Jagmeet Singh’s Quebec problem

In a province where suspicion of religion in politics is a progressive impulse, the NDP leadership hopeful is facing an uphill battle

Ontario deputy NDP leader Jagmeet Singh launches his bid for the federal NDP leadership in Brampton, Ont., on Monday, May 15, 2017. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Nathan Denette

Share

The second most-popular story on Le Devoir‘s website as I write this is about mounting anxiety in the Quebec wing of the NDP over Jagmeet Singh’s candidacy for the party’s leadership. “Several activists are panicking” at the thought, the story says.

The problem? Singh, a practicing Sikh, wears a turban and kirpan. “To have a leader who’d wear ostentatious signs” of his religious affiliation, “we are not ready,” Pierre Dionne Labelle, who was an NDP MP from 2011 to 2015, says on the record. “Would I be at ease with that? I don’t think so.”

This is the first time Le Devoir has found a New Democrat willing to speak on the record about concerns over Singh’s candidacy. Several others seem willing to share similar concerns off the record. The story also adds two cases where Singh’s positions in provincial politics could arguably have been influenced by his religious beliefs: a private member’s bill that sought to exempt Sikhs from having to wear motorcycle helmets, and a member’s statement over the provincial Liberal government’s controversial changes to the primary-school sex-education curriculum.

I could quibble with the latter of these examples. Singh’s statement on the sex-ed curriculum could have been made by Patrick Brown, the province’s Conservative leader, who is not Sikh. “The lack of inclusive consultation before announcing the curriculum was disrespectful to parents in my constituency,” part of Singh’s little speech, is a stock line in much of the opposition to the curriculum change.

But it’s less interesting to debate these points than to note that the anxiety Le Devoir chronicles exists, that it’s a challenge to the Singh candidacy, and to try to understand why these concerns are being expressed most loudly by the NDP’s Quebec wing.

Luckily we have a recent poll to guide us.

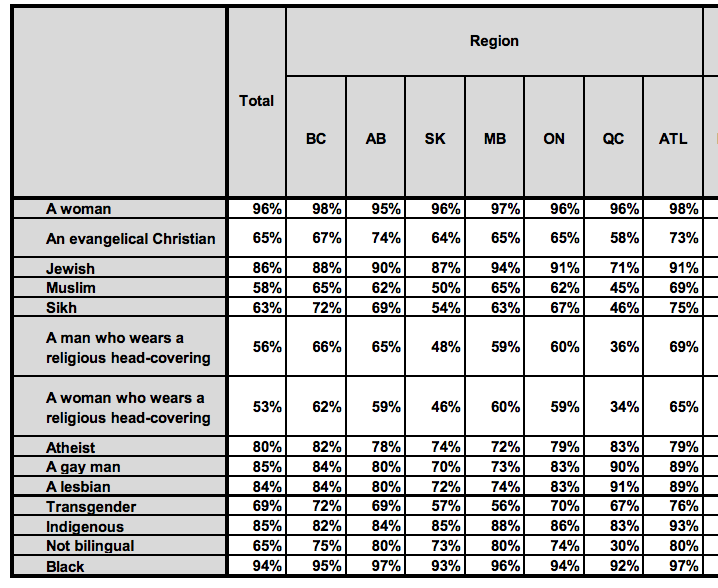

On June 26 the Angus Reid Institute published the results of surveys in the United States and Canada on attitudes towards diversity in political leadership. The Canadian results come from a randomized sample of 1,533 members of Angus Reid’s online panel; full methodology can be found here. Respondents were asked whether they would vote for a party led by a woman, a gay man, a man or woman wearing a religious head covering, and so on. This produced all sorts of fun cross-border comparisons—68 per cent of Canadians expect an atheist Prime Minister in the next 25 years, against only 37 per cent of Americans who expect an atheist President. But the internals from the poll suggest other useful comparisons. Here’s the Canadian regional table showing responses for various questions that begin, “Would you yourself consider voting for a party led by a person who is…”

Support for a Sikh-led party is only 46 per cent in Quebec, the lowest regional score in the country by eight points. On the generic “…man who wears a religious head-covering,” support is lowest in Quebec by 12 points. Support is also lowest in Quebec for parties led by Muslims, by Jews, and indeed by evangelical Christians.

