The Conservative Party’s Kevin O’Leary factor

The brash businessman nicknamed ‘Mr. Wonderful’ is tops in the polls to lead the Conservative Party of Canada. But why would he want to?

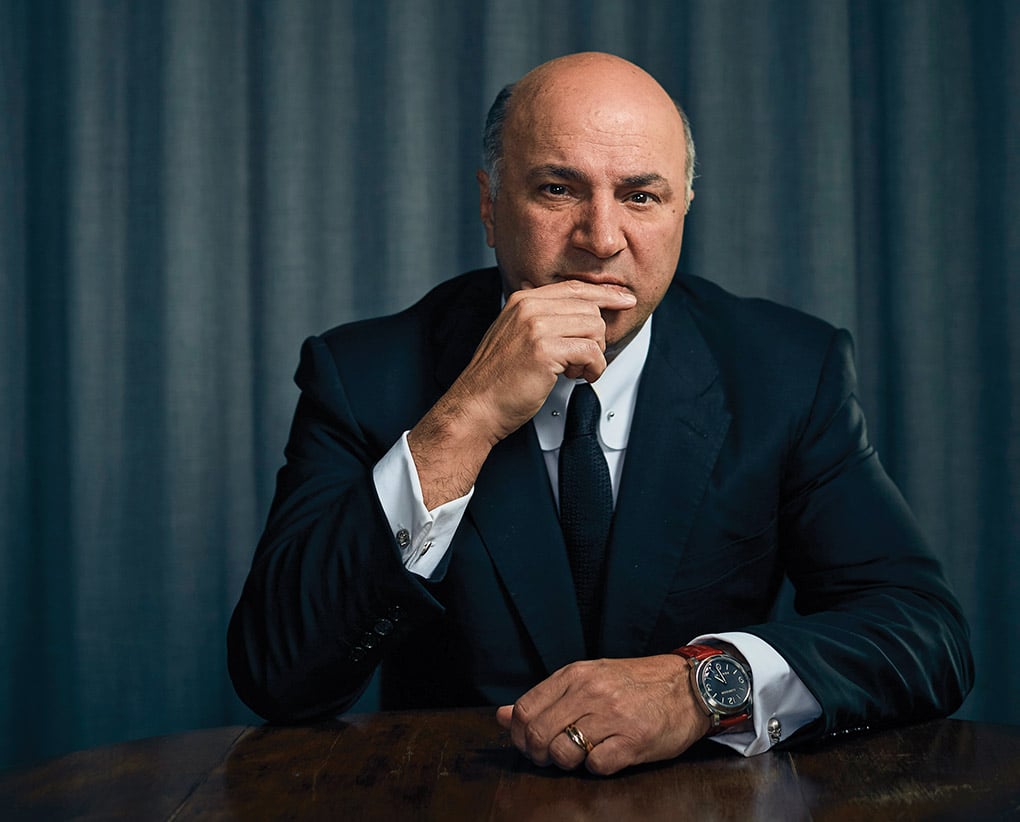

Kevin O’Leary poses for a portrait at his hotel in Miami, January 19th, 2016. (Photograph by Ryan Stone/Novus Select)

Share

Kevin O’Leary entered the Conservative leadership race on Jan. 18, 2017. Check out Jonathon Gatehouse’s in-depth profile from 2016, long before O’Leary took the plunge.

Kevin O’Leary’s stalker is occupying a strategic position by the elevators. Plump and pleasant-looking, with dyed-blond hair and a pink T-shirt, she has lain in wait for 45 minutes in the upstairs corridor of a mostly empty office complex in suburban New Jersey. Signs she has whipped off on the boss’s printer are taped all over the walls. “Welcome Mr. Wonderful!” reads one. “Come this way and say hi to your fans,” begs another.

O’Leary has been busy playing salesman on this afternoon, visiting area brokerages to pitch an investment fund he’s fronting, but he’s dressed just the same as when he’s on TV. The wardrobe coordinator for Shark Tank hit upon the slightly menacing look—black suit and tie, Prada shoes, and a custom-made white shirt with a collar bar and death-head cufflinks—in the show’s third season, and it’s all he’s worn in the five years since. O’Leary now has 22 identical suits from the New York City tailor he shares with President Obama, and recently ordered two more. It makes travelling simple between his homes in Boston, Toronto and Geneva, and the places he rents in Florida and L.A. And it renders him instantly recognizable.

