Jim Prentice, the politician who wasn’t there for politics

‘He knew what team he played for, but I always got the feeling he had the bigger picture in mind’

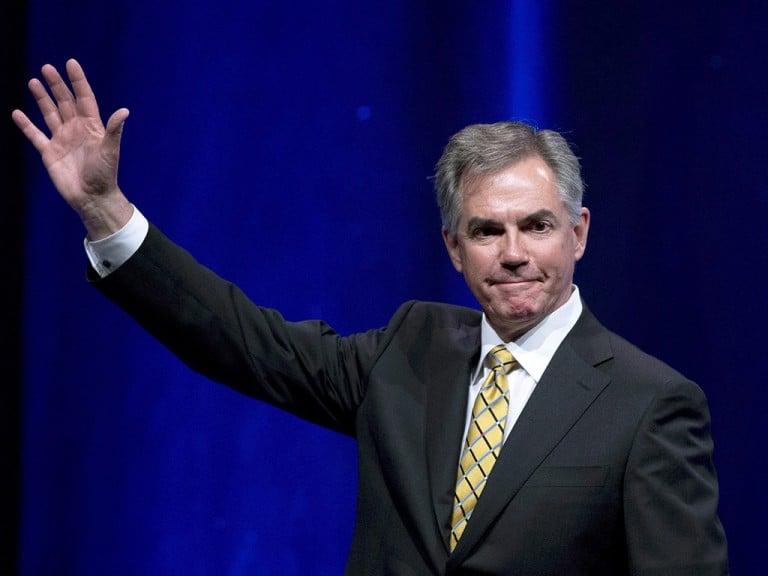

Outgoing Premier Jim Prentice waves after his speech at the Alberta PC Dinner in Calgary, Alberta on Thurs. May 14, 2015. (Larry MacDougal/CP)

Share

On the left side of Stephen Harper’s first government front benches in 2006 sat some master-class partisan hecklers: Peter MacKay, Stockwell Day and John Baird, along with a soon-to-be-prominent pair whose voices could carry well enough from far back, Pierre Poilievre and Jason Kenney. But the man who sat closest to the prime minister’s left ear wasn’t really there to lob insults and glib comebacks across the Commons floor. Jim Prentice would let his competitive streak show in bouts of MP hockey, or yuk it up over after-work beers. But when he was on Parliament Hill, and the Speaker, prime minister or a committee chair was presiding, Prentice was there to govern, not play games.

The majority of tributes to Prentice, once news of his death in a plane crash near Kelowna, B.C. on the night of Oct. 13 broke the following day, celebrated him as a professional devoted to public service. Few discussed the man’s politics, despite the fact that he spent much of his 60 years in it—from the 1976 federal Tory leadership campaign of Joe Clark to a crushing defeat last year after seven months as Alberta premier.

“There was a subtlety about Jim’s politics,” MacKay told Maclean’s. “He didn’t always wear it in an outward, partisan fashion, but it was there. He knew what team he played for, but I always got the feeling he had the bigger picture in mind.”

Some politicians seem enraptured by the performance of it all. Prentice might like us calling him a legislator, not a politician; for him, politics appeared to be mainly the conduit through which he got the chance to shape policy and the way Canadians and Albertans would be governed.

From the archives: Jim Prentice: The teammate

Yet his final act in public service turned out to be purely political, and one of the biggest collapses in the history of Canadian politics. As premier, Prentice helped consolidate his Alberta Progressive Conservatives into a 72-seat majority with the mass floor-crossing of the Wildrose opposition, a move shrewdly executed as though it was a corporate takeover. From those heights, he turned the four-decade Tory dynasty into rubble, a nine-seat rump in an Alberta legislature that was suddenly and unbelievably controlled by Rachel Notley’s NDP.

Prentice steered his governing party into the rocks while offering a platform that voters disliked, though he strongly believed Albertans needed. He had put forth the first remotely credible multi-year policy plan that would begin to wrest Alberta from the energy-revenue roller coaster, and build up its long-neglected nest egg, the Alberta Heritage Savings Trust Fund: raise various taxes for all and trim back some services for all, tackling Alberta’s twin problems with revenues and expenses.

It was a bold dose of tough medicine—the classic sort of budget a government drops after an election, not immediately before. It came soon after oil prices began their descent, but before the job losses started piling up. “At the time of the election, people weren’t prepared to hear that,” says Robin Campbell, Prentice’s finance minister who lost his seat in the Tory wipeout.

