The noise and the stakes

Paul Wells: The maddening choice comes down to this: a government that is fiscally responsible or one that takes climate action seriously. You can’t have both.

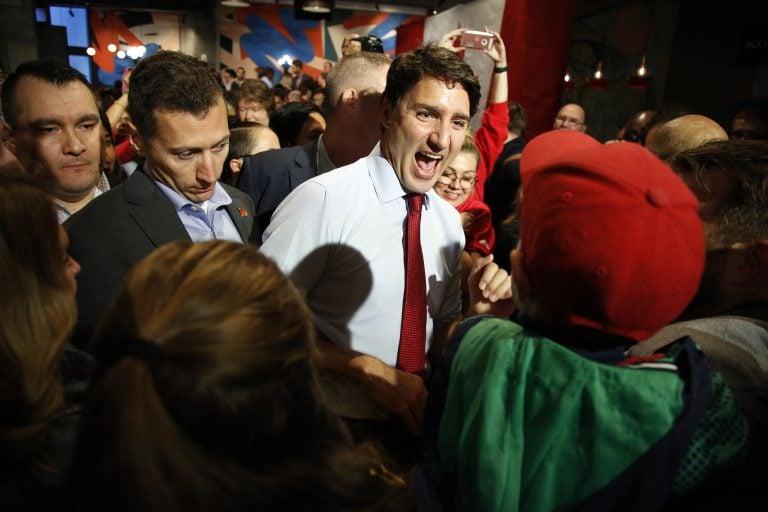

Trudeau greets supporters during a rally in Ottawa on Oct. 11, 2019 (David Kawai/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Share

Much of what’s happened in this miserable campaign has been healthy. If the seat projections from our friend Philippe J. Fournier are accurate, the two largest parties have both lost support since the campaign began. And the worst part of the campaign was the nine days that began with the TVA French debate on Oct. 2 and ended with the two commission-sanctioned debates on Oct. 7 and 10.

Canadians looked at the leaders on offer and said, “Huh. Hmm. Who else do you have?” It’s not a stampede of voters to other parties. More of a trickle. But this impulse is an expression of wisdom.

Justin Trudeau’s blackface controversy did not hurt the Liberals’ prospects nearly as badly as the spectacle of Trudeau’s white face on TV explaining his plans for the country. But Andrew Scheer’s Conservatives lost support over the same period too. The more Canadians see of them, the less eager they are to buy what they’re selling. Now, somebody’s got to win this thing: either Trudeau or Scheer will be prime minister after Monday (short of something truly weird happening). But let’s not pretend afterward that whoever wins that coin toss was a strategic genius all along. They can’t both lose, is all.

I’ll get past this plague-on-both-their-houses line in a minute. And I’ll happily grant that the NDP’s modest but rapid recovery in the polls, like the Bloc Québécois’s in Quebec, is driven by the real qualities of a leader whose abilities a lot of people had discounted. But it’s not the Bloc or the NDP that will form the next government. And despite themselves, the Liberals and Conservatives have managed to reveal real policy differences that should drive voters’ choices.

But I’ll say it again: it’s a healthy thing when the dark arts of the campaign masterminds succeed only in driving down voter support. I think it’s that campaigns have become so obsessed with a few swing ridings and demographic groups that they forget to check whether they’re saying anything that makes sense for a country.

READ MORE: An expert guide to minority scenarios

For the Liberals in particular, who have staked everything for a year on protecting Justin Trudeau without regard to what he and his staff actually say and do, a wholesale post-election shakeup is past due. When they were busy tossing former cabinet ministers overboard this spring, Liberals liked to tell one another, “Politics is a team sport.” Fine. Team owners fire coaches and general managers who blow leads.

Low marks for style, then. But governing is also about big choices. The Conservatives and Liberals have put very different priorities on the table for voters.

To me the central distinguishing proposal of Andrew Scheer’s Conservatives is their promise to balance the federal budget in five years. It won’t be easy. Kevin Page, the former parliamentary budget officer who runs the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa, suggests just how hard it will be in the report card his shop released on the Conservatives’ platform.

Scheer is pledging to hold transfers to the provinces and to individuals steady, while implementing substantial tax cuts. That means he’d need to cut deeply into program spending to hit his target. “Spending reductions target areas including… infrastructure, national defence and security, natural resources, environment, and agriculture,” Page writes. In conversation, he told me the scale of the cuts would be comparable to what an earlier generation of Liberals under Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin implemented at the end of the 1990s to end a generation of deficit spending.

Of course the Liberals are warning against what they call $53 billion in Conservative cuts over 5 years. The number’s not overblown. If Scheer is serious about that 2023-24 target for a balanced budget, he’s going to have to find cumulative savings on that order of magnitude—not absolute cuts, but lower spending than what a Liberal government would have done if it had stayed in office. What Page is saying is that even cuts from projected spending, at that magnitude, are noticed and they don’t feel good.

