Quebec’s political mood swings

Philippe J. Fournier: The past decade of Quebec politics has shown voters to be highly volatile. None of the parties can afford to play defence.

Blanchet, leader of the Bloc Quebecois party, left, with a volunteer at a community food bank (Christinne Muschi/Bloomberg/Getty Images)

Share

When Quebecers went to the polls in the October 2018 provincial election, they elected 74 candidates running for François Legault’s Coalition Avenir Quebec (CAQ)—a party that was created in 2011 and finished in third place in its first two general elections.

In 2018, the CAQ received a little over a million and a half votes, winning the popular vote by more than 12 points over the incumbent Quebec Liberal Party and more than double the number of votes cast for the Parti Québécois. For the first time in 50 years, neither the Parti Québécois nor the Quebec Liberals are at the helm of the National Assembly.

This major paradigm shift did not happen in the blink of an eye, however. There have been significant fluctuations and mood swings in Quebec’s electorate in the past decade. Case in point: in the last three provincial elections in Quebec (2012, 2014 and 2018), three different parties—and premiers—were voted in and out of power.

READ MORE: Wells: The missing ingredient in this federal election

In these three general elections, no fewer than three party leaders, including two incumbent premiers, couldn’t even win re-election in their respective electoral districts. After months of civil unrest and a massive student strike, Jean Charest was defeated in Sherbrooke in 2012; Pauline Marois, who had been in power for only 18 months, lost in Charlevoix in 2014 against an unknown Liberal challenger; and in 2018, Parti Québécois leader Jean-François Lisée lost his re-election bid in Rosemont, which had once been an unshakeable PQ stronghold in the heart of Montreal.

I did a little research to find similar patterns in Canada: had there ever been any three consecutive elections in which three different parties, running a full slate of candidates in each election, had won power in Canada? The only other case I could find was the Ontario elections of 1987, 1990 and 1995, when Ontarians went from the Liberals of David Peterson to Bob Rae’s NDP to Mike Harris’s Tories.

