Inside the ‘progressive’ think tank that really runs Canada

How a small think tank called Canada 2020 gave rise to Justin Trudeau and became the country’s new nexus of power

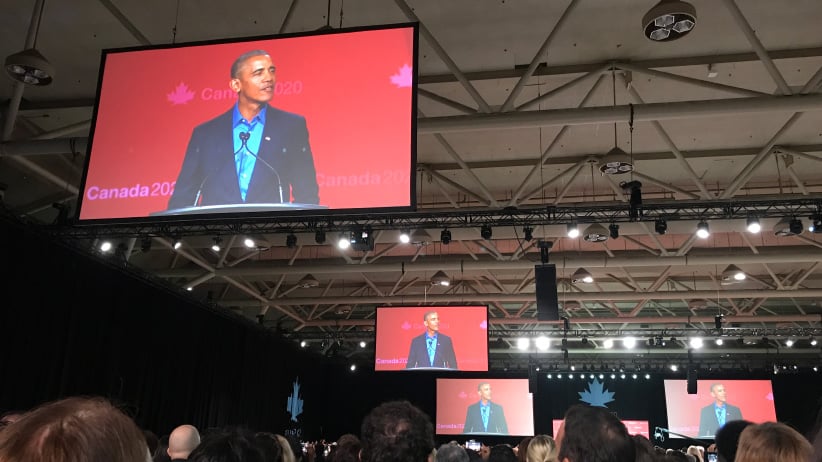

President Barack Obama at the Canada2020 event. (Lisa Zarzeczny)

Share

In late September, Barack Obama spoke in Toronto at a brilliantly produced event offering the perfect forum for his uplifting “Yes, we still can” message. The occasion also provided a triumphant, brand-burnishing moment for its organizer, Canada 2020, the Ottawa-based enterprise that bills itself as “Canada’s leading, independent, progressive think tank.”

Canada 2020’s scarlet-and-white logo was plastered throughout the Metro Toronto Convention Centre—over the stage, on the T-shirts worn by helpful young volunteers. Screens overhead displayed logos of the event’s many sponsors (among them Shell, Bell, Facebook and Canada Goose) as well as images from past power schmoozes for which Canada 2020 is known—conferences, panels and summits attended by “thought leaders,” politicians, bureaucrats, entrepreneurs, journalists and academics who discuss Big Ideas—from inclusive prosperity to digital democracy. Images of Hillary Clinton, Richard Branson and Larry Summers, former U.S. treasury secretary, flashed by on the screen, as did a parade of big-L Liberals, prominently Justin Trudeau, members of his cabinet, and Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne. Two of those ministers, Bill Morneau and Navdeep Bains*, sat in the audience, as did Wynne.

When Canada 2020 co-founder Susan Smith took the stage to introduce Canada Goose CEO Dani Reiss, who had the plum gig of introducing Obama, Smith called the not-for-profit a place where “public policy and cool collide.” She referred to ties between Canada 2020, the Liberal Party and the Obama Democrats. Trudeau’s first official trip to Washington in 2016 saw the “handing of the progressive torch from Barack Obama to Justin Trudeau,” Smith said, noting Canada 2020 was there: back then, they had “thought it would be cool to launch a policy lunch with the Prime Minister” and threw a “kick-ass” party. The Obama event in Toronto was the largest Canada 2020 had thrown, Smith told the crowd of some 3,000.

As such, it represented a milestone for the organization, founded in 2006 amid the ashes of federal Liberal defeat. Post-2015 Liberal sweep, Canada 2020’s symbiotic relationship with the Liberal Party and the Trudeau government has put it under the microscope, with closer scrutiny being paid to connections ranging from the party renting space from Canada 2020 during the last election to its president, Tom Pitfield, vacationing in 2016 with Trudeau on an island owned by the Aga Khan—a trip now being investigated by the ethics commissioner.