This would probably be a good time for this Maclean’s writer to say the Angus Reid data don’t show a generalized inability among Quebec respondents to show “openness” to “difference.” No, the results are way more interesting than that. In fact, Quebec respondents were markedly more likely than respondents in the rest of Canada to support parties led by a gay man, a lesbian or an atheist. And there was no marked difference between Quebecers and other respondents when the hypothetical party leader was transgender, Indigenous, black or a woman.

In no other part of the country do the results line up as they do in Quebec: markedly less likely to support parties whose leaders wear some visible sign of their religious affiliation, markedly more likely to do so if their difference is expressed in some other way besides religion.

There’s an obvious explanation for this, but it rarely gets mentioned whenever the debate over so-called “reasonable accommodations” rears its head in Quebec or outside. It’s that Quebec has a markedly different cultural history with organized and visible religion than much of the rest of Canada.

Many older Quebecers, those whose memories stretch back before the mid-1960s at least, have personal memories of a time when the Roman Catholic church had a strong influence over public affairs. Even most younger Quebecers will have been taught, in great detail, about the period before the Quiet Revolution. And the Catholic church was pretty big on ostentatious displays of religious affiliation.

(You needn’t take my word on any of this. Marie McAndrew, a professor at the Université de Montréal’s faculty of education, has written often and thoughtfully on the “reasonable accommodations” debate and its cultural roots. In this representative piece, she writes: “…[W]e must remember that the people of Quebec who are of French-Canadian origin have a specific and usually more negative relationship with religion than people in the rest of Canada…. For most people born before the 1960s, in fact, the association between religion and public space evokes bad memories or at least memories that are incompatible with their democratic ideals.”)

The Quiet Revolution in Quebec was specifically a rebellion against religious influence. Progressive politics in many other parts of the country has been a politics of generalized tolerance; in Quebec progressive politics was often a politics of specific resistance. I lived in Quebec for five years and have written about its politics in instalments for nearly a quarter-century since, and I find this is one element of the debate over religion and politics that’s hardest for many non-Quebecers to grasp: suspicion of religion in politics is often a progressive impulse in Quebec politics. (Emphasis on “often,” as in, “of course not always, in Quebec or anywhere else.”)

That ex-NDP MP, Pierre Dionne Labelle, who’s quoted in the Le Devoir story? He was an anti-poverty activist before entering electoral politics. One of his few spotlight moments in the last Parliament was the day he stood in the Commons to complain that MPs had found themselves applauding a conservative American Catholic cardinal who’d visited the House the day before.

The Angus Reid results suggest that if one of the NDP leadership candidates were a lesbian atheist, she’d likely receive a better response in Quebec than in any other region (as long as she spoke good French, another deal-breaker according to Angus Reid). But if she wore a headscarf representing any religious affiliation (including, I suspect, that of a practicing Catholic; I do wish the survey had tested that hunch) she’d be out of the running.

This paradox hurts the NDP more than any party, because the NDP is uniquely whipsawed by its contradictions. Outside Quebec it is, or wants to believe it is, or can be at its best moments, the party of a generalized laissez-faire openness to religious, ethnic and sexual diversity. The kind of party that could proudly run Monia Mazigh as a candidate. Inside Quebec it’s a party that would regard a nice guy in a turban as a uniquely alarming prospect, with clear echoes of Quebec’s past. It’s not clear how to reconcile these two progressive traditions. It’s to Singh’s credit that he’s sought to confront the challenge head-on, with a genuinely charming video ad that shows him explaining his affinities for francophone Quebec while he dons his turban. Early evidence suggests the ad won’t be enough.