But for a lot of voters, this is an argument for voting Conservative, not for delaying the effort, because Trudeau has already made it clear that he plans ever-expanding deficits for as long as he’s in office. In 2015 Trudeau asked for permission to run $10 billion deficits, fading to zero before now. He quickly discarded that cap after winning; the deficit this year is about $15 billion. Now Trudeau is asking for permission to run a $27 billion deficit next year, and I don’t see why we should expect him to be any more careful about meeting that target. Scott Clark and Peter DeVries, a former deputy minister and budget chief at the Finance department, sounded alarms about the Liberals’ ability to meet their deficit targets because their platform makes one shaky assumption after another.

So if Scheer’s platform sounds like a recipe for hard cuts now, that’s nothing compared to the rigour that will be necessary to bring spending into line with taxation in four or eight years. Here we see the Liberals falling into the terrible habits of the McGuinty-Wynne Liberals in Ontario; when Kathleen Wynne’s government finally reached a balanced budget after years of effort, she promptly dug a big new deficit because some of her campaign staff had bright ideas about outflanking the NDP on the left. In the end Doug Ford won, and while it’s true some Ontarians wouldn’t do that again, a lot would—and many others would as happily back the NDP, because the Liberals inexplicably abandoned the middle of the road. Since that play led to the lowest popular-vote result for the Ontario Liberals since Confederation last year, I’d have thought their federal cousins would regard that result as a cautionary tale, not an instruction manual.

So if you think balancing the budget will be necessary some day, and that in the meantime government shouldn’t be in the business of making it harder, it’s tempting to vote Conservative. The Liberals, on the other hand, have a clear and distinctive policy of their own. It counsels a rather different use of a vote.

Andrew Scheer promises his first act as prime minister would be to scrap the Liberals’ carbon tax. Because the Liberals return most of the revenues from the tax, in provinces that don’t run their own carbon pricing mechanism, in the form of a direct rebate to consumers, the Parliamentary Budget Office estimates the savings of cancelling the scheme would be trivial. The reason for scrapping the carbon tax is obviously ideological: Scheer believes the natural resources that drive prosperity in Alberta deserve unfettered access to the market. So his “real plan” for the climate is a laughable shell game and it’s fair to assume he’ll do as little to implement his plan as the Ontario Conservatives have done to implement their own “replacement” “plan” since they scrapped the Wynne government’s cap-and-trade system last year.

Again, I guess, for some voters the reason to vote Conservative is precisely that they plan to do nothing serious about climate change. Greg Lyle at Innovative Research has done some fascinating new polling on attitudes toward climate change, and he finds that 52 per cent of respondents who believe climate change is “definitely not occurring” are planning to vote Conservative. But that’s a small voter pool; 86 per cent of all respondents in Lyle’s poll believe climate change is “definitely” or “probably” occurring. So Conservative success in this election depends on winning the votes of a few Canadians who think climate change is happening and support efforts to do real things about it. In other words, they need at least a few voters who are confused enough to vote Conservative even though they want to fight climate change.

Lyle’s research suggests they may get that decisive sliver of support. Lyle had his callers read a detailed description of the Trudeau government’s tax-and-rebate policy to respondents. Slide 20 in his deck of results shows that among those who “strongly support” the policy when they hear about it, 9 per cent are planning to vote Conservative nonetheless. And among those who “somewhat support” the Liberal plan, 13 per cent would vote Conservative.

Those are the voters Carol Clemenhagen, the Conservative candidate in Ottawa Centre running against the Liberal incumbent Catherine McKenna, is trying to nail when she puts the words “Climate Action” on some of her lawn signs. The suckers. I’ve been critical, in exhaustive detail, of the shortfalls, contradictions and limitations of Trudeau’s climate-change policy, but the fact is, he has one. And in the last year of his first mandate, he implemented a widespread carbon tax, the first effective carbon emission-reduction mechanism any federal government I’ve covered has introduced. Scheer’s first priority is to scrap that mechanism and go back, listlessly and with no interest or conviction, to the drawing board. That’s the central distinction of this election.

As climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe and economist Andrew Leach have written, “No matter how you slice it, the Liberals have implemented this country’s first serious, national climate change plan, and they’re looking to build on it.” That the Liberals have done nearly nothing to indicate how they’d build on their plan is maddening, but the stakes are this: keep what they’ve done so far or scrap it.

It would be nice to have a government that takes fiscal responsibility and climate action seriously. It would be nice if Trudeau had not surrounded himself with people who measure their own virtue by the billions they toss into untested and probably counterproductive programs, or if Scheer had any real interest in climate action. But this year you have to choose. And if, like a great many Canadians, you believe the climate crisis can no longer wait, while the fiscal crisis is not yet urgent, then the choice is clear.