Tom Mulcair, then NDP leader, likely thought he was delivering a blow late last year when he called out Canada 2020 as “simply a wing of the Liberal Party of Canada.” But the descriptor doesn’t begin to capture the power nexus the organization has come to represent—it’s less the Liberal Party’s wing and more its spine. The enterprise has been instrumental in shaping the current governing party, from its policies to its leader. It’s an incubator of—and showcase for—bright, rising Liberal talent. A year and a half before running for Bob Rae’s vacated seat, Chrystia Freeland appeared on a January 2012 Canada 2020 panel, “The Canada We Want in 2020: Income Disparity and Polarization.” In the wake of the federal “cash for access” scandal, Canada 2020 has been accused of acting as a gatekeeper to power via its events, which see industry leaders and lobbyists rub elbows with cabinet ministers and senior government officials.

To study Canada 2020, it’s useful to have some grid paper to better map its myriad interconnections, many which reveal the two degrees of separation that define Canadian politics. Three of its co-founders—Smith, Tim Barber and Eugene Lang, all well-connected Liberals—were also principals in the Ottawa-based Bluesky Strategy Group, a firm whose services include lobbying and media relations (Lang left Bluesky and Canada 2020 in 2013). Pitfield, the fourth named co-founder, has impeccable Liberal bona fides: the son of Senator Michael Pitfield, clerk of the Privy Council when Pierre Trudeau was PM; a lifelong friend of Justin Trudeau, helping him write the stirring 2000 eulogy to his father that paved his way to political office. Pitfield, who also worked for the Canada China Business Council founded by billionaire Paul Desmarais, is married to Anna Gainey, elected president of the Liberal Party of Canada in 2014; he ran digital strategy for Trudeau’s leadership bid and also for the 2015 federal Liberal campaign.

Connections between Canada 2020, the Liberal Party and Bluesky can look like a Venn diagram on steroids. Bluesky and Canada 2020 are based at 35 O’Connor St., where the party rented space for a temporary “volunteer hub” during the election. Pitfield intersects with the Liberals professionally via his company Data Sciences Inc., which has an exclusive agreement to manage the party’s digital engagement; two Data Sciences staffers sit on the Liberal Party’s board of directors.

FROM 2015: Inside the making of a Prime Minister: Trudeau’s epic journey

Where there is Liberal news, there’s often a Canada 2020 connection. Take the recent controversy over Rana Sarkar, named Canada’s consul general to San Francisco at a salary twice the listed compensation. Media focused on his friendship with Gerald Butts, Trudeau’s senior adviser. But Sarkar has deep Canada 2020 links, too: he was named to its advisory board in 2015, is the author of a chapter in one of its “policy road maps,” and has participated in its speaker series. The bottom line: to understand this big-L Liberal moment in Canadian politics, you have to understand Canada 2020.

When asked about the organization’s genesis, co-founder Tim Barber points to an Oct. 2003 New York Times Magazine story, “Notion Building,” about the Center for American Progress (CAP), which had recently been founded by John Podesta. Bill Clinton’s former White House chief of staff (and later an Obama adviser) wanted to take on the right with an enterprise that could book liberal thinkers on cable TV, create an “edgy’’ website, and recruit scholars to research and promote new progressive policy ideas. CAP wasn’t an organ of the Democratic Party, Podesta insisted, though history points to it being just that.

Podesta hates the term “think tank,” Barber says. “I do too. It’s way too passive and conjures days gone by. His view was that there’s an opportunity for organizations to put as much time into marketing and communicating big ideas as coming up with those big ideas.”

Canada 2020’s first conference, “Progressive Policies, Practical Solutions,” set the stage in June 2006, attracting some 150 people from government, business and academia to Mont Tremblant, Que. Most were Liberals, eager to refocus a party riven by infighting and lack of focus. Former U.S. vice-president Al Gore gave the keynote. Barber wryly dismisses media reports that Gore charged US$80,000: “It was more like $100,000.” (When asked what Obama charged, Barber won’t say, offering only: “It was competitive.”)