“You’re the guy from TV!” exclaims a man with a broken foot and Red Sox cap, smoking outside of a doctor’s office in Boston. “Yo, Mr. Wonderful!” a gent in a suit and tie calls out from the sidewalk in Greenwich Village. People nudge each other and point as O’Leary walks through airports. In restaurants, they approach his table and politely request a photo. “I watch you every Friday night, and I feel like I know you,” the Jersey woman explains when he reaches the elevator stakeout. O’Leary looks at his watch, then follows her down the hall to the mortgage firm where she works to shake some hands, chat, and pose for a few dozen selfies. There’s a reason why he chronically runs late.

Canadians tend to think of the soon-to-be 62-year-old businessman as one of our homegrown, quasi-celebrities; that loudmouth guy from CBC News Network and Dragons’ Den, and more recently, CTV News Channel. But O’Leary has become a bona fide American star since signing on as one of ABC’s “sharks” in 2009. The reality show, which lets struggling business people pitch ideas and inventions to a panel of rich investors, is a ratings champ, dominating its prime-time Friday night slot, and capturing close to 10 million viewers a week, once reruns are factored in. It has spawned a spin-off, Beyond the Tank. O’Leary also has a thrice-weekly gig as a business commentator on CNBC, and appears regularly on Good Morning America and CNN. He even has a dedicated segment on shopping channel QVC, Mr. Wonderful’s Wonderful Discoveries. A few weeks ago, he performed a marathon 12-hour stint hawking his O’Leary Fine Wines, made by a California vintner. The entire production order—294,000 bottles—sold out, grossing US$2.97 million.

Which is all to say that Kevin O’Leary seems a little too famous, too busy, and perhaps too entrepreneurial to even be considering a run for the leadership of the staid Conservative Party of Canada. Yet he’s more than happy to fuel such speculation. A January talk-radio tirade about Rachel Notley and the Alberta NDP—“She’s 1,000 feet underwater. She drowned six months ago. She’s a corpse. She’s incompetent,” he said—somehow morphed into a sure-I-can-do-better round of media interviews. O’Leary isn’t a member of the federal party, and he doesn’t have a team or a timeline. But he travelled to Ottawa in late February to suck up all the oxygen at a Tory gathering, and plans to do the same at the Conservative policy convention in Vancouver this weekend. Maybe it’s just the spillover effect from the unlikely political success of another U.S. reality-TV star, but an O’Leary candidacy can’t be dismissed out of hand. Opinion polls suggest he has better name recognition, and more support—27 per cent versus Peter MacKay’s 23 per cent in the latest Forum Research survey of likely Tory voters—than any other potential leader. “I think Canadians know me pretty well. Many don’t like me, but they trust me,” says O’Leary. “I don’t have to do things the traditional way.”

Mr. Wonderful—a nickname bestowed as an insult by another shark in the show’s first season—gets a lot of corporate speaking requests these days. He usually takes on two or three such gigs a month, at a fee of US$60,000-$75,000, depending on the duration. The deciding factor is always whether it’s a worthwhile networking opportunity.

On a late April morning, O’Leary takes the stage at a Boston hotel to deliver the keynote address to a room full of pension fund managers attending a conference organized by a real estate investment firm. He’s wearing the suit. The presentation begins with a slick, self-narrated video about his life and business accomplishments that culminates with a rising-drone shot of him shredding on a custom-made Fender electric guitar on the deck of his giant Muskoka cottage. The spiel that follows is mostly about Shark Tank, and the lessons learned from the 32 businesses he has invested in via the show. During the Q&A that follows, an audience member asks how being on a hit series has changed his life. O’Leary shares an anecdote about being confronted by an angry fan while using a urinal at Boston’s Logan International Airport. Mrs. Wonderful—his wife, Linda—is waiting outside. “You know who’s in there? That asshole from Shark Tank,” the unhappy viewer tells her, as he stalks past. “I know,” she replies.