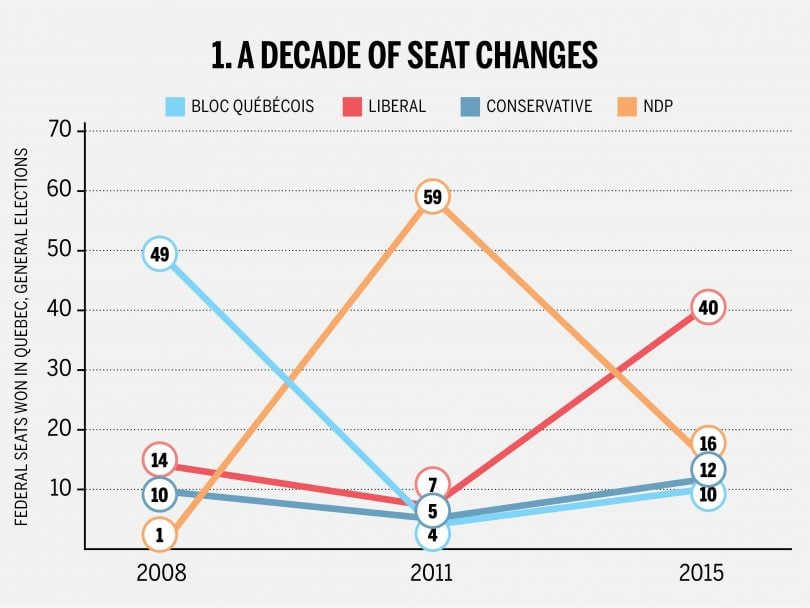

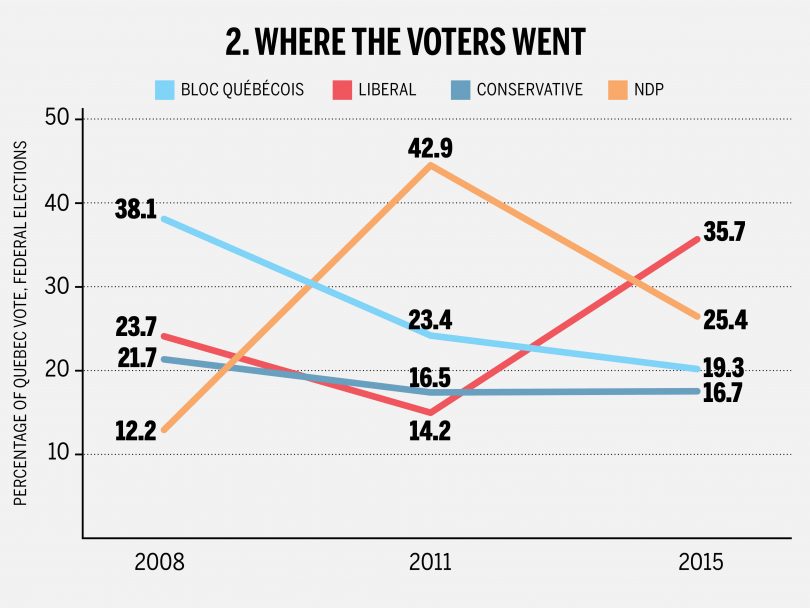

On the federal scene, Quebec voters have also been volatile in the past decade. In 2008, Stephen Harper’s majority bid was halted by Gilles Duceppe’s Bloc Québécois, which won 38 per cent of the vote in the province and captured 49 of Quebec’s 75 federal seats. Three years later, 43 per cent of Quebec voters flocked to Jack Layton’s NDP—the orange wave that sent a shocking 59 NDP MPs from the province to the House of Commons. The 2011 federal election produced the worst result for the Bloc Québécois in its history (four seats) and the worst Liberal result in Quebec (seven seats) since the 1988 Mulroney victory. Finally, four years later, 35 per cent of Quebec voters chose Justin Trudeau’s Liberals and sent 40 Liberal MPs to the House of Commons, the highest total in Quebec for the LPC since Pierre Trudeau’s last victory in 1980.

On the federal scene, Quebec voters have also been volatile in the past decade. In 2008, Stephen Harper’s majority bid was halted by Gilles Duceppe’s Bloc Québécois, which won 38 per cent of the vote in the province and captured 49 of Quebec’s 75 federal seats. Three years later, 43 per cent of Quebec voters flocked to Jack Layton’s NDP—the orange wave that sent a shocking 59 NDP MPs from the province to the House of Commons. The 2011 federal election produced the worst result for the Bloc Québécois in its history (four seats) and the worst Liberal result in Quebec (seven seats) since the 1988 Mulroney victory. Finally, four years later, 35 per cent of Quebec voters chose Justin Trudeau’s Liberals and sent 40 Liberal MPs to the House of Commons, the highest total in Quebec for the LPC since Pierre Trudeau’s last victory in 1980.

Once again: three consecutive elections, three different winners in the province of Quebec. (See charts 1 and 2.)

Some would qualify the Quebec electorate as “volatile,” but others would say “dissatisfied.” I believe these two epithets are not mutually exclusive.

Some would qualify the Quebec electorate as “volatile,” but others would say “dissatisfied.” I believe these two epithets are not mutually exclusive.

It was therefore not so surprising to see Andrew Scheer launch his campaign in Trois-Rivières, a city of 150,000 in the heart of the Mauricie region of Quebec, which was swept by Legault’s CAQ last year. Mauricie voters have not elected PQ MNAs or Bloc MPs since the 2012 Quebec election, and it’s those small-c conservative voters that Conservatives must flirt with if they hope to make net gains in Quebec.

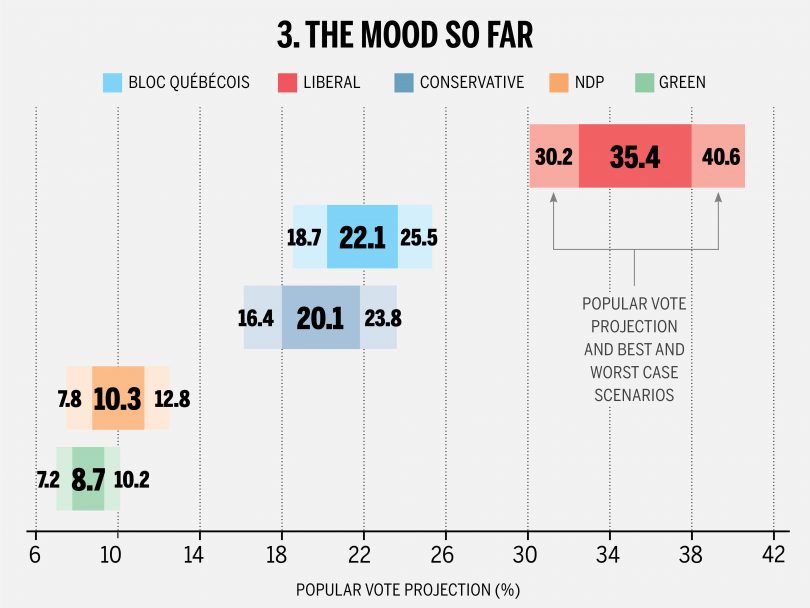

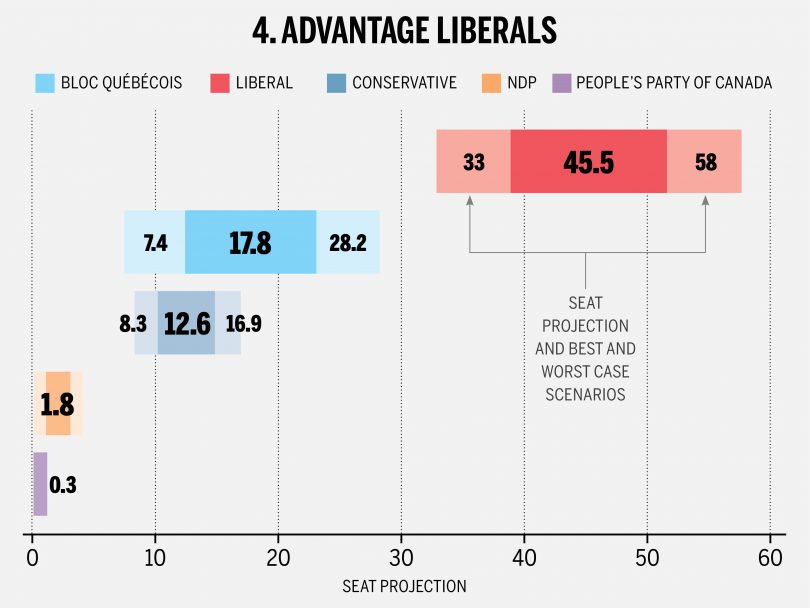

In 2015, Harper’s Conservatives won only 16.7 per cent of the Quebec vote and, as of this writing, the party is polling above 20 per cent in the province, so the Conservatives have every reason to be hopeful. (See charts 3 and 4.)

In the first days of the campaign—and to the surprise of some observers—Jagmeet Singh spent considerable time in Quebec: he visited Sherbrooke, travelled through the Eastern Townships toward the Montérégie area (the south shore of Montreal) to visit several of his remaining Quebec MPs. He then travelled all the way to rural Mauricie for the Festival Western de Saint-Tite. According to current projections, Singh is facing long odds in Quebec; the NDP is polling in single digits and at risk of being swept out of the province altogether. Yet Singh knows Quebec has sent more NDP MPs to Ottawa than any other province in the last decade.

In the first days of the campaign—and to the surprise of some observers—Jagmeet Singh spent considerable time in Quebec: he visited Sherbrooke, travelled through the Eastern Townships toward the Montérégie area (the south shore of Montreal) to visit several of his remaining Quebec MPs. He then travelled all the way to rural Mauricie for the Festival Western de Saint-Tite. According to current projections, Singh is facing long odds in Quebec; the NDP is polling in single digits and at risk of being swept out of the province altogether. Yet Singh knows Quebec has sent more NDP MPs to Ottawa than any other province in the last decade.

Meanwhile, Justin Trudeau travelled to the Laurentians and Lanaudière, two regions north of Montreal that have not necessarily been kind to the Liberal brand in several years. The Quebec Liberals won a majority at the National Assembly in 2014 without winning a single seat from those regions; in the 2015 federal election, Liberal candidate David de Burgh Graham won the district of Laurentides-Labelle thanks to a serendipitously split vote—Graham received only 32 per cent of the vote, but it was enough to beat the NDP incumbent and BQ candidate. He was the only federal Liberal MP elected in the area.

Meanwhile, Justin Trudeau travelled to the Laurentians and Lanaudière, two regions north of Montreal that have not necessarily been kind to the Liberal brand in several years. The Quebec Liberals won a majority at the National Assembly in 2014 without winning a single seat from those regions; in the 2015 federal election, Liberal candidate David de Burgh Graham won the district of Laurentides-Labelle thanks to a serendipitously split vote—Graham received only 32 per cent of the vote, but it was enough to beat the NDP incumbent and BQ candidate. He was the only federal Liberal MP elected in the area.

The fact that Justin Trudeau and his team decided to spend valuable campaign time in these districts shows the Liberal party is not merely playing defence in the province.

As for the Bloc, Yves-François Blanchet believes the sovereignty movement “is due for some good news” after several consecutive elections of declining numbers both for the PQ and the Bloc. If recent history is any indication, he should know that Quebec voters can turn on a dime and change their minds during weeks of a campaign. Politicians of any stripe should never take the Quebec voter for granted.

This article appears in print in the November 2019 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “The most volatile voters.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.