The party’s old guard (Bill Graham) mingled with new (Butts). John Manley, Jean Chrétien’s right hand, and Anne McLellan, right hand to Paul Martin, co-chaired. Revitalizing the party was certainly the objective of some, McLellan tells Maclean’s: “It was picking ourselves up off of the mat and saying ‘Let’s do better next time.’ ”

Justin Trudeau also was on the scene, in sandals and T-shirt. The 34-year-old, then working on a master’s in environmental geography, was on Canada 2020’s first advisory board, as was Butts. Pierre Trudeau’s eldest son was then emerging as the party’s new, yet familiar face. He’d co-hosted a tribute to Jean Chrétien at the 2003 leadership convention and was named chair of Liberal “Youth Renewal” in 2006. The Liberals are “doing a lot of soul-searching right now,’’ Trudeau told the Globe and Mail, calling the event ‘‘a chance to actually start thinking long-term again.” Eight months later, he announced his run for the Liberal nomination in Montreal’s Papineau riding. Five years after winning the seat, he was Liberal leader.

Trudeau’s rise would be abetted by the machinery that helped Obama win the presidency in 2008, forged via connections between Canada 2020, the Liberals and Global Progress Initiative, an international network also founded by Podesta; Canada 2020 became its Canadian hub. Matt Browne, a senior fellow at CAP, sits on 2020’s impressively diverse advisory board. In 2011, the Liberals licensed the Democrats’ VoteBuilder database, modified it and repackaged it as “Liberalist.” Trudeau’s team, including Butts and Katie Telford (now the PM’s chief of staff), attended a 2012 CAP event on lessons from the Obama campaign. Precision Strategies, run by former Obama strategists, had provided “Team Trudeau” with advice since 2013, Politico reported in 2016. CAP’s Global Progress Initiative held international events attended by the “Trudeau Liberals and the guys from Canada 2020,” Browne told the Globe and Mail in 2016. Policies from CAP’s Inclusive Prosperity Commission—pledging to address income inequality and dispensing with a zero-deficit target—found their way into the Liberal platform.

READ: Why some businesses might be OK with a populist Trudeau budget

Once party leader, Trudeau was given a big-thinker platform at Canada 2020 events. In 2014, he delivered the keynote at its first annual conference, where he infamously remarked during a Q & A that Canada should consider a humanitarian mission in Iraq rather than “trying to whip out our CF-18s and show them how big they are.”

Pitfield incorporated Data Sciences in 2014; he was named Canada 2020’s president in 2015. As one Ottawa insider puts it: “Tom was put in the window to demonstrate affinity with a party that would play with them.” The Liberals’ sweep to power, and the excitement accompanying it, heightened Canada 2020’s profile; Trudeau and his ministers were draws at Canada 2020 events. (Not everyone was thrilled; one observer notes the oxygen Canada 2020 took up diverted attention from long-standing “progressive” think tanks like the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and the Broadbent Institute). The PM appeared at a 2020 after-party following the June 2016 North American Leaders’ Summit with Obama and Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto; it saw ministers mingling over drinks with those who lobby them. Trudeau is also front and centre at the annual Global Progress Summit in Montreal, a gathering of global movers and shakers co-hosted by Canada 2020 and CAP; in 2016, he conducted an “armchair discussion” with London Mayor Sadiq Khan.

Trudeau’s cabinet also headlines frequently. In 2015, Catherine McKenna, newly named minister of environment and climate change, gave the keynote at Canada 2020’s annual conference. In June 2017, Harjit Sajjan, Bill Morneau, Kathleen Wynne and Ontario MP Liz Sandals all appeared. At the time, Bluesky was lobbying Sajjan’s department on a replacement for CF-18s and the PMO on behalf of the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, a Canada 2020 sponsor.

Canada 2020’s sponsorship list grew with time, but it was tough going in the early days, McLellan says. “We didn’t know we would make it.” CAP began with a multi-million-dollar budget, thanks in part to donations from financier George Soros, and now has a staff of hundreds. No Soros-like figure bankrolled Canada 2020, which has a full-time staff of three, says Barber. There was a “Founders Circle” but he doesn’t talk about it: “That ship has sailed. Now we have ‘sustaining partners’—basically people that like what we do.” That list includes more than 30 of the country’s biggest corporations, among them TD Bank, Amgen, Manulife, Suncor, Enbridge, Via Rail, RioTinto, Telus and Rogers (the parent company of Maclean’s).