The self-deprecating story gets a nice laugh. Just the way it did when he used to tell it to Canadian audiences—back when it happened at Toronto’s Pearson airport, and the show in question was Dragons’ Den. Of course, there’s no law against recycling jokes. In politics, they call it a stump speech.

The Manning Centre Conference in Ottawa, an annual gathering of right-wing activists, think tankers and politicians, brands itself, without apparent irony, as “the Conservative Woodstock.” By that analogy then, its gaggles of pimply young Tories stand in for hippies—favouring free markets instead of free love—and Kevin O’Leary is Jimi Hendrix, playing a Stratocaster with his teeth. At the last session in February he was the undisputed star, mobbed by picture-seekers, trailed by a pack of reporters and cameras, and feted everywhere he went.

It all brings Donald Trump to mind. When the comparison is raised, O’Leary allows that they’re both good businessmen, and owe their U.S. TV success to the same man, Mark Burnett—the executive producer of The Apprentice and Shark Tank—but says that’s where the similarities end. The Montreal-born son of an Irishman and a Lebanese-Canadian woman isn’t interested in building walls. And he isn’t shy about telling his prospective party that niqab bans and “barbaric cultural practices” snitch lines are why it lost the last election. “It’s a huge mistake to think you can ever divide Canadians on racial issues,” he said, repeatedly, in Ottawa. “Stephen Harper tainted the Conservative brand when he did that.”

O’Leary has, however, absorbed some lessons from Trump, Rob Ford and other populists about the virtue of having a simple theme and sticking to it. “All I give a s–t about is jobs, jobs, jobs,” he says. His quote-ready rants about Rachel Notley and Justin Trudeau always have the same underlying thesis: that government regulations and interventions won’t help grow a struggling economy. O’Leary likes to suggest that anyone who wants to run the country should have at least two years experience making payroll for at least a $5-million-a-year business, as he does. Even criticism over his inability to speak French—Maxime Bernier, a declared rival for the leadership, calls him a “tourist” in both Quebec and the party—gets countered by his entrepreneurial credentials. “The world doesn’t care anymore what language you speak, unless it’s the language of job creation and economic growth,” says O’Leary. Ask about pressing global issues like climate change, and he’ll tell you it’s real, but “nowhere near the top” of his short, economy-driven list. The message is so single-track it can be comedic at times. During a question and answer session with Manning Centre conference “VIPs” (read youthful, former Hill staffers in ill-fitting suits), someone asks O’Leary about his mother’s influence on his life. His response begins with a well-worn story of her banking advice—“always spend the interest, never the capital”—then quickly morphs into a lecture about the need for new oil pipelines and fewer restrictions on big telecoms.

O’Leary offers little policy depth, and no political pedigree, but his TV career has clearly provided him with some transferable skills. He isn’t just comfortable in front of the camera, he’s a commanding presence. The sound bites come fast and furious. (CNBC, he explains, demands at least four of them per minute, none lengthier than 14.5 seconds, the attention-span limit for video clips on Twitter and Instagram.) His personal branding as a teller of “cold, hard, truth”—the phrase features in the titles of all three of his bestselling financial-advice books—meshes nicely with the Tories’ core, get-off-my-lawn demographic, even if his reputation as a business wiz has taken some recent hits. Last fall, he sold his eponymous mutual fund business to W. Brett Wilson, a former Dragons’ Den co-star, after investors started pulling their money en masse because of poor performance.

O’Leary does possess the kind of ruthless streak that might serve a politician well. At the conference, he keeps Pierre Poilievre, the former minister of employment and social development, waiting around in a lobby for a promised meeting, showing up almost a half-hour late with some surprise guests—a reporter and photographer. The five-term Conservative MP looks like he’s considering digging an escape tunnel as O’Leary lights into the MP’s former boss, expounding in detail and on the record about how Harper squandered a chance for another majority. And when Poilievre expresses his belief that the party needs a leader with a “true conservative agenda” who will resist pressure to move toward the centre, O’Leary is almost cruelly dismissive. “I’m not going to brand any of these policies as conservative,” he says. “Voters just don’t give a s–t.”

