Justin Trudeau vs. the anti-carbon tax Avengers

Paul Wells: At the end of 2016, the feds and every province but Saskatchewan agreed to a national carbon plan. Then things started happening.

Power plant, Brandon, MB. (Blickwinkel/Alamy)

Share

I’m as surprised as you are that Brian Pallister just became the most interesting man in Canadian federalism. The Progressive Conservative premier of Manitoba, impossibly tall and lanky, likes to talk like a straight shooter. But his politics are mostly cautious and moderate. In a national political landscape increasingly populated by firebrands—Doug Ford, Maxime Bernier, the new Quebec premier François Legault—there was no particular reason to expect Pallister would stand out.

But a weather vane is a useful tool, and Pallister just turned.

Only a year ago, Manitoba’s environment minister Rochelle Squires announced the province’s plan for reducing carbon emissions. Its centrepiece was a carbon tax: $25 per tonne of emissions every year for five years. It was a clever challenge to the model preferred by Justin Trudeau’s federal government: a tax that would start at $10 per tonne and increase to $50 over five years.

At the end of 2016, the feds and every province except Saskatchewan agreed to a national plan to reduce carbon emissions. This so-called Pan-Canadian Framework declared that if any province didn’t come up with a rigorous plan of its own, Ottawa would impose a carbon tax and send the revenues back to the province. In 2016—that seems so long ago now—the assumption was that most provinces would have their own plan, and the feds would need to intervene in only a few straggler provinces. Ottawa’s interference would carry a light touch: every dollar collected through the carbon tax would go right back to the provincial treasury in that province.

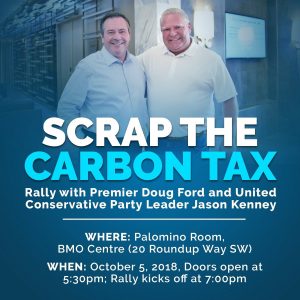

Then a bunch of things started happening. The biggest was that power in Ontario passed from Kathleen Wynne’s Liberals, who had a carbon-reduction strategy the feds would have accepted, to Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservatives, who are fighting the federal plan in court. As is Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe. Ford has formed a carbon-tax-fighting alliance with Moe and the Alberta Opposition Leader Jason Kenney, who’s likely to become that province’s premier after an election next spring. They’re like the Avengers, except their only superpower is to file lawsuits and they don’t—small blessings—wear skin-tight costumes.

But much of the trouble for the federal plan is less spectacular. New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador haven’t filed plans that meet federal expectations. And Manitoba’s plan was a puzzle: it promised to start taxing sooner than the feds would have required, but to max out at a much lower rate. Pallister and his minister had expert opinions that suggested that a faster, gentler approach would actually cut emissions more than the federal plan.

But it was up to the feds to decide whether that was true. Their process for making that decision has been perfectly opaque. But you’d have thought Trudeau was giving a pretty good hint when he visited Winnipeg on Sept. 11. Standing next to Pallister, he tried to make the tallest premier his ally against the country’s other conservative politicians. “To see a leader—indeed a conservative leader—who understands the need to have a concrete plan to fight climate change . . . is something I very much welcome,” Trudeau said. “I wish he would encourage some of the other conservative provinces across the country to recognize that having a plan to fight climate change is something that all Canadians, regardless of where they are on the political spectrum, have the right to expect.”

Trudeau’s rhetorical gambit seems to have backfired. Only three weeks later, Pallister announced he would no longer levy a carbon tax and that he was considering joining the Anti-Tax Avengers in their court challenges to the federal plan. It’s almost as though he didn’t appreciate Trudeau’s attempt to use him as a stick to beat other conservatives.

It’s amazing how fast this whole business has turned against Trudeau. He and his helpers are glibly cheerful about the whole thing. Don’t you see, they say? The rebate cheques for any federal tax will go straight to households, which will make them grateful they are governed by munificent carbon taxers.

READ MORE: Trudeau’s biggest threat after NAFTA—himself

This strikes me as wildly optimistic. Some people will pay more at the pump than they receive in rebates. Some will pay less. Roughly everyone will assume they’re the ones paying too much. When I mentioned my theory to a Trudeau adviser, the answer was: “Wait until you see how big the cheques will be.” Which opens up the possibility of a revenue-negative carbon tax: rebate cheques out of all proportion to the amount collected. This is one way to spend yourself out of a hole. Perhaps somebody will remember where the money to do it comes from.

The feds have revealed so few details of their plans that I find myself wondering whether they picked a fight with Pallister precisely because they were hoping to add Manitoba to the federal rebate gravy train. That would be an odd way to run a country, but these days, what isn’t? It would be helpful to hear, at intervals, from the federal environment minister, Catherine McKenna, or the new intergovernmental minister, Dominic LeBlanc. But the detailed speeches to chambers of commerce or Canadian Clubs you might expect from one or the other have not been delivered. The ministerial op-eds haven’t been written. If Trudeau and company are not making this all up as they go along, they are doing a very good job of seeming to.