The Wildrose howled that there should be no tax hikes, the New Democrats howled there should be no service cuts, and Prentice’s party was squeezed in the middle. Surely, carrying the baggage of a 44-year-old regime brimming with nagging scandal and entitlement problems helped bring him down, but so did a medley of Prentice’s own rhetorical stumbles and his political miscalculations. Prentice’s passing will surely bring the thought to many Albertans’ minds: what if the province suffered through the downturn under his plan, rather than Notley’s?

Until this tragedy, Prentice was remembered mostly bitterly in Alberta for his defeat and subsequent decision to immediately vacate the Calgary seat he had just won again. He suffered the loss mostly in private, re-emerging and granting media interviews only once since—to mourn last November’s car-crash death of Manmeet Bhullar, one of his cabinet ministers and a young lawyer Prentice had mentored—and treated like the son he never had.

In 2014, when Alberta Tories amped up pressure and pleading for Prentice to become their saviour after the party’s acrimonious turfing of Alison Redford, one adviser said approval from Prentice’s wife, Karen, and three daughters would be a key sticking point. Prentice had made a similar agreement when his kids were younger, and aside from an unsuccessful provincial run in 1986—against an NDP candidate—he stayed out of electoral politics himself, and chose to organize and run campaigns instead. That ended with his 2003 bid and third-place finish for the federal Tory leadership, and his 2004 bid for a Conservative seat in Calgary, the first in his decade-long streak of electoral successes.

The son of a northern Ontario coal miner and hockey player, Jim Prentice loved hockey himself as a young man, and worked in the mines near where he grew up in Grande Cache, Alta., to help put himself through university. If politics wasn’t his top skill, he still didn’t practise it meekly: he would sometimes zig when the crowd around him zagged. He didn’t follow the Alberta pack into Reform and Alliance politics in the 1990s, sticking with roles as Red Tory—though he wasn’t opposed enough to stay out of the merged Conservatives, as was the case with Joe Clark. He was one of only a few Conservative MPs who voted for same-sex marriage in 2005. In 2010, he endorsed for re-election his northwest Calgary ward’s decidedly progressive councillor, Druh Farrell—he liked the way she got things done. Later that year, he connected with Naheed Nenshi, and sat in on one of his first meetings as mayor, Nenshi recalled on Oct. 14. “He helped me navigate those tough first few weeks,” Nenshi said in a statement.

From the archives: Jim Prentice: The fixer

This was around the same time the top executives of CIBC also recognized Prentice’s skills in navigation and meeting rooms: they poached him from Harper’s cabinet and named him the bank’s vice-chair and senior executive vice-president. Cabinet ministers often get cushy landings when they leave government, but seldom that cushy a job, with that sort of a title at a top Canadian corporation.

After a couple of years with Prentice in Opposition, Harper too recognized the boardroom prowess and finesse of Prentice, who had practised law mainly in Aboriginal issues and treaty negotiations. In addition to naming Prentice his first Indian Affairs minister—to help mollify band chiefs about to lose the Kelowna Accord with which Paul Martin delighted them—Harper made his fellow Calgarian the chair of his operations committee. He became a sort of chief operating officer of the Harper government, the closest thing that prime minister ever had to a deputy PM. Harper next shuffled Prentice to Industry, an exhaustively important but decidedly unsexy job, and then to Environment, where he moved forward some conservation files but became part of a long line of ministers on that portfolio who brought no breakthrough on climate change action. When Prentice left the ministry for the private sector, Rick Smith of Environmental Defence showed a sort of reverence, wondering if Prentice was merely taking marching orders from on high; another environmental group, the Pembina Institute, joined the email inbox flood of tributes to him the day after his death.

MacKay described Prentice’s “calming effect over discussions” in cabinet. Kenney recalled his “classic Canadian temperament, a kind of reserved confidence.” He was a whirling dervish of policy ideas and reforms in his few months as Alberta premier. His first political slogan as premier conveyed his yen for administrative execution: “Under new management.”

The final contribution from Jim Prentice will be a book he had been writing, likely to come out, posthumously, next year. It’s no political tell-all, no bean-spiller, not even a memoir. His final contribution to the public discourse is all policy, all business. Its working title is Canada, Energy, and the Environment.