But Mr. Wonderful’s greatest strength might be his ability to play hard to get. With the leadership vote set for May 2017, still a year away, he says he sees no reason to commit anytime soon. He’s keeping his options almost absurdly open, musing that he might take a run at Justin Trudeau’s job instead. “He’s the wrong guy at the wrong time,” he says. “In three years, I think the Liberals will be looking for a leader too.”

The main ballroom at the downtown Ottawa Conference Centre is packed for the session entitled “If I run, here’s how I’d do it.” The first contender to take the stage is Michael Chong, the Tory MP for the Ontario riding of Wellington–Halton Hills. His 15-minute presentation is heavy on family history, weaving the stories of his Hong Kong-born father and Dutch-immigrant mother, and their gratitude to the Canadian troops that fought to liberate them both in the Second World War. There are pictures of his dad working as a lumberjack in northern B.C. to pay his tuition at medical school. When the 44-year-old Chong shows a slide of his own wife and kids, he switches into French to explain how the three boys are enrolled in an immersion program in his hometown of Fergus. It’s a compelling, media-friendly sort of package, brimming with optimism. The Conservatives in the room seem indifferent at best. Chong’s pitch that the party remake itself as a protector of the economically vulnerable is greeted with stony silence. There’s scattered applause for a pledge to preserve the environment. It’s only his call for a simpler, flatter personal tax regime that elicits any real enthusiasm.

When it’s his turn, O’Leary takes the stage in costume and struts confidently back and forth, wielding a hand-held mic like a practised entertainer. He describes a Canada that is economically broken and drowning in government debt. He tears yet another strip off Rachel Notley, trashes the Trudeau budget, and pledges to hold a binding, national referendum on the building of new oil pipelines. “I’m sick of seeing my money wasted. I’m really pissed off,” he says, as Preston Manning, the event’s MC, giggles in embarrassment. “No more stupid deals!” Someone in the crowd shouts “Amen” like it’s a tent revival. When O’Leary finally leaves the stage, running well past his allotted time, the applause is warm and sustained.

Nature abhors a vacuum. So does the media. And Kevin O’Leary knows how to take full advantage.

The hired black car is crawling through Manhattan’s morning traffic, and O’Leary is multitasking. First, responding to some of the 10,000 emails he receives each month, while he answers questions, then taking photos of the dozens of business cards people have given him and adding searchable notes about when, where, and what they discussed. As the limo nears its destination, a Tribeca restaurant, he pulls out an electric razor for a quick touch-up, then applies some makeup to the top of his bald head. “There might be some local TV,” O’Leary explains.

As it turns out, it’s mostly wedding bloggers who have turned out for the media breakfast promoting Honeyfund—a crowdfunding site for honeymoons that is one of his Shark Tank companies. O’Leary gives a short speech about how his best investments invariably turn out to be women-led firms because they manage time better and work smarter. It’s a message that will be repeated in a season-ending Beyond the Tank special on Honeyfund, hosted by Ariana Huffington, and then showcased on Huffington Post in a section dedicated to female entrepreneurs. During the show, O’Leary’s social media specialist will pump out a stream of tweets and Instagram posts timed to commercial breaks to drive even more eyeballs to Honeyfund.com. “I wasn’t hip to this two years ago, but now it’s the whole ball game,” he says. “We can reach millions of new customers with zero acquisition cost.”

The Shark Tank effect can be considerable. Sara Margulis, the co-founder and CEO of Honeyfund, says the night her company debuted on the show she watched her web traffic crest in waves as it aired across the U.S. time zones. Transactions on the site have quadrupled since the 2014 episode. “Kevin is extremely well connected to the media and spends a lot of time talking about us,” says Margulis. “It really drives things.”

There was once another side to O’Leary. He had a beard and a mop of curly locks and studied environmental science at the University of Waterloo. But it receded along with his hairline. After obtaining an M.B.A. at Western, his first business venture was in television at the beginning of the 1980s, as the co-founder of a company that made shows like Don Cherry’s Grapevine. A couple of years later, he took a detour into computers, starting SoftKey Software Products from his Toronto basement. The company grew rapidly, gobbling up competitors in the educational software market, and O’Leary relocated its headquarters to Boston. By 1996, after a hostile takeover of the Learning Company (O’Leary’s company took on their name) it was the biggest schoolkid-focused firm in the world, with 3,000 employees and more than $800 million a year in revenues.