Barber waves off a minor furor in the House over the federal government paying $15,000 to Canada 2020 for an innovation conference at which Infrastructure Minister Amarjeet Sohi spoke. “Oh my god!” Barber says mockingly. “Yeah, but it cost $600,000 to put on.” During the Harper years, they’d also received small funding amounts, he says.

As a not-for-profit, Canada 2020 isn’t required to make financial statements public. Nor will it say how much sponsors donate, only that sponsorship is renewed annually and that everyone receives equal ranking, no matter what they donate. Sponsorship is vital, says Barber; they try to make as many events as possible free.

To retain not-for-profit status with the Canada Revenue Agency, a group must be non-partisan, says Donald Abelson, a political science professor at Western University and author of Northern Lights: Exploring Canada’s Think Tank Landscape. “Non-partisan doesn’t mean being non-ideological,” he adds. “It means a think tank can’t oppose a candidate or endorse a candidate or give money. They can say, ‘We’ve written a paper on UI and endorse the direction of the government.’ ”

Barber rejects any suggestion Canada 2020 is a big-L think tank, noting that conservatives like Brian Mulroney and former cabinet ministers Jason Kenney and John Baird have also appeared at events. “I prefer ‘progressive,’ ” he says.

Still, there’s no question Canada 2020’s priorities dovetail with the federal agenda. This year, economist Mike Moffatt, an assistant professor at the Ivey Business School (and a former Maclean’s contributor), was named the federal government’s “chief innovation fellow.” He’d been a senior associate at Canada 2020, who received funding for a volume on innovation published this year.

Canada 2020 events have also fed Liberal Party fundraising, a fact laid bare in a 2016 WikiLeaks hack of the email account of John Podesta, then Hillary Clinton’s campaign chairman (the ironies here abound). An email from Clinton aide Huma Abedin stated “Trudeau’s team” had been told Clinton was displeased that her 2014 speech at a Canada 2020 event was used to fundraise (Liberal.ca invited donors to join a draw to win a return trip to Ottawa, breakfast with the PM and to hear Clinton speak). “This was supposed to be a completely apolitical event,” Abedin wrote. A similar contest was held before Trudeau’s trip to Washington. The prize: a trip for two to D.C. and participation in “exclusive events” with Trudeau organized by Canada 2020 and CAP.

Concern about Canada 2020’s influence and tight ties with the federal government has already become an academic sub-genre. In his new book, Doctors in Denial: Why Big Pharma and the Canadian Medical Profession Are Too Close for Comfort, Joel Lexchin cites a two-day “health summit” sponsored by Canada 2020 and the Canadian Medical Association in September 2016 as running contrary to public health interests. The event, “A New Health Accord for All Canadians,” attracted a who’s-who of the health insurance and pharmaceutical sectors, including representatives of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, the largest U.S. pharmaceutical lobby group. Jane Philpott, then the health minister, attended with senior Health Canada officials, with Philpott speaking of the importance of improving Canadian accessibility to pharmaceuticals. Alliances between government, industry and the medical profession run contrary to public health interests, Lexchin, a professor emeritus at York University, tells Maclean’s. “Drug companies have a long history of actions damaging public health,” he says, “either in the prices they set or the facts the drugs they are interested in are the ones that generate the largest revenue, not those that meet highest public health need.”

READ: Q&A: Jane Philpott and Carolyn Bennett on their biggest challenges

In December 2016, Canada 2020 staged its “Second Annual Health Innovation Conference,” also attended by Philpott and senior departmental officials. The conference was chaired by two Canada 2020 advisers who lobby for the pharmaceutical industry: Shannon MacDonald, who works for Johnson & Johnson, and Kim Furlong, of Amgen.

Duff Conacher, co-founder of Democracy Watch, finds the in-plain-sight commingling of industry, government and lobbyists at Canada 2020 events confounding: “It blows my mind, it’s so blatant,” he says. “Canada 2020 has set up a structure that is non-criminal in terms of influence being peddled, but that is unethical and a violation of the Conflict of Interest Act.”

