, what a lot of governments are doing with exquisite timidity: make it clear that there are social and economic costs to this endless lockdown, and the people who are playing by the rules—masked, vaxxed, boosted, isolated, bubbled—are getting a bit tired of hearing the unvaxxed mask-around-my-chin set call themselves martyrs to freedom. Especially when the main justification for an umpteenth round of new social restrictions is an intensive-care capacity that is strained, disproportionately, by people who are proud of turning down vaccines but a bit more relaxed about accepting life-saving treatment.

READ: It’s time to switch to an N95 mask in the battle against Omicron

What’s to be done about this? Well, on the centre-right, some people are blue-skying about a public-private mix in health care provision, which I’m afraid would represent a highly unlikely cultural revolution and which, even if it happened, would sure take time to implement. Others, like Emmanuel Macron, want an essentially never-ending, but decorously piecemeal, harrassment program against the unvaccinated. Macron used a colourful term, “emmerder,” but his plan is actually timid: if the unvaccinated are the main problem, why not face it, and them, head-on?

Early objections to Legault’s scheme are not entirely persuasive. André Picard says a tax would be punitive. Well… sure? It would be designed to be punitive. André lists several current or potential measures that limit what the unvaccinated may do, contrasting it with this levy that they would have to pay. Among the people who probably won’t find this a persuasive difference are the unvaccinated, who already feel plenty puned. Then he says “denying health care to the unvaccinated” would be “wrong-headed.” Maybe. Except it’s already happening in isolated cases in a lot of places due to defensible triage considerations.

And more to the point at hand, Legault’s fee wouldn’t deny anyone health care. It’s like a tip jar for swearing: if you do the societally disapproved thing, or decline to do the societally approved thing, you have to put a quarter in the tip jar. But if your lungs give out, you still go sailing through the front door at the local hospital. (Assuming there is one.) In fact, whenever Quebec government lawyers get around to working on the legal part, this disconnect between the fee and the health-care system might be what saves the whole scheme: at no point during any Quebecer’s interaction with the health-care system would any levy be demanded as a condition of receiving care.

So: Legault’s scheme has the virtue of broad conceptual clarity—some folks are holding everyone else back, so they should pay for the privilege—even if it’s a thicket of confusion on the details. It might even be legal. And as a notion, I fail to find it particularly horrifying. “There’s this guy running a government who wants to tax behaviour” is not exactly a man-bites-dog novelty.

But I still think Legault’s unvax tax is poorly conceived. And I won’t be at all surprised if he abandons it before implementing it.

When you think about it, it’s easy to imagine why Legault would be interested in penalizing the small number of Quebecers who refuse to be vaccinated. He’s had a pretty good few years penalizing small numbers of Quebecers. That’s at least the effect of his proposed reinforcement of Quebec’s language laws, and it’s pretty clearly the point of his law denying some public-service jobs to people who don’t dress the way Legault would have. A lot of people don’t like either law, 21 or 96, but they’re way outnumbered in Quebec, and Legault almost always prefers to side with most Quebecers against some Quebecers. There’s at least a soft populism there that can be unnerving but that also helps explain his political success.

Indeed, few things are likelier to get under Legault’s skin than the suggestion that he doesn’t know where M and Mme Average Quebecer live. There was a weird moment last year when he seemed not to know what the average rent was. He came in for some ribbing from the opposition parties. Hey, bigwig airline executive turned premier, bet you don’t know how much milk costs either. It freaked him out. “I’m proud to say I come from the very middle class,” he objected. “I still have many friends who come from the very middle class. I take care to stay close to the people and I’m very connected to reality.”

So, during a winter when he’s coming under increasing criticism for imposing unpopular and dubiously effective restrictions on everyone—Quebec’s notorious COVID curfew first among them—it’s not entirely out of character for Legault to look around for a pariah group he can dump on instead.

READ: The roadblock to full pandemic recovery: ‘Pockets’ of unvaccinated Canadians

I just think this time he might have chosen poorly.

The classic Legault out-group is one whose characteristics are pretty set—people who weren’t raised in French, or people whose conception of their faith includes strong ideas about wardrobe. Borders around those groups aren’t porous. You can’t accidentally become an anglophone or an observant Muslim, and you don’t exit those groups without effort. So it’s easy, I think too easy, to set up a politically advantageous us-and-them dynamic.

But “the unvaccinated” designates a group that shrinks every day. Even now, after a year of vaccine drives, it’s not coterminous with obstinate conspiracy-theory-driven refusal to be vaccinated. Which helps explain why even the thrice-vaxxed, well-masked, tight-bubble civic leaders in COVID virtue often have a hard time working up real anger against those who aren’t yet playing along. Ideally, after all, we all hope we’re only months away from a world in which these distinctions will no longer be salient, because the coronavirus will—knock on wood, again—be fading from its unwelcome role as the main global influence on social organization.

Despite the recent and understandable frustrations of the fully-vaxxed, I don’t think vaccination status offers a steady, durable context for us-against-them politics of the kind that Legault plays well. Add in all the logistical challenges of applying his policy, and I won’t be at all surprised if he simply drops the idea. Here again there would be precedent.