David Patrick, SoftKey’s former head of worldwide sales, now the chairman of Apperian, a Boston firm that manages and supports mobile apps, says O’Leary had a keen business mind and a ferocious capacity for work. “Kevin was the marketing czar, the product guy, the visionary for distribution and retail,” he says. “He was just like he is on his show. Very decisive, very smart, and quick to drop something that was a dog.”

In 1998, the Learning Company was purchased by Mattel, the toy-maker, in an all-stock deal worth US$3.8 billion. O’Leary was fired six months later, amid soaring losses and a tumbling share price. Businessweek magazine rates the takeover as one of the “worst deals of all time,” and it cost Mattel CEO Jill Barad her job, too. What was left of TLC was sold to another firm for $27.3 million in 2000.

But O’Leary and the other SoftKey principals all made good money on the deal and remain close to this day, sharing a massive wine cellar in Cambridge, Mass., and getting together with their wives and families four or five times a year. The July 4 gathering always happens in Nantucket. Last summer, it featured the surprise wedding of Patrick’s son, Matt, and his bride, Erica. The pair came up with the idea of asking O’Leary to obtain a special one-day justice of the peace licence and marry them. He took it a few steps further, bringing in a bunch of his Shark Tank firms—Honeyfund, a cupcake baker, and a company that makes souvenir bottle openers from .50-calibre bullets—to support the festivities. Then he filmed it for an episode that aired last October. “It’s Kevin. Nobody was surprised,” Patrick says with a laugh. “That’s the marketing mind that never sleeps.”

O’Leary does have some outside interests. Along with the 40 or so guitars he owns, he collects fountain pens and luxury watches—always with a red band, as part of his branded look. He’s a keen photographer, carrying a camera with him in his satchel wherever he goes, and he recently had gallery exhibitions in Miami and New York where his pictures were sold for charity. He’s big into modern art, with works by Andy Warhol, Yigal Ozeri and others decorating his various homes and offices. During the Ottawa trip, O’Leary ducked into the Château Laurier to retrieve his suitcase and ended up impulse-buying an Inuit stone carving for $1,500 from a gallery in the lobby. “When you see something you like, you have to seize the moment,” he says.

He travels almost every day of the week, but makes a point of bringing his family—Linda, daughter Savannah, 23, who lives in New York, and son Trevor, 19, a McGill University student—together every weekend. Sometimes they’ll fly to Geneva on a Friday night just to have Saturday dinner with his Swiss stepfather, George, now in his mid-80s, then return to North America on Sunday. O’Leary and Linda fly business class, and the kids in coach. “Why should I pay for their first-class seats?” he says. “They’ve got to get motivated and learn there’s no free lunch.”

He wasn’t always such an involved parent. Part of his standard patter for audiences is a warning that building a successful business means sacrificing years of home life in exchange for financial security further down the road. Linda, who met him 33 years ago when she was a university student working behind the reception desk at a Toronto squash club, says his work always came first. “I did the house and raised the kids, 100 per cent,” she says. “He made the financial decisions.” Linda takes the credit—or blame—for her husband’s television career. “I was watching CNBC one morning and I told him, ‘You could do a better job than these guys.’ ” In 2003, O’Leary browbeat an executive from ROB-TV (now the Business News Network) in Toronto into letting him audition, and hasn’t left the small-screen since.

Amanda Lang, who played good cop to his bad for 11 years, first on BNN’s Squeeze Play, then CBC News Network’s The Lang & O’Leary Exchange, says he has a natural instinct for what works on a panel show. Viewers connect with O’Leary’s contrarian persona because it’s a real, if slightly dialled-up, version of his actual self. “He’s like a little kid,” she says. “He pushes a button and something happens and he likes it.” Lang, now with Bloomberg TV, has doubts about whether her former co-host is cut out for the drab, door-knocking, ribbon-cutting reality of Canadian politics. But he could easily adapt to its cut-and-thrust debates and battles. “He’s got the thickest skin you’ve ever seen,” she says. “He’s completely confident. Even if it’s sometimes misplaced.”