Neither Canada 2020 nor Bluesky are lobbying the government directly, the professor of politics and law at the University of Ottawa says. “But all big lobbyists who can afford it know that, if you want to influence Trudeau, you become a Canada 2020 sponsor; that will help you with your lobbying of the federal government. I don’t know how they believe there is this grey area.”

In November 2016, after the “cash for access” controversy that saw the government introduce new transparency rules, Canada 2020 rewrote its donor agreement, found on its website, to state donations are not “a means to gain access to, or obtain an audience with, any speaker, attendee or any other person at or connected with any program or event hosted or arranged by or on behalf of Canada 2020.” Conacher is skeptical: “They can say that. But you can’t claim that when factually it’s not true. If you do sponsor an event, you will get access to senior decision-makers in the government.”

The mandate letters Trudeau wrote to cabinet ministers and made public were useful to lobbyists, Joe Jordan, a former Liberal MP and now a Bluesky senior associate, told the Hill Times earlier this year: they “made it easier than in the past for lobbyists to see what the government wants to achieve and find common threads.”

Access is influence, says Conacher, who points to rule seven of the Conflict of Interest Act, which states no public office holder can give “preferential treatment to any person or organization.” And the government helped Canada 2020 hold numerous events, including one during Trudeau’s Washington visit, Conacher says. “I don’t think the Trudeau PMO and cabinet could prove that they have not given preferential treatment to Canada 2020.”

When these concerns were put to the PMO, press secretary Eleanore Catenaro noted that the “Prime Minister regularly meets with different organizations both in Canada and around the world, and is accessible to Canadians across the country,” in an email that provided a checklist of other organizations and events Trudeau has engaged with, including WE Day, the Atlantic Council, HeForShe and Fortune’s Most Powerful Women Summit.

Conacher is calling for the ethics commissioner to investigate how one organization is suddenly able to hold events ministers attend. “Each of those ministers would have to show that other organizations have invited us and we have shown up at the same rate.”

He’s not optimistic. Ethics commissioner Mary Dawson, on her third six-month, interim contract, appears beholden to the government, he says. In July, Democracy Watch filed a Federal Court case challenging the renewed appointments of the ethics commissioner and the lobbying commissioner. “We believe [Dawson] is in conflict of interest—she’s serving at the pleasure of the PM and will not be reappointed unless she pleases Trudeau.”

Conacher views Canada 2020 as the latest iteration of a federal tradition, likening it to the Frontier Centre for Public Policy during the Harper years and the Canada Policy Research Networks for the Chrétien and Martin Liberals: “the favoured think tank” that helps produce reports and hold events “that the government wants produced and held.”

Abelson, who studies think tanks, believes Canada 2020’s strength is self-promotion. “Has 2020 made its presence felt? Yes—in terms of media, events, workshops; it’s cited in Parliament,” he says. But its influence on policy is more difficult to determine at this stage. “They’ve focused on marketing and promotion. That’s only sustainable if you produce interesting, important studies that engage a number of stakeholder groups. You can’t rely on conferences and ties to high-profile people.”

For now, though, Canada 2020 is directing the conversation through its peerless command of imagery and visual cues—a mastery it shares with the Liberal Party. At the recent Obama event, Bruce Heyman, a former U.S. ambassador to Canada appointed by Obama, conducted a Q & A in which the former president praised “Justin” as a young leader representing “traditional values of democracy.” Heyman name-checked Canada 2020, once asking the former president: “What can Canada 2020 and the people in the room do for you?” referring to the Obama Foundation. Obama said he’d just asked 2020 organizers the same thing: “I asked them, ‘How can I help you? How can I help networks around the world?’ ”

Heyman’s presence offered yet another 2020 synchronicity: as a major Obama donor, he supported a president whose lessons informed Team Trudeau. Now he’s a Canada 2020 “special adviser,” working on a voluntary basis to, as 2020’s website puts it, “help think through our organization’s vision, mission, and yes, even branding (2020 is fast approaching, after all).” And lest we forget, so too is the next federal election.

CORRECTION, Oct. 12, 2017: An earlier version of this piece misidentified Innovation, Science and Economic Development Minister Navdeep Bains. Maclean’s regrets the error.