Levon Helm sang like a great character actor acts

The Band’s brand of rock was folksy, but not in the confessional singer-songwriter vein

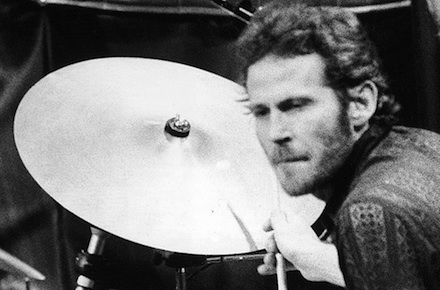

FILE – In this Nov. 27, 1976 file photo, Levon Helm, of The Band, playes drums at the band’s final live performance at Winterland Auditorium in San Francisco. Helm, who was in the final stages of his battle with cancer, died Thursday, April 19, 2012 in New York. He was 71. He was a key member of The Band and lent his distinctive Southern voice to classics like “The Weight” and “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” (AP Photo/John Storey, file)

Share

Levon Helm, who died yesterday, lent his wonderful voice to a lot of great songs, but arguably his finest moment comes when he lets loose the famous first line of Robbie Robertson’s “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” “Virgil Caine is the name and I served on the Danville train,” Helm sings, “Till Stoneman’s cavalry came and tore up the tracks again.” Who hearing him doesn’t believe for a moment that he’s drawing on fresh memory of the Civil War?

Levon Helm, who died yesterday, lent his wonderful voice to a lot of great songs, but arguably his finest moment comes when he lets loose the famous first line of Robbie Robertson’s “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” “Virgil Caine is the name and I served on the Danville train,” Helm sings, “Till Stoneman’s cavalry came and tore up the tracks again.” Who hearing him doesn’t believe for a moment that he’s drawing on fresh memory of the Civil War?

In that sense, Helm’s gift was as much as an actor as a singer. Robertson gave him lyrics that worked as dramatic set pieces. The Band’s brand of rock was folksy, but not in the confessional singer-songwriter vein. In the group’s best songs the singers, usually Helm or the late Richard Manuel, had to embody a character, rather than reveal themselves directly in the style of, say, James Taylor or Joni Mitchell. So Helm, son of an Arkansas cotton farmer, was called on to put the right accent on a Canadian songwriter’s elegiac imagining of the South.

It’s been observed that Robertson’s lyrics can be surreal, and I guess that’s true in places. But there’s straight-up realism of many of the songs—including “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down”—and snippets of something that feels closer to magic realism in others—like the devil’s casual appearance in “The Weight.” Around the time the Band was coming to prominence, and the voice of Levon Helm lodging itself in our popular consciousness, there seemed to be a need for stories about sad, bypassed places where impossible things just happened and modernity was an unreliable rumour.

Only a few months after “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” was released on the LP simply entitled The Band, the English translation of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude appeared, and the New York Times reviewer marveled at how Garcia Marquez “seems to be letting his people half-dream and half-remember their own story.” That would be a good description of what Robertson lets Virgil Caine do, and Helm made him a palpable presence in the grooves on the vinyl, just as he did the unnamed, but equally individual, narrators in songs like “The Weight,” “Yazoo Street Scandal” and “Don’t Ya Tell Henry.”

Helm was a good actor in the usual sense of the word, too, as evidenced by his character-role turn in the Loretta Lynn biopic Coal Miner’s Daughter. His movie credits feature in obituaries as a minor element, and that’s as it should be. But I think noting that acting sideline nudges us toward a better understanding of what is so good about what he leaves us as a singer of stories.