Lang and O’Leary weren’t particularly close. They socialized outside of the studio maybe a handful of times over their decade working together. But she says he can be more sensitive and reflective than he appears. Kevin and Linda separated for a couple of years around 2010, and he behaved like a typical, middle-aged “jackass,” says Lang. Then one night, they went out for drinks after taping an Air Farce New Year’s special and O’Leary confessed that he’d made a mistake. “ ‘She’s my best friend and I miss her,’ he said. It was the most mature thing I ever heard him say,” Lang recalls. Shortly after, he reconciled with Linda. “So, he’s got depth. He wasn’t prepared to do the 23-year-old thing forever,” says Lang.

Don Allan, a Toronto film and video director who has been friends with O’Leary since the early ’80s, says he’s more generous and progressive than he’s willing to let on. “He plays a part on TV where’s he’s a prick,” says Allan. “But it’s a shtick. He’s like Marilyn Manson, or Alice Cooper. Some of it’s for shock value.” Despite appearances, O’Leary doesn’t have a big ego, says Allan. And he tires of all the attention. Sometimes when they go out for dinner in Toronto, he ditches the trademark suit in favour of jeans and a ball cap to go unnoticed. Allan doesn’t think O’Leary is really serious about moving to Ottawa. “He hates winter, for one thing,” he says. “And Kevin can have an influence on Canadian politics without even running.”

Those doubts are echoed by O’Leary’s boss, Clay Newbill, the showrunner and executive producer of Shark Tank. “I don’t want to burst the bubble, but from the conversations that I’ve had with him, I don’t know that he really has an interest,” he says. It took a few years for the show to find its audience, but now there’s an almost magical connection, says Newbill. And O’Leary, the dark villain who always sits at the centre of the set, is the straw that stirs the drink. “Kevin is the one that seems to cross all the boundaries and resonate with all the viewers,” says Newbill. “He’s the Simon Cowell of our team.” ABC has renewed Shark Tank for an eighth season and taping begins next month in L.A. But Newbill is thinking much longer term. “This is a show that could go for 20 seasons or more.”

It’s difficult, really, to comprehend why O’Leary would want to trade what he has for the unglamorous job of leader of the official Opposition and a steep cut in pay. He won’t talk about his net worth, other than to say that the estimates—mostly in the $300 million to $400 million range—are wrong. “I just need to maintain my money, not grow it. I could put everything in a blind trust,” says O’Leary.

Still, his name and television presence are the chief marketing points for the O’Shares Investments ETF (exchange-traded fund) he is busily promoting across the United States right now, promising the same five per cent a year yield he and his team failed to deliver in Canada, via a similar strategy of low-volatility, high-dividend stocks. At present, it has US$180 million under management, but O’Leary says it needs to grow to around $1 billion to be a sustainable player. Maybe it wouldn’t matter for the fund, or any of his business interests. “The Prime Minister’s Office is a pretty good platform too,” O’Leary notes.

It’s toward the end of a long day when O’Leary pulls up to a steak house nestled amongst the big box stores in Waltham, Mass., a Boston suburb. Inside, in a room decorated with paintings of fox-hunting English gentlemen, a dozen Morgan Stanley employees are waiting to endure his ETF pitch and pose with Mr. Wonderful for a photo that they invariably explain is “for my wife.” One guy in the room manages $450 million of other people’s money, but all he really wants to talk to O’Leary about is his wife’s small company that makes hassocks with college team colours and logos—an investment opportunity that might be a perfect meal for the “sharks.”

“I intend to be in this business for a long time,” O’Leary tells the audience during his spiel. “I’ve got four other index funds I’m working on.”

Afterwards, he stands in the centre of a circle of young brokers with a glass of pinot noir in his hand. Outside, the sun is setting over I-95. They’re peppering him with questions about the show, and comparing notes on their favourite episodes. O’Leary lets slip that he recently signed a new two-year contract. Season 9 of Shark Tank would start filming in June 2017. That’s one month after the convention to choose a new leader for the Conservative